The execution of a National Army officer a century ago followed two shocking killings in rural Kerry in the months after the end of the Civil War.

By Owen O’Shea

The attitude and approach of the National Army and the Free State government to the notorious behaviour of many senior army figures in County Kerry during the Civil War have left an enduring scar on the history of the period. However, the execution in March 1924 of an army lieutenant for the brutal murder of a young civilian in Kerry months after the war had ended, in a killing which exemplified army brutality in the county, represented a shift in official attitudes to army indiscipline and violence after the Civil War.

JEREMIAH GAFFNEY

Jeremiah (Gerald) Gaffney was a particularly vicious, temperamental and volatile soldier who liked to throw his weight around in Kerry during 1923. Born in Dublin in 1900, he was an active member of the Dublin Brigade of the IRA during the War of Independence. In a character reference, his IRA comrades described him as someone ‘who inspired courage, forbearance and a true spirit of patriotism’.

Following the signing of the Treaty, Jeremiah Gaffney, in the words of his mother, ‘marched into Dublin … in his green uniform’ and joined the National Army. With 450 troops on the Lady Wicklow, he landed at Fenit near Tralee on 2 August 1922 as the Civil War intensified. Despite being in his early twenties, he was appointed to the role of lieutenant in the Kerry Command and was posted to Castleisland barracks. The barracks there had a reputation for the particularly brutal treatment of IRA prisoners. It was from there that Lt. Paddy ‘Pats’ O’Connor and four other soldiers were lured to their deaths in an IRA trap mine explosion at Knocknagoshel on 6 March 1923. A few weeks after the killings at Knocknagoshel, Gaffney oversaw the arrest and murder of local man Dan Murphy, at whose forge the mine was allegedly constructed. On Gaffney’s orders, Murphy was summarily executed in a field not far from the site of the explosion.

After the Civil War, Gaffney remained at his post in Castleisland and, according to one of his superiors, ‘he was free to act at his own discretion’. He was known as a hard drinker who oversaw a group of undisciplined soldiers who were known to be particularly aggressive and ruthless.

MURDER OF GARDA SERGEANT JAMES WOODS

On 3 December 1923, Garda Sergeant James Woods was murdered at Scartaglin Garda Station, a short distance from Castleisland, during an armed robbery by local republicans. Woods was the first Garda sergeant killed in the line of duty and his death reopened unhealed Civil War wounds. Even if murder had not been the intention of the raiders, the killing had major consequences for the local community. Gaffney considered the killing of Sgt Woods to be an appalling attack on the Free State itself. He took it upon himself to carry out a series of reprisals, targeting republicans in the area in particular.

Hours after the death of Woods, Gaffney led a raid on the home of the O’Connor family, who were known republicans. The women of the house were viciously assaulted and a young servant boy, Con Horan, was shot, the bullet being removed from his back the following day.

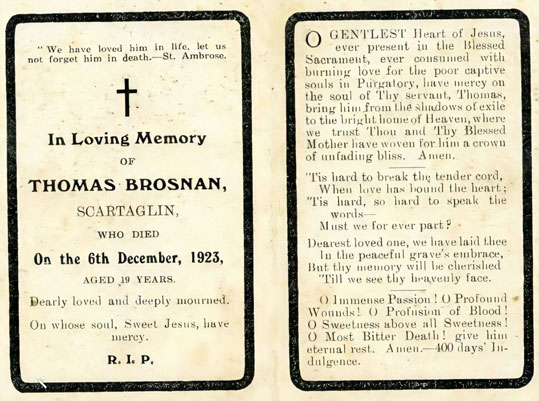

Two days later, Gaffney went drinking in Scartaglin. He sent some of his men to find Thomas Brosnan, the nineteen-year-old son of a local blacksmith, Con Brosnan, ‘so that we can crease him’. Brosnan was taken from his home by Private Denis Leen and other soldiers and was walked a few hundred yards in the direction of Castleisland until they met Gaffney on the road. On Gaffney’s instruction and without explanation, Leen shot Brosnan several times in the back. Brosnan was still alive when Gaffney ‘finished him off’.

As the soldiers returned to Castleisland, Gaffney warned his men: ‘Never let on, boys, that we are after creasing that fellow’. He also warned his men not to tell anyone in the army that they were in Scartaglin that day or they would be shot.

WIDESPREAD REVULSION AT BROSNAN MURDER

The murder of Thomas Brosnan prompted widespread revulsion. Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy, who was in Kerry following the death of Sgt Woods, visited the Brosnan family home to express his condolences. According to the Cork Examiner, O’Duffy, ‘who was visibly emotional, expressed to the sobbing father and invalid mother, his deep sympathy in their awful bereavement’. The jury at Brosnan’s inquest returned a verdict: ‘That deceased died from shock and haemorrhage resulting from bullet wounds inflicted by members of the National Army’.

Though Brosnan had been a dispatch-carrier for the local IRA, he had no known involvement in the killing of Sgt James Woods. So, was Gaffney’s targeting of Thomas Brosnan rooted in personal rather than political animosities? For some time before Brosnan’s murder, Gaffney had been in a relationship with Ellen (Lena) Keane, who worked as a nurse in the locality. Ellen Keane was a relative, through marriage, of the Brosnan family of Scartaglin. Her husband had left her a few months after they married and had gone to America. Ellen Keane then began a relationship with Jeremiah Gaffney and they lived together for two or three months. According to evidence later given in court, Ellen Keane became known locally as ‘Mrs Gaffney’.

Con Brosnan and the wider Brosnan family did not approve of Ellen’s relationship with the young National Army officer. As a result, there was bad blood between Con Brosnan and Ellen Keane: according to evidence later given in court, Ellen Keane admitted to pouring Jeyes’ Fluid into Con Brosnan’s well at the back of his house in an apparent case of attempted poisoning.

In evidence subsequently given at trial, Gaffney claimed that Ellen Keane had told him that Thomas Brosnan was involved in the killing of Sgt Woods. It also emerged that after he murdered Brosnan, and when the soldiers were on the way back to Castleisland, Gaffney told his men that he had received information from Ellen Keane that led him to kill Thomas Brosnan.

A LETHAL CONVERGENCE OF PERSONAL AND POLITICAL ENMITIES

The tragic death of Thomas Brosnan therefore resulted from a lethal convergence of personal and political enmities. Gaffney, known to have a violent temper and hatred of anti-Treatyites, used an allegation made by his lover to brutally attack the young blacksmith’s son. His motive was to terrorise not only the Brosnans but also the wider anti-Treaty community in east Kerry. It is also reasonable to conclude that Gaffney believed that the brutal reprisal would never be fully investigated, given the track record of the National Army in covering up extra-judicial killings in Kerry during the Civil War.

Shortly after the murder, Gaffney was brought before District Justice Johnson in Tralee and charged with the murder of Thomas Brosnan on 6 December 1923. In a dramatic development, he escaped from custody while being detained in Tralee. This was a sensation and attracted lurid headlines: a senior figure in the Kerry Command of the National Army, charged with the murder of a nineteen-year-old civilian, escaped from custody and was now on the run. Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy was furious about the reputational damage of Gaffney’s escape from custody, telling the Department of Home Affairs that ‘the escape of a prisoner detained for the most serious crime known to the law, is almost unbelievable’.

On 9 January 1924, Gaffney was arrested following the search of a property at North Richmond Cottages in Dublin, not far from where he had been born. Involved in the search party was none other than Major General Paddy O’Daly, the controversial former head of the Kerry Command.

The government considered the Gaffney case on 10 March 1924. Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins was petitioned for clemency by some of Gaffney’s comrades, who suggested that his conduct in Kerry was ‘foreign to his natural tendencies’. O’Higgins, however, had been particularly disturbed by the behaviour of the army in Kerry during and after the Civil War. After the infamous Kenmare Case of June 1923, for example, when two young women were brutally assaulted by Paddy O’Daly and others, O’Higgins had threatened to resign from government. He and many on the Executive Council at this time were quite content to allow Gaffney to face the full rigours of the law.

TRIAL AND EXECUTION

Jeremiah Gaffney and Denis Leen were put on trial at the Dublin City Commission before Mr Justice Johnathan Pim. Both entered pleas of ‘not guilty’. For the prosecution, William Carrigan SC insisted that Thomas Brosnan ‘was foully butchered in a manner so treacherous, so revolting, that it would be a disgrace and terror to a tribe of savages’. Gaffney was found guilty of the murder and was sentenced to death by hanging. At 8am on 13 March 1924, he was hanged at Mountjoy jail. His execution was carried out by the British hangman, Thomas Pierrepoint. Private Leen was also found guilty but was spared the noose when Gaffney accepted full responsibility for the murder.

The episode was further evidence that elements in the National Army in Kerry were effectively out of control, but by the beginning of 1924 the Executive Council was no longer prepared to turn a blind eye to such behaviour. The fact that two senior soldiers—Leen and Gaffney—were tried and that Gaffney was executed represented a major shift in the approach to army outrages in Kerry and stood in very stark contrast to the cover-ups that typified Ballyseedy and other incidents during the Civil War. For example, Paddy O’Daly, who oversaw the controversial executions policy of early 1923 in Kerry, evaded justice, unlike his lower-ranking colleague. By early 1924, however, the political ground had shifted, the Army Mutiny had taken place, political tensions were high, and the government was keen to enforce law and order in the army as well as in society generally. Gaffney was to be made an example of, and for his brutal crime he paid the ultimate price.

Owen O’Shea is the author of No middle path: the Civil War in Kerry (Merrion, 2022).