By Gerard Ronan

Irish troops have been involved in UN peacekeeping activities in the Middle East since 1958, when they were first deployed to the Lebanon–Syria border. However, they were neither the first Irish military presence nor the first Irish personnel to be entrusted with a peacekeeping role in the region. During the previous century, a certain Eugene ‘Hassan Bey’ O’Reilly, whose name had already become something of a byword for courage and controversy, was sent to Mount Lebanon in command of a Turkish army tasked with restoring order in the aftermath of the Damascus Massacre of 1860. Within months he was holding the reins of civil and military power in the region, albeit on a temporary basis.

BACKGROUND

Born in Dublin in 1828, the son of a prominent Catholic solicitor, O’Reilly was educated at Clongowes Wood and later at Trinity College, Dublin, where he sabotaged his path to a legal career by refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy. Estranged from his father and cut off financially, he was forced to seek military employment on the Continent, enlisting briefly in the Austrian army, only to be dismissed for duelling with a fellow officer, allegedly over a woman. Returning to Ireland, he became involved in radical politics as a supporter of John Mitchel and, while still a teenager, became so prominent in the movement that he was invited to be part of the Young Ireland delegation to the new provisional government in Paris that had been formed following a popular uprising and the abdication of King Louis Philippe in February 1848, and asked to remain in Paris to study the art of barricade-building that had proved so successful against the Crown forces in the February Revolution.

YOUNG IRELAND REBELLION OF 1848

During the subsequent rebellion in Ireland, O’Reilly became famous as the youthful leader and organiser of the notorious ‘Blanchardstown Affair’—a paramilitary operation aimed at taking the police barracks at Blanchardstown, confiscating the weapons and then marching on Navan. The operation had to be abandoned when most of the promised volunteers failed to turn up—inhibited, it was said, by the involvement of one P.J. Barry, believed by many to be a Castle spy.

Betrayed to the authorities by a father anxious to see his son’s life spared, O’Reilly was subsequently arrested and imprisoned in Kilmainham, and more latterly in Belfast, only to be controversially set at large after some powerful lobbying by his father, who at the time was attorney to Sir William Somerville, chief secretary for Ireland. Though nominally subordinate to the lord lieutenant, in practice the chief secretary was responsible for the day-to-day governance of Ireland. Somerville’s influence was pivotal in seeing O’Reilly released, and extraordinarily biased press reporting, portraying the youngster as an innocent dupe, helped to repair the damage that had been done to his father’s reputation.

Following his release, O’Reilly fled the country and found employment as a cavalry officer in the Hungarian and Sardinian armies during their wars of independence. In 1851 he returned to England and attempted to enlist in the 10th Hussars, then based at Maidstone, the home barracks of all cavalry regiments stationed in India and where cavalry recruits were sent to be trained. Despite his political connections and his battlefield promotion to lieutenant, the British army refused to recognise his Sardinian rank and he was forced to enlist as a private, the lowest rank possible.

RUSSIA VS TURKEY

The Russians at this time were attempting to expand their influence over the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean at the expense of the declining Ottoman Empire. Britain, France and Sardinia, viewing this as a danger to their respective trade routes, formed an alliance with Turkey to stop them. Commissions were now going a-begging in Turkey, with instant promotions of at least one step in rank available to suitable European recruits. For O’Reilly, recognition of his Sardinian rank of lieutenant would mean an instant promotion to major. It was an opportunity too good to be scorned.

The Turks, however, had a long and decidedly mixed experience with foreign mercenaries. They would not accept just anyone. And so, on 13 September 1853, O’Reilly travelled from Maidstone to Belvedere, joined the local masonic lodge and proceeded immediately to London to take up a long-standing invitation from Lord Palmerston, now the British home secretary, to meet in person. Reminding Palmerston of the military intelligence that he had provided from Sardinia, O’Reilly sought a letter of recommendation for a commission in the Turkish army, expressing the hope that his small part in the 1848 rebellion would not prove an insurmountable impediment to his service abroad. ‘Not at all, my dear fellow’, Palmerston is reputed to have replied. ‘On the contrary, it is one of your strongest recommendations. Anyone having the temerity to embark on an enterprise so desperate has just the sort of mettle we require in the current war.’

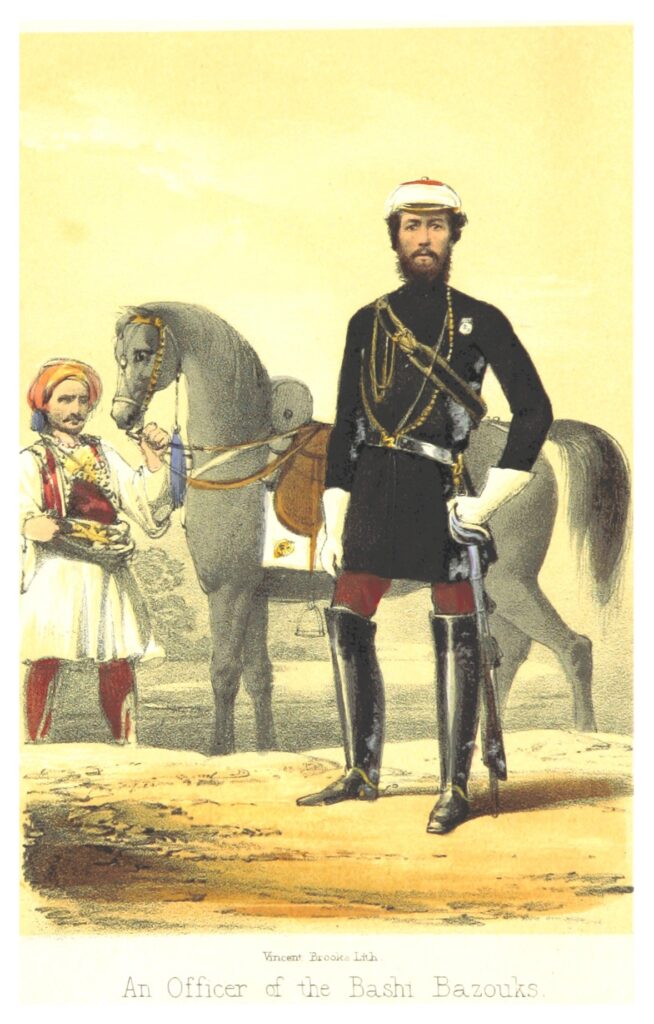

BIMBASHI OF BASHI-BAZOUKS

Extraordinarily for a former Irish rebel, O’Reilly set off for Turkey armed with a recommendation from the British home secretary, whose illegitimate son he would later be rumoured to be. Appointed to the rank of bimbashi, or major, in the Turkish cavalry, he was dispatched almost immediately to Ottoman Bosnia, where he was soon being fêted in the British press as the first Christian to be given a battlefield commission in the Ottoman army, in which he now served under the Turkish name of Hassan Bey. Over the course of the following year there ensued a series of miraculous escapes during his cavalry encounters with Russian Cossacks, the most widely reported of which being the occasion when a Russian cannon-ball passed under his bridle and took off his horse’s head but left him largely unscathed.

O’Reilly’s success in commanding a Turkish regiment of Bashi-Bazouks—an irregular cavalry unit of wild and undisciplined tribal horsemen—led to his being head-hunted to recruit and train a similar unit for the British army, much to the chagrin of freshly commissioned officers whom he now outranked courtesy of yet another step in rank to lieutenant colonel. During this service he effectively ended the military careers of Major-General William Beatson and the explorer Richard Burton by betraying their plans to organise a mutiny. His actions were controversial but were defended in parliament by Palmerston, who by this time had become prime minister.

FROM MILITARY TO PUBLIC SERVICE

After the Crimean War, O’Reilly returned to Turkey, where he was allowed to resume his military career and work his way through the ranks from lieutenant colonel to colonel. Later, thanks largely to his fluency in Turkish, Italian, French and English, he moved from military to public service, first as a translator within the translation service and then as aide-de-camp to the Turkish foreign minister, Fuad Pasha, all the while retaining his military rank.

O’Reilly’s rapid promotion and his adoption of a Turkish name inevitably fuelled rumours at home that he had converted to Islam. It also triggered a smear campaign against him and a widely circulated but provably false allegation that he had led a Sardinian army to a comprehensive victory over an Irish division of the papal army. His reputation was redeemed, briefly, following the Damascus Massacre of 1860, during which several thousand Christians were killed by Muslim rioters. Appointed by Fuad to a judicial tribunal that would later be recognised as the precursor of the International Criminal Court, O’Reilly was also placed in command of a small army that Fuad sent into the Mount Lebanon area to secure the peace and rescue displaced Christians. For several months he was tasked with holding the reins of civil and military power in the region, until permanent appointments were made.

When Fuad was recalled to Constantinople following his promotion to the post of grand vizier (prime minister), O’Reilly was left behind in Damascus as aide-de-camp to the newly appointed governor of Syria, Halim Pasha. Political intrigue opposed to his subsequent appointment as the head of a mounted police force in Syria saw him subsequently recalled to Constantinople, promoted to the rank of pasha, gifted three Circassian slave-girls and appointed as head of a government department in charge of railroads. During this period, an open letter that he wrote to his former Young Ireland colleague William Smith O’Brien, criticising his attempts to raise another rebellion in Ireland without international support, destroyed his reputation at home.

FAILED ATTEMPT TO FOMENT A BEDOUIN REBELLION

His career in a cul-de-sac, O’Reilly began to seek opportunities to line his pockets and was soon conspiring with two Egyptian princes and several foreign investors to raise a Bedouin rebellion in the Hauran desert (spanning the present-day borders of Syria and Jordan) by arming them with modern weapons. If successful, such a revolt could lead to the creation of an independent Syria in which he believed he would be generously rewarded; but even if unsuccessful, the unrest would depress the value of the Turkish lira and allow his backers to make a killing on the stock and currency exchanges.

The rebellion, alas, did not go to plan. Internal tribal rivalries and a betrayal by the infamous Jane Digby, then married to the leader of the Mezrab tribe, left him exposed, undefended, and ultimately arrested and imprisoned. Facing the death penalty for treason, he managed to pass to the British ambassador papers suggesting the involvement of his old mentor Fuad Pasha, papers potentially so embarrassing to the sultan that O’Reilly and his co-conspirators were promptly released and deported.

Following his deportation, O’Reilly fled to France, where he set up home with Mathilde Solymassy, a young girl whom he had married in Constantinople in 1867 shortly before his arrest. Settling in Boulogne-sur-Mer, he fathered a daughter, Eugenie, and a son, Henry, and reinvented himself as a railway consultant. Through the influence of friends, he found work in the service of a consortium of British entrepreneurs seeking a concession from the Serbian government to build a railway from Belgrade to Aleksinac. The contract, alas, was awarded to a competing bid and O’Reilly returned to Bordeaux, where his wife, by now aware that their marriage had never been officially registered, was pregnant with their third child. Despite promising to regularise the marriage at the earliest opportunity, O’Reilly had yet to do so when his new employers sent him to Morocco to lead a commercial delegation to the new sultan.

While waiting in Fez for an audience, O’Reilly contracted cholera. Tortured daily by fever, dehydration and bloody diarrhoea, he slowly wasted away. He deserved better, perhaps, than to suffer an undignified bedridden withering. On 29 December 1873, the ‘dashing sabreur of Calafat and Oltenitza’ lost his final battle and was laid to his eternal rest far from friends and family, leaving his wife and children destitute and with no legal standing. The few who had known him personally described him as a ‘gallant colonel’ whose career had been marred by a tendency to be over-sanguine, and yet a man, for all of that, who was extremely likeable. Today his name is largely forgotten.

Gerard Ronan is the author of Shamrock, crown and crescent—the remarkable life of Eugene ‘Hassan Bey’ O’Reilly, 1828–1873 (Staten House, 2024).