Ulster Museum (until January 2024)

By Donal Fallon

On a busy Thursday morning in July, it was clear what had brought many of the visitors to the Ulster Museum. Within its section dedicated to the Northern Irish conflict, ‘The Troubles and Beyond’, several groups of visitors moved around the landmark exhibition, which includes the lid of a dustbin (banged on the street by women to indicate the arrival of security forces into an area), a loyalist mural reimagining Cú Chulainn (‘the ancient defender of Ulster’) and ephemera from the Belfast punk scene. The exhibition perfectly demonstrates the ability of the Ulster Museum to examine contested histories within the context of a society still divided on the question of how to interpret the recent past. There is not one history of Northern Ireland presented here but several.

It’s indicative of the positive change of recent decades that for younger visitors to the Ulster Museum the star attraction is not the gallery exploring the Troubles but a blackboard that sits outside it. A prop from the hit television series Derry Girls, it lists the differences between Catholics and Protestants as the show’s protagonists understood them to be. ‘Catholics go to Bundoran, Protestants go to Newcastle’ and ‘Protestants paint rubbish murals’ are amongst its observations.

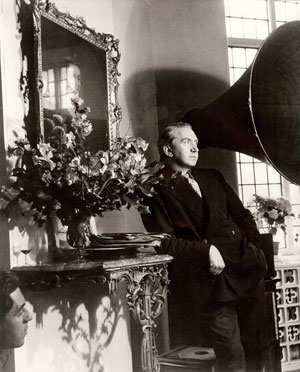

While Derry Girls has captivated millions on the small screen, the Ulster Museum is currently honouring a defining figure of the big screen and Ulster’s cinematic history. Within the Belfast Room, the story of Brian Desmond Hurst is told using lobby cards, Hurst’s own scrapbooks, film posters and archival photographs on loan from the estate of the late director. By exploring Hurst’s career, the exhibition also casts an interesting spotlight on the tensions between popular cinema and art cinema. For Hurst, film was ultimately an art form, which was more important than any commercial interest.

Born in East Belfast’s Ribble Street in 1895, Hurst was the son of a Belfast shipyard worker. His birth certificate lists his name as ‘Hans Moore Hawthorn Hurst’, a name which he would later change. While some shipyard workers were amongst the aristocracy of Belfast labour, this wasn’t the case for Hurst’s blacksmith father; in the very first panel we read in Hurst’s recollections of childhood that ‘I remember once picking up a piece of bread in the street and eating it as I was so hungry’. In the workforce at thirteen and working in a linen factory, he would join the Royal Irish Rifles on the outbreak of the First World War. He was present at Gallipoli, recalling later that ‘Catholic–Protestant division vanished in this holocaust’.

After the war, Hurst embarked on a great journey into the unknown, before an encounter with the director John Ford in the United States transformed the course of his life. From Ford he learned much, and there are some similarities in their output. Much of Hurst’s work would prominently feature the players of the Abbey Theatre, such as Sara Allgood. Like Ford, he presented romantic tales with beautiful Irish scenery. There was Irish Hearts, the first ‘talkie’ made in Ireland, produced in 1934. At the time of its release, Hurst struck a confident note: ‘Ireland in a film sense is one of the best countries in the world. I am surprised the government has done nothing towards the establishment of a film industry in Dublin.’

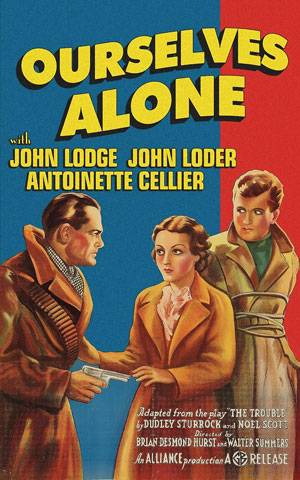

This exhibition will hold significant appeal for those interested in the changing aesthetics and design of cinema posters, presenting vivid posters for a host of Hurst films, some more instantly recalled than others. An especially intriguing poster appears for Ourselves Alone, a 1936 drama set against the backdrop of the Irish revolution. We’re told that, ‘while the film was shown without complaint across the rest of the UK, Minister for Home Affairs Dawson Bates banned the film in Northern Ireland as it was considered Sinn Féin propaganda’. In the Free State the film was condemned in the nationalist press as pro-British! A name that leaps from the poster is ‘John Loder’, otherwise John Lowe. The son of General William Lowe, he had also been present at the surrender of P.H. Pearse in April 1916.

If the Northern Ireland state feared that Hurst was in the business of making Irish nationalist propaganda, they needn’t have worried. Upon the outbreak of the Second World War, we read that ‘his strong support for the war effort … saw him work on a number of propaganda documentary films for the Ministry of Information’. These included A Letter from Ulster, a 35-minute documentary that shows American GIs in Northern Ireland during the war and is screened in the lecture theatre; it was clearly aimed at the American public and presented an image of harmony in Northern Ireland. One of the items illustrated in the display panels is A Pocket Guide to Northern Ireland, given to American soldiers in the region. Soldiers were advised that ‘Every American thinks he knows something about Ireland. But which Ireland? There are two Irelands. The shamrock, St Patrick’s Day, the wearing of the green—these belong to Southern Ireland, now called Éire (Air-a). Éire is neutral in the war.’

Hurst’s great post-war mainstream success was 1951’s Scrooge, which featured Alastair Sim as Ebenezer Scrooge. One of the highest-grossing films of the year in Britain, it was warmly received by the New York Times, who told readers that ‘it does not conceal Dickens’ intimations of human meanness with artificial gloss’. As the film industry changed in the late 1950s, however, Hurst increasingly struggled to produce films that satisfied shifting fashions. His ambitious take on The Playboy of the Western World, with Siobhán McKenna as Pegeen Mike, was a commercial failure.

This exhibition makes good use of its limited space, with cinema posters that pop up in vivid colours. Within its constraints, it chooses to focus on the work over the man. Nevertheless, there are little snippets of biography: we learn that ‘Hurst converted from Protestantism to Catholicism’, and that he ‘was openly bisexual during a time when homosexuality was a criminal offence’. The final section shows us three historical plaques that have been erected to the memory of this fascinating and complex character across the city of Belfast. The last was unveiled jointly by Martin McGuinness and Peter Robinson at Titanic Studios. This exhibition is also a fitting tribute to Hurst, within a museum that does much to highlight the shared histories of Ulster.

Donal Fallon is a historian and the presenter of the Three Castles Burning podcast.