By John Bergin

Catholics of the early modern era in Ireland and in England have often been considered as quite distinct and unconnected. In fact there were links, not least at the level of the landed gentry, who crossed the Irish Sea in both directions, settling, intermarrying and owning property in each other’s countries. The Tasburghs, a Catholic family from Suffolk and Norfolk, had considerable Irish interests from the early seventeenth century to the middle of the eighteenth century.

CRESSYS AND TASBURGHS

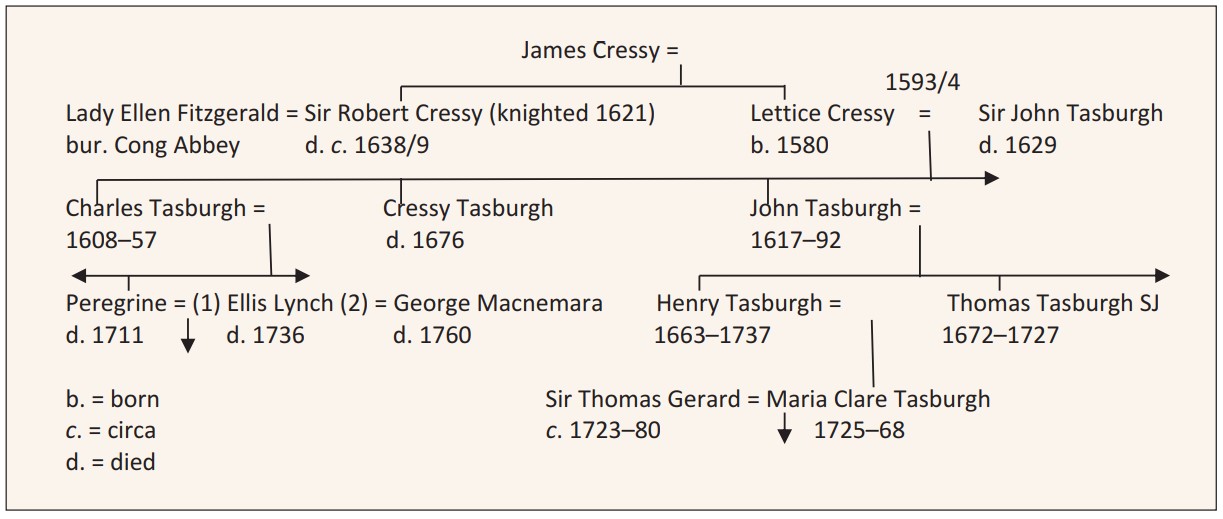

In 1611 the lands of the dissolved abbey at Cong in County Mayo were bought by Robert Cressy of London, who, with his nephew Cressy Tasburgh, ‘held and enjoyed the said lands and premises until the wars of 1641 [and] immediately after the wars of ’41 the said Cressy Tasburgh being an English Catholic entered upon and enjoyed the said lands and premises’. Cressy Tasburgh was the second son of Robert’s sister, Lettice Cressy, who was married to Sir John Tasburgh of Flixton in Suffolk. Sir John was a ‘hot Protestant’, but Lettice was a Catholic who, after her husband’s death in 1629, controlled the education of her children.

We do not know whether Robert Cressy lived on his estate, though his Irish widow is said to have been buried in Cong Abbey in 1660. Cressy Tasburgh and his eldest brother—‘cultivated young men with grand social connections’—were educated at Christ’s College, Cambridge, and Gray’s Inn. It seems unlikely that Cressy Tasburgh was a resident landlord, and in 1667 he sold the estate to his brother John, of Bodney in Norfolk. In 1679 John was granted ‘a pass to go with his family into Ireland, there to remain for a year and to follow his lawful occasions, having an estate in Connaught’. He hoped to ‘build at Cong and settle my son there for a lasting habitation’. John died in 1692 and left the Cong estate to his son Henry Tasburgh, who preferred, however, to live in his fine townhouse in London’s Lincoln Inn Fields.

Little is known of the management or letting of the estate before 1695, when Henry appointed his cousin Peregrine Tasburgh as his resident agent in Cong at a salary of £50 a year. From this date there is a good deal of surviving correspondence between the landlords and their agents and head tenants in Ireland, as well as estate accounts and details of the rents remitted to London. Peregrine, already in middle age and apparently a widower when he moved to Cong, promptly married sixteen-year-old Elizabeth Lynch of Lydacan, Co. Galway. Apart from visits to London and Dublin, Peregrine remained at Cong for the rest of his life. He became head tenant in 1702 and died in 1711, to be succeeded by his widow Elizabeth, usually called Ellis.

Ellis went to London after Peregrine’s death and negotiated her own lease with Henry Tasburgh. In 1721 she married a second time, and her lease was superseded the following year when her new husband, George Macnemara, obtained a lease in his own name. But Ellis, even when she was not formally head tenant, was never less than an equal business partner with Peregrine or George. Ellis had no children with George but had three daughters from her first marriage, while George already had several children outside marriage (and would have further children in two later marriages). Ellis died in 1736, and George left an account of her elaborate funeral, which included ‘three tables of cold meat, one for the gentlemen, another for the clergy and the third for the women, that were her relations’.

ABSENTEE LANDLORDS

The absentee Tasburghs in London—even during the Irish residence of Peregrine, their near kinsman and fellow countryman—were rarely satisfied with the management of the estate or the income they received from it. In 1698 Henry travelled from London to Cong, keeping a detailed journal, and spent several weeks on his Irish estate. Henry’s younger brother, Thomas Tasburgh, came to Ireland in 1726 to investigate estate business. Thomas was a Jesuit priest and represented his brother’s interest, but also his own, as he was entitled to an annuity from the estate. In Dublin Thomas met George Macnemara (always late in remitting rents) and told him that ‘since he had starved me in England I was come to try whether I could live in Ireland’.

Thomas left a lively and opinionated journal of his time in Cong and in Dublin, where he died ‘in great repute for sanctity’ in 1727. He was buried at St Michan’s in Dublin and ‘many miracles were performed at the tomb of this Father’, according to Jesuit tradition.

GEORGE MACNEMARA, ‘PRINCE OF CONG’

While the Tasburghs’ Irish involvements were forgotten until recently, their last head tenant, George Macnemara, lived on in Cong tradition. Several accounts of his life and deeds have been published, and the versions of folklore and literature prove to have some basis in the historical Macnemara. He was an extravagant, even bombastic, character, and was once called ‘Prince of Cong’, while Thomas Tasburgh thought him ‘a bully blusterer’. A native of County Clare, George was involved in numerous lawsuits and had several brushes with the criminal law.

After the death of his first wife, Ellis, George remained almost continuously as head tenant at Cong until his death. He lived in some style on the estate and, at times, in Dublin and even London. He was himself related on his mother’s side to the Tasburghs, but they wearied of his slow remittances of rents and his fertile excuses. They never managed to dispense entirely with their wily head tenant and collaborated with him when their interests coincided—principally in resisting the claims of the Protestant clergy to the impropriate tithes, and the claims of another family to the estate. This claim was appealed all the way to the British House of Lords, which ruled in favour of Henry Tasburgh and his co-appellant George Macnemara in 1734, prompting George to write to Henry (with a typical flourish) that ‘poets, bards and musicians have exercised their talents on the subject of our conquest’.

Henry Tasburgh died in 1737 and the last Tasburgh owner of the estate was his only child, Maria Clare. In 1749 she married the Catholic Sir Thomas Gerard, a wealthy Lancashire baronet, and the Cong estate was to be sold as part of her marriage settlement. The estate was eventually bought in 1756 by Stephen Creaghe Butler, brother of George’s second wife and a convert to the Church of Ireland, but in trust for George, who died at Cong in 1760.

PENAL ERA

The Catholic faith of the landlords and their head tenants lends special interest to the history of the Cong Abbey estate. The Tasburghs had been caught up in the Popish Plot trials in England in 1679–80, while Ellis Lynch’s and George Macnemara’s fathers were both officers in King James II’s Irish army in 1689–91. The Tasburghs kept a low profile during the reign of James II and the war in Ireland, and the estate was unscathed by the forfeitures under William of Orange.

Cong Abbey’s landlords and head tenants alike generally lived in comfort and security despite the penal laws. They were, however, keenly aware of their legal disabilities, many relating to landed property, and they employed an array of lawyers to defend their interests. After 1695 Catholics were forbidden to bear arms without a licence from the privy council. George lobbied for such a licence in 1735, writing that ‘other papists carry arms thus and I could attend my markets and fairs, drive far and near and fear nobody, whereas a naked man can do nothing’.

Religious practice is rarely discussed in the sources, though in 1698 Henry Tasburgh visited the Catholic shrine at St Winefride’s Well in Wales on his way to Ireland and visited a ‘miraculous spring’ on his Cong estate. Henry also recorded many small charitable donations to the poor. A few Catholic clergy are mentioned, and not always very respectfully. The abbot of Cong (the title survived, even if the functions were gone) was a tenant of the estate, and the object of legal proceedings by his landlords.

Several figures connected with the estate conformed to the Church of Ireland, including a son-in-law of Ellis, several of George’s children and George’s brother-in-law, Stephen Creaghe Butler. All the key personalities, however, were Catholics (though it was once observed that it was ‘pretty difficult to say of what religion Macnemara is’). Their relations with Protestants were usually civil, and sometimes friendly. Cong Abbey enjoyed substantial tithe income, which the Church of Ireland clergy waged legal battles to recover. The fact that the tithes were enjoyed by Catholic landlords probably sharpened the resentment felt by ‘the parsons’, as they are called in the estate papers. Archbishop Vesey of Tuam was a neighbouring landlord and a grandee who could make his power felt: he had Peregrine imprisoned in 1695 for breach of privilege of the House of Lords. Peregrine for his part fumed about ‘his Ungrashes the Bishop of Tuam’, while Ellis wrote of the ‘pretended spiritual court’ of the Church of Ireland.

CONCLUSION

The Cong Abbey estate papers were recently discovered in the Lancashire Record Office in the collection of the Gerard family, into which the last of Cong’s Tasburgh owners had married, while Thomas Tasburgh’s journal was discovered in the University of Otago in New Zealand. Together they vividly document the adventures of an English Catholic family in Ireland. They illustrate Catholic society in Connacht, life under the penal laws, and the relations of head tenants and middlemen with both tenantry and landlords. They also demonstrate the decisive role played by one woman in the management of the estate.

John Bergin is an adjunct staff member at UCD School of History.

Further reading

B. Clesham, George Macnemara of Cong: folklore and facts, 1722–1760 (Cong, 2020).

B. Clesham, E. King & J. Bergin (eds), ‘Cong Abbey Estate Papers (1608–1756) and the Catholic families of Tasburgh, Lynch and Macnemara’, Archivium Hibernicum 73 (2020).

Read More: