The past decade has witnessed a greater awareness amongst historians of late medieval and early modern Ireland of the importance of bardic poetry in the analysis of intellectual trends amongst the Gaelic elite. The estimated total of some 2,000 extant poems constitutes the most extensive body of evidence left to historians by the Gaelic polity.

Functional and public in form and aim

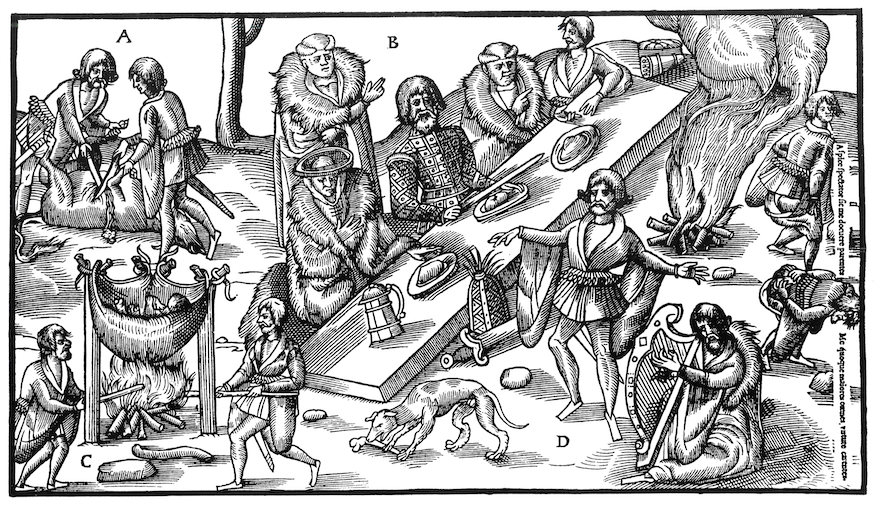

Unlike modern verse the bardic material was not the product of individual literary inspiration, but functional and public in form and aim. Between 1250 and 1650, bardic poets (filí) composed in a style characterised by strict syllabic metres and formulaic conceits and imagery, which were conceived within an institutional framework of bardic education and aristocratic patronage. The poems, composed in the standardised literary dialect called Classical Irish, are invariably addressed to important figures: ruling or aspiring lords and members of noble families.

A bardic web of patronage and activity extended throughout the Gaelic world, from the Hebrides in the north to Cape Clear in the south. Even if a poem praised the stewardship of the most minor of lords, the language and conventions employed were intelligible throughout the Gaelic world. As the recipients of a common and rigorous bardic training, the poets were mobile interpreters of an established body of political and cultural assumptions. It is the universality of bardic material combined with the prolonged cogency of their imagery which makes the poetry a fascinating, if at first sight, intractable historical source.

Two types: duanairí and composite collections

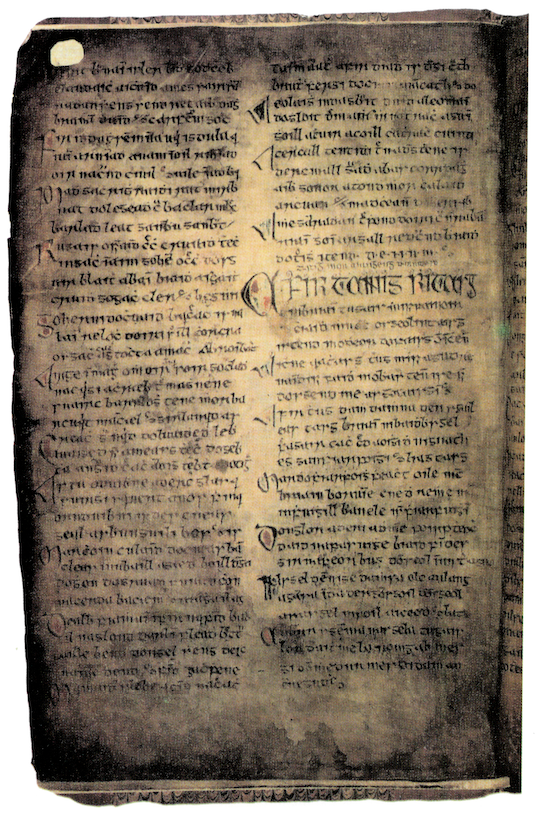

While the majority of poems are addressed to individual members of the Gaelic élite, a significant minority are devotional pieces, love poems, and various miscellaneous compositions in the bardic style. The main source for poems addressed to potentates is that of the duanairí (poem-books), a patron’s personal collection of poems. These poems are usually traditional in tone, since their objective was to glorify the activities of the addressee. However poems from early modern duanairí often provide evidence of bardic reaction to change. Many informative pieces are preserved in composite or general manuscript collections. Three composite manuscript collections put together on the continent in the early seventeenth century (The Book of O’Donnell’s Daughter [c.1613?-?]; The Book of O’Conor Don [1626-31]; and the O’Gara manuscript [c.1655-59]) constitute a particularly rich source for historians of early modern mentalities.

It is important that the poems are distinguished by their source of preservation. Since by their nature the duanairí served as the focus for poems dealing with the ambitions of a specific lord, the picture delineated can be decidedly traditional and limited: the political position of the dedicatee is highlighted at the expense of a wider ideological picture. On the other hand, a piece dealing with a non-formulaic subject, such as social and political upheaval in Jacobean Ireland, will have been more readily conserved in a composite manuscript containing a variety of different types of bardic poem. It is necessary, therefore, to balance the account yielded by duanairí with that of more independent and spontaneous compositions.

Practical political role

Examination of poetry preserved in the duanairí quickly reveals the motivating function of the bardic apparatus: legitimisation. This discourse was not only aesthetic but also assumed a practical political role. When a patron employed the services of his court poet or a visiting file, he was at once acknowledging tradition and making a statement about his self-perception and status in Gaelic society. Using the formulaic stock of motifs, the poet located his patron’s supposed virtues and traits within the ideological and social boundaries of aristocratic society. Conventional characteristics such as bravery, generosity, learning and personal beauty fitted him into the conventional mould of lordship. While the poet composed for the lord, he also directed his work to the larger audience of the polity. In its crudest embodiment, the bardic poem was an essay in self-aggrandising propaganda, purchased by the patron in a public effort to establish or bolster his social and political credentials. This functionality of the genre needs to be kept in mind by historians, both in the selection of source-material, whether from the duanairí or composite manuscripts, and their subsequent reading of the evidence.

Dominated by the manuscript

Bardic poems are preserved in a wide variety of manuscripts dating from the late medieval period through to items copied by scribes and antiquarians as late as the nineteenth century. In the absence, due to adverse social and political conditions, of a significant number of printed books in Irish, the dissemination and transmission of Gaelic literature was dominated by the manuscript. Relatively large numbers of manuscripts, containing a range of material in prose and poetry, circulated amongst the literati both prior to the consolidation of English power in the reign of James I and up to the nineteenth century. This cultural patrimony was oral and literary in so far as a core intellectual élite of littérateurs and scribes conserved and transmitted manuscript material for a limited readership and a considerably wider audience of listeners. For contemporary historians the interpretation of bardic poetry presents problems stemming from its unique and sophisticated niche in Gaelic society, and also from the immediate problem of difficult direct linguistic access. Even for those with a competent reading knowledge of modern Irish, the language of the poems presents problems of interpretation and translation.

Bradshaw and Dunne: two schools of thought

The complexity of the historical interpretation of bardic poetry and the valuable results to be yielded are evident in the debate over the past decade about the historical potential of bardic poetry. This historiographical controversy was initiated by the appearance in 1978 of an interpretative article by Brendan Bradshaw on the sixteenth and early seventeenth-century material in the poem-book of the O’Byrnes of Gabhal Raghnuil. He argued that these poems presented evidence of the dynamism of the Gaelic response to conquest. Crucially, he made the case that these poems revealed their authors to have been capable of adopting a national political perspective rather than one essentially local in scope. Moreover, he claimed that the poems also demonstrated a sense of national consciousness vis-a-vis expansionary English authority. The intellectual outline of this debate was established with the publication of Tom Dunne’s study of the Gaelic response to conquest and colonisation in early modern Ireland (Studia Hibernica 20 [1980]). Dunne argued that the literati, and by extension the Gaelic élite, were uncomprehending and intellectually passive in their response to social and political flux, confronting a rapidly changing world with antiquated conventions. He recognised no trace of a national perspective in the material.

Bradshaw and Dunne respectively have set the pattern for subsequent contributions to the debate, distinguished by several forcefully argued contributions; neither interpretation can yet be said to have gained canonical acceptance amongst historians. That the debate has continued for some sixteen years may be attributed to the relatively large amount of poetry to be considered and to its interpretative difficulties. However, several themes which shed light on Gaelic mentalities in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries have been brought into focus: the association of faith and fatherland, the rapprochement between the Gaelic and Old English élites, a heightened sense of ethnicity, the invocation of divine providence to account for group misfortune and the militant implications of the prevalent comparison of the Gaelic Irish with the Israelites in their Egyptian bondage. The presence of such themes in the poetry supports the reading of the material which stresses its positive and politically-adept qualities. The intellectual utility of the genre as an historical source is now acknowledged and further research is sure to yield valuable insights into the intellectual and cultural history of the Gaelic and gaelicised Old English élites.

The second part of this essay illustrates the types of world-view evident in bardic poetry. Drawing upon poems composed in the second half of the sixteenth-century for Philip O’Reilly (d. 1596) of East Bréifne and a poem addressed to the MacWilliam Burke (d. 1580), it is apparent that the poetry is characterised by two levels of discourse: one traditional in outlook and the other dynamic in emphasis.

Philip O’Reilly of East Bréifne

The poems for Philip were composed against a background of change both nationally and locally in East Bréifne. Although Philip’s anglicised elder brother had succeeded to the O’Reilly lordship with English support upon the death of their father in 1583, the traditional concept of the lordship was soon altered. The new lord, John, and other leading O’Reillys accepted a plan for territorial reform sponsored by the lord deputy Sir John Perrot. The essence of this agreement was the abolition of the O’Reilly lordship and the division of its lands amongst a handful of leading O’Reillys, including the politically-ambitious Philip. The latter’s intemperate behaviour at the 1585 Dublin parliament resulted in his detention at Dublin Castle, where he was to remain until 1592. With the help of the Earl of Tyrone, Philip secured the traditional title of O’Reilly in 1596, a long-sought objective which he held briefly until his murder in the same year.

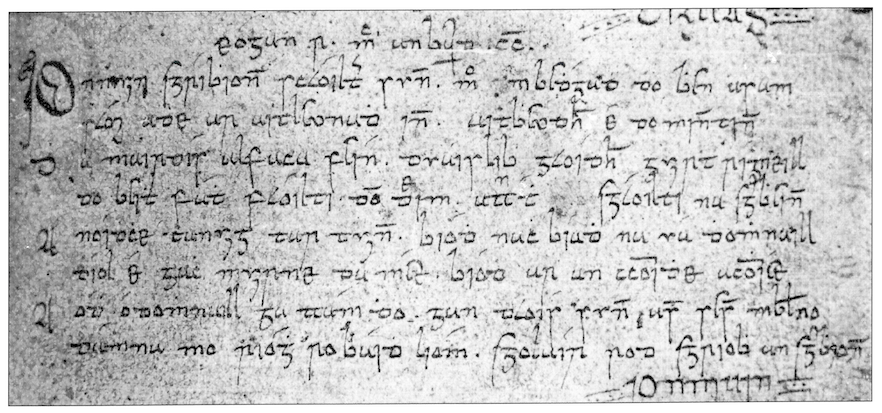

Some poems mediated orally

The poetry composed for Philip provides extended confirmation of his dynastic ambitions, and yet often reflects the influences of a broader political scenario. While there is a contemporary reference to Philip’s duanaire, all the poems addressed to him in University Library of Cambridge MS 3082 were written down by four different scribes at various dates between the last years of the sixteenth century and the final entries in 1639. Although the poems were composed for Philip during his lifetime or on the occasion of his murder, they were entered into this manuscript after his death. This fact serves to underline the continued potency of the poetry subsequent to its composition and actual delivery. One scribe, who in 1620 copied material into the manuscript at the behest of Philip’s son Maol Mórdha, states in a marginal note that he wrote down the poems from the recitation of a blind old man who had committed them to memory thirty years previously. A remark by the scribe in the same note that he would like to see Maol Mórdha become lord of Bréifne suggests that the latter’s interest in his father’s poetry was not merely sentimental, but may also have been political in motivation. The oral conservation of these poems reminds us that for a large element of early modern Gaelic society their contact with the literati would have been mediated orally. This non-literate factor widened considerably the potential influence of bardic practice.

Bardic strategies for legitimisation of the political ambitions of the dedicatee are concisely summed up in two aphorisms from Philip’s collection. At one point, it is remarked of Philip that he clearly understood that fame outlives a lifetime (maith do thuig sé an seanfhocal gur buaine bladh ná saoghal: J. Carney (ed.), Poems on the O’Reillys [Dublin 1950], 11.1107-8). On another occasion, Philip was advised to emulate past lords, implicitly suggesting that adherence to tradition would guarantee his standing within the social structure (ná bí acht do réir na ríogh reamhuibh: ibid., 1.2415). These maxims illustrate the significance of reputation and pseudo-historical precedence in the bardic process of legitimisation. Philip’s seigneurial potential is established by his comparison with ancient heroes (e.g. Fionn, Aodh Eanghach), the presentation of the genealogical merits of his case, his possession of such physical attributes as bravery, generosity and personal beauty. Since the poets effectively issued the intellectual imprimatur of lordship, it hardly needs emphasising that some of their number must have had a potentially influential political role in élite circles.

Fearghal Óg Mac an Bhaird

Again using the evidence of the poems addressed to Philip, it is clear that the bardic paradigm was capable of maintaining discourse at more than one level. The poets might manipulate convention to adumbrate ideas not necessarily related to the endorsement of the ambitions of the addressee. A poem by Fearghal Óg Mac an Bhaird (no.XIX in Carney), a prominent northern poet active in both the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods, is a striking assertion of the geographical and cultural integrity of the island of Ireland. Ostensibly conceived as a panegyric for Philip, the sustained national scope of the poet’s referential framework suggests that he was using the poem for Philip to promulgate a message to a larger audience. In the first stanza he declares help to be at hand for Ireland, thus immediately setting a scene where the island faces an unspecified threat or adversary. He speaks of Ireland’s depression and states that it is Philip, thanks to his martial prowess, who will play a part in ensuring that her sorrow is temporary. In an almost baroque series of stanzas, he highlights those qualities of Philip’s which will serve to aid an Ireland in distress, claiming that O’Reilly will halt the foreign invaders. In this instance, Mac an Bhaird has subverted bardic convention and employed a standard praise poem to draw attention to wider issues of ethnicity and contemporary national politics.

Lochluinn Ó Dálaigh

A similar duality of expression and intention is evident in a poem composed by Lochluinn Ó Dálaigh to lament Philip’s murder by a group of O’Neills in 1596 (no.XI in Carney). A typical bardic elegy in so far as the subject’s public virtues are alluded to and praised, yet the poet manipulates his medium to comment on national political questions. The immediate violence of O’Reilly’s demise provides an opportunity for an oblique commentary on the state of Ireland. If Philip has fallen victim to the treachery of fate, his passing, argues the poet, is a precursor of the advent of English sovereignty, which he finds ironic since Philip died at the hands of his fellow Irishmen. He expresses fear for those who have not understood that Philip’s death is not merely local in significance, but a contributory factor to the external domination of the men of both Ulster and Connacht. His passing endangers the whole of Ireland, for had he lived the English would have been contained, now the doors of danger lie open. This poem is likewise binary in function; at one level the poet commemorates Philip, while at another he points to the necessity for unity amongst the Gaoidhil in the face of an external threat. Again, he uses a conventional medium to provide a national political commentary.

Tadhg Dall Ó hUiginn and the MacWilliam Burke

A poem composed by Tadhg Dall Ó hUiginn (d. 1591), probably dating from the late 1570s, for the MacWilliam Burke (d. 1580), a descendant of the Anglo-Norman de Burgo family, provides fascinating evidence of a Gaelic intellectual outlining a symbiosis of differing ethnic identities (E. Knott (ed.), The Bardic Poems of Tadhg Dall Ó Huiginn (London 1922), no.17). While the greater part of the poem is devoted to a conventional eulogy of the subject and his ancestors, he also re–evaluates the exclusivity of the Gaelic racial paradigm. Working from the premise that force of arms legitimises the conquests of incoming peoples, he observes that the country had been held by a series of different peoples, the Gaelic Irish who had succeeded several groups were in turn joined by the Anglo–Normans. Therefore, the poet demands, rhetorically, if any of the Gaoidhil, themselves former newcomers, could doubt the legitimacy of the presence of the Burkes in Ireland. He declares the family to be of the country. This poem is an important piece of evidence in the analysis of the development of concepts of Irish nationality and indicates that bardic poets manipulated tradition to provide a reading of contemporary events which was positive in outlook.

Conclusion

While acknowledging the apparent conservatism of reference evident in the poetry, it should be stressed that the bardic outlook was sufficiently resourceful to make provision for alternative strategies to cope with topical events. Therefore, it is not correct to assume that the bardic paradigm was antiquated or merely local in focus. In fact, the contrary holds, for careful examination of the material reveals the bardic discourse to have been capable of assessing a variety of issues within the supposed confines of tradition. Bardic poetry offers many valuable insights into Gaelic mentalities and therefore must be reckoned as an essential source for the evaluation of the intellectual history of early modern Ireland.

Marc Caball works for the Ireland Literature Exchange, Dublin.

Further reading:

B. Bradshaw, ‘Native reaction to the westward enterprise: a case-study in Gaelic ideology’, in K.R. Andrews et al (eds.), The Westward Enterprise: English Activities in Ireland, the Atlantic and America 1480-1650 (Liverpool 1978).

P.A. Breatnach, ‘The Chief’s Poet’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 83C (1983).

K. Simms, ‘Bardic Poetry as a Historical Source’, in Dunne (ed.) The Writer as Witness: Literature as Historical Evidence (Cork 1987).

M. Caball, ‘Notes on an Elizabethan Kerry bardic family’, in Ériu XLIII (1992).