By Felix Larkin

Dublin Opinion, the self-styled ‘national humorous journal of Ireland’, was published monthly between 1922 and 1968. It was a miscellany of quips, short articles, poems and cartoons—all in a humorous vein, but with serious intent. The journal, without sacrificing its humour, always had the capacity to convey a serious message—and the message had greater impact because it was delivered in a humorous way. It saw humour as an inherently serious matter: to quote C.E. Kelly, one of its editors and its most talented cartoonist, ‘true humour is not idle words … but has a useful function as a corrective of folly, pomposity and injustice’. Accordingly, the editors of Dublin Opinion would claim ‘that humour is the safety valve of a nation, and that a nation which has its values right will always be able to laugh at itself’.

C.E. KELLY AND ARTHUR BOOTH

Kelly is the person most associated with Dublin Opinion, but the credit for establishing the journal must go to Arthur Booth, who financed the first issue with the help of a loan from a friend. Booth was its first editor. Kelly was on board from the very first issue. Both men—Booth and Kelly—were Dubliners, and both were gifted cartoonists. They were aged 30 and 19 respectively when they embarked on their unlikely publishing venture. Booth was a clerk in the Dublin United Tramways Company, and Kelly a junior civil servant in the Office of National Education (precursor of the Department of Education). They had met through an amateur dramatic society in Dublin. They soon recruited a work colleague of Kelly’s, Tom Collins—also a Dubliner, aged 28 in 1922—as the main writer; Booth and Kelly would contribute mainly cartoons. When Booth died prematurely of tuberculosis in 1926, Kelly and Collins became joint editors of the journal, and they continued in this partnership for the next 42 years. Collins retired from the civil service in 1934 to work full-time on Dublin Opinion. Kelly remained a civil servant and enjoyed a conspicuously successful career, becoming director of broadcasting for Raidió Éireann (then part of the Department of Posts and Telegraphs) from 1948 to 1952 and later director of savings in charge of the Post Office Savings Bank.

ACCUSATIONS OF BIAS

It was quite bizarre for a serving civil servant, and a senior one to boot, to be running a publication like Dublin Opinion. Kelly’s dual roles did sometimes give rise to adverse comment, if not controversy. One such occasion was in 1948. Fianna Fáil had been defeated in the general election in February of that year, and some party members took exception to the July issue of Dublin Opinion. It was, admittedly, favourable towards the new government, and one cartoon conveyed the hope that the government’s initial good fortune would continue. It showed the ministers all superstitiously touching the cabinet table, with the caption: ‘The government, feeling that things are going with an almost alarming smoothness, touches wood’. The matter was raised in the Dáil by two former Fianna Fáil ministers, Seán MacEntee and P.J. Little—and Little had been minister for posts and telegraphs in the outgoing government and therefore Kelly’s political boss. While MacEntee described Dublin Opinion as ‘a certain party political journal published monthly in this country which has been consistently anti-Fianna Fáil’, Little complained that ‘a permanent official is running a monthly magazine which has taken sides in politics with considerable emphasis’. He continued: ‘There were times when I was in office when that complaint was made and, by disciplinary action, we tried to control it, but I feel now … the Minister will have to take very grave notice of the completely partisan attitude taken up in that paper’. The minister, James Everett, defended Kelly, and his career was not adversely affected.

More usually, however, Irish politicians were as amused as everyone else by the fare on offer in Dublin Opinion, and most recognised its value in reducing the deep-seated tensions in Irish public life in the aftermath of the Civil War. Moreover, Dublin Opinion’s approach was, in Kelly’s own words, to give only ‘kindly criticism’—by which means, he said, ‘we made no enemies and our victims became our friends’. He noted that ‘our general policy was that, where we did criticise, we should do so without inflicting pain, and that the successful critical cartoon or article was one which made the victim (if there was one) laugh’.

Dublin Opinion was ‘one of the most political funny papers in existence’—that’s the verdict of Vivian Mercier in a short study of the journal published in The Bell in 1944. Its political bias has been aptly described as ‘generally on the side of the people and following our national propensity for being humorously “agin” whatever government may be in power’. It claimed not to have any politics, by which it meant no party politics, and it never, for example, endorsed or opposed any party or candidate at election time. Its political manifesto, set out in an early issue, makes it abundantly clear where it stood and what its priorities were:

‘Our politics—we have none. It is our duty to support the Free State, because it is here, for good or ill, by the wish of the people. Against the principle of the Republicans there is nothing to be said. Principle is written in letters of gold, proof against the acids of logic and sophistry. And so, if in these pages we poke a little fun or make a weak jest at the expense of men of various political views, we mean it in the spirit that will be theirs again—the spirit of camaraderie—the spirit that is so necessary, particularly between men who have been comrades in arms.’

In short, its view was that, since the majority of the Irish people had accepted the Free State, the politicians should now get on with the job of government in a spirit of co-operation in the best interests of the people. The pursuit of greater independence could wait for another day.

Despite Dublin Opinion’s support for the Irish Free State—and contrary to MacEntee’s claim in 1948 that it was less than sympathetic towards Fianna Fáil—Dublin Opinion maintained a reasonable degree of impartiality throughout its 46 years of publication. It is likely that the issue of which MacEntee complained simply reflected that Dublin Opinion had grown weary of Fianna Fáil after sixteen years continuously in government and welcomed a change.

Vivian Mercier, in his study of Dublin Opinion in The Bell, explains its impartiality as follows:

‘The real secret of Dublin Opinion’s impartiality, I believe, is that its sympathies were with the losing side [in the Civil War]. It could not attack those in power, who then had the majority of the people behind them. At least, it could not if it wished to keep its circulation, or even, perhaps, some freedom of speech. On the other hand, it had no desire to persecute the unhappy Republicans.’

In confirmation of his analysis, Mercier notes that Dublin Opinion ‘has succeeded in drawing its readers from men of all parties’—a remarkable achievement in an era when Civil War divisions in Ireland were still very raw.

EMMETT’S UNWRITTEN EPITAPH

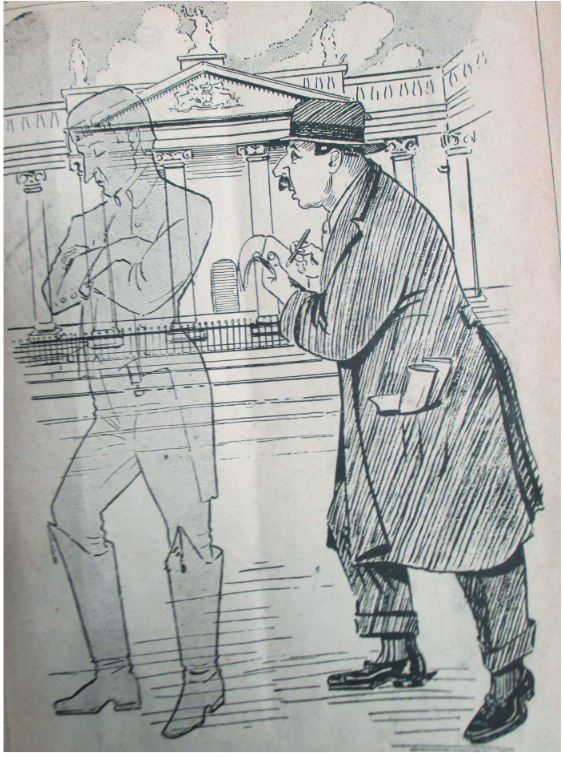

This is the background to a remarkable series of four cartoons that appeared in Dublin Opinion using the ghost of Robert Emmet and the unfinished business of his unwritten epitaph—a potent appeal to Irish emotions. In his famous speech from the dock in 1803, Emmet had said: ‘When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written’. Thus, in its very first issue in March 1922, just after the Anglo-Irish Treaty had been ratified by the Dáil, Dublin Opinion published a cartoon in which a reporter asks the ghost of Robert Emmet whether his epitaph might now be written (p. 36). The reply is an emphatic ‘Not yet’. Clearly, while supporting ‘the Free State, because it is here, for good or ill, by the wish of the people’, Dublin Opinion recognised that it fell short of the republican ideal—but ‘against the principle of the Republicans there is nothing to be said’.

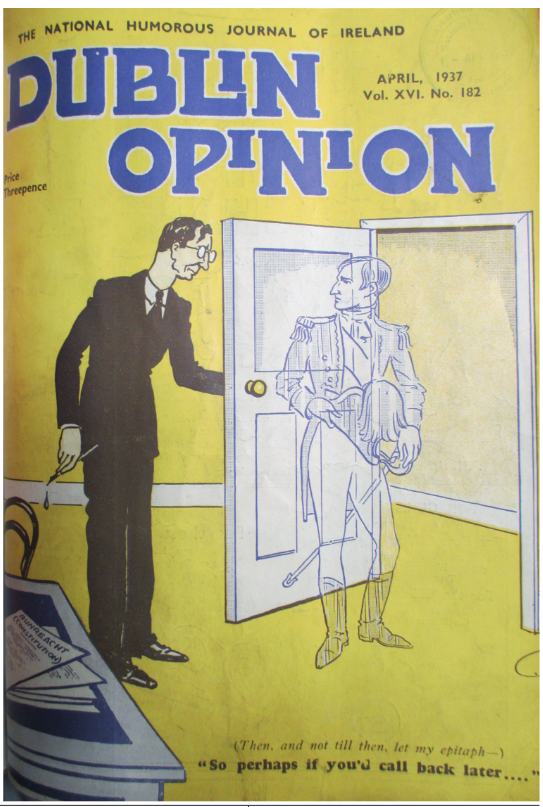

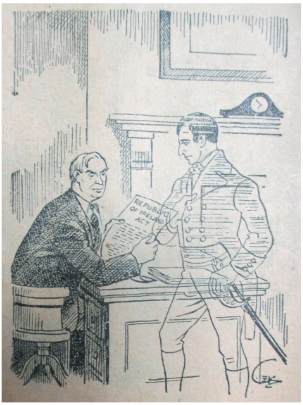

In 1937, with de Valera’s new constitution imminent, Emmet’s ghost reappears—somewhat expectantly—on the cover of Dublin Opinion, but is told by de Valera to ‘call back later’ (p. 37). There is still unfinished business before his epitaph may be written. Predictably, the matter comes up again when Ireland was formally declared a republic in 1949. A cartoon in the December 1948 issue shows Emmet’s ghost anticipating the declaration and saying to the taoiseach, John A. Costello, ‘One more step, Mr Costello, and then let my epitaph be written’ (p. 38, top). The republican ideal was about to be realised—and by peaceful means—and Dublin Opinion rejoiced in that.

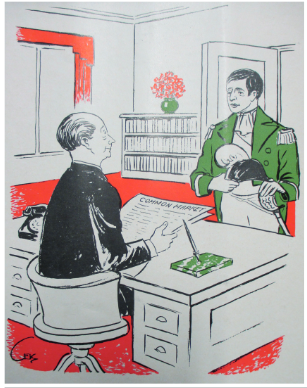

Curiously, the theme of Emmet and his epitaph is given a new twist in the issue of Dublin Opinion of July 1967. The then taoiseach, Jack Lynch, was embarking on Ireland’s second application to join the EEC (still comprising six member states) but he is confronted by Emmet’s ghost, who tells him: ‘When my country takes its place among the nations of the Six, then, and not till then, let her epitaph be written’ (p. 38, bottom)—not exactly an endorsement of the aspiration to join the EEC!

This warning about the danger of a loss of sovereignty—compromising the republican ideal—would be Emmet’s last appearance in Dublin Opinion. In the 1960s its circulation, which had remained constant at over 40,000 per issue since 1925, began to decline. The politicians whom it had lampooned so brilliantly since 1922 were growing old and passing from the scene, and it simply did not have the measure of the next generation then emerging to claim power. Moreover, its humour now seemed very timid compared to the vicious satire in, for example, the British magazine Private Eye and the BBC television programme That was the week that was. Their sallies against the great and the good could be both personal and offensive, in contrast to the gentle humour of Dublin Opinion. Kelly and Collins sold up in 1968, though the journal struggled on under new ownership for a brief period afterwards—a pale shadow of its former self.

Felix M. Larkin is a historian and former public servant.

Further reading

C.E. Kelly, ‘Dublin Opinion, 1922–1968’, Irish Press, 15 October 1970.

F.M. Larkin, ‘Humour is the safety valve of a nation: Dublin Opinion, 1922–68’, in M. O’Brien & F.M. Larkin, Periodicals and journalism in twentieth-century Ireland: writing against the grain (Dublin, 2014).

V. Mercier, ‘Dublin Opinion’s six jokes’, The Bell 9 (3) (December 1944).