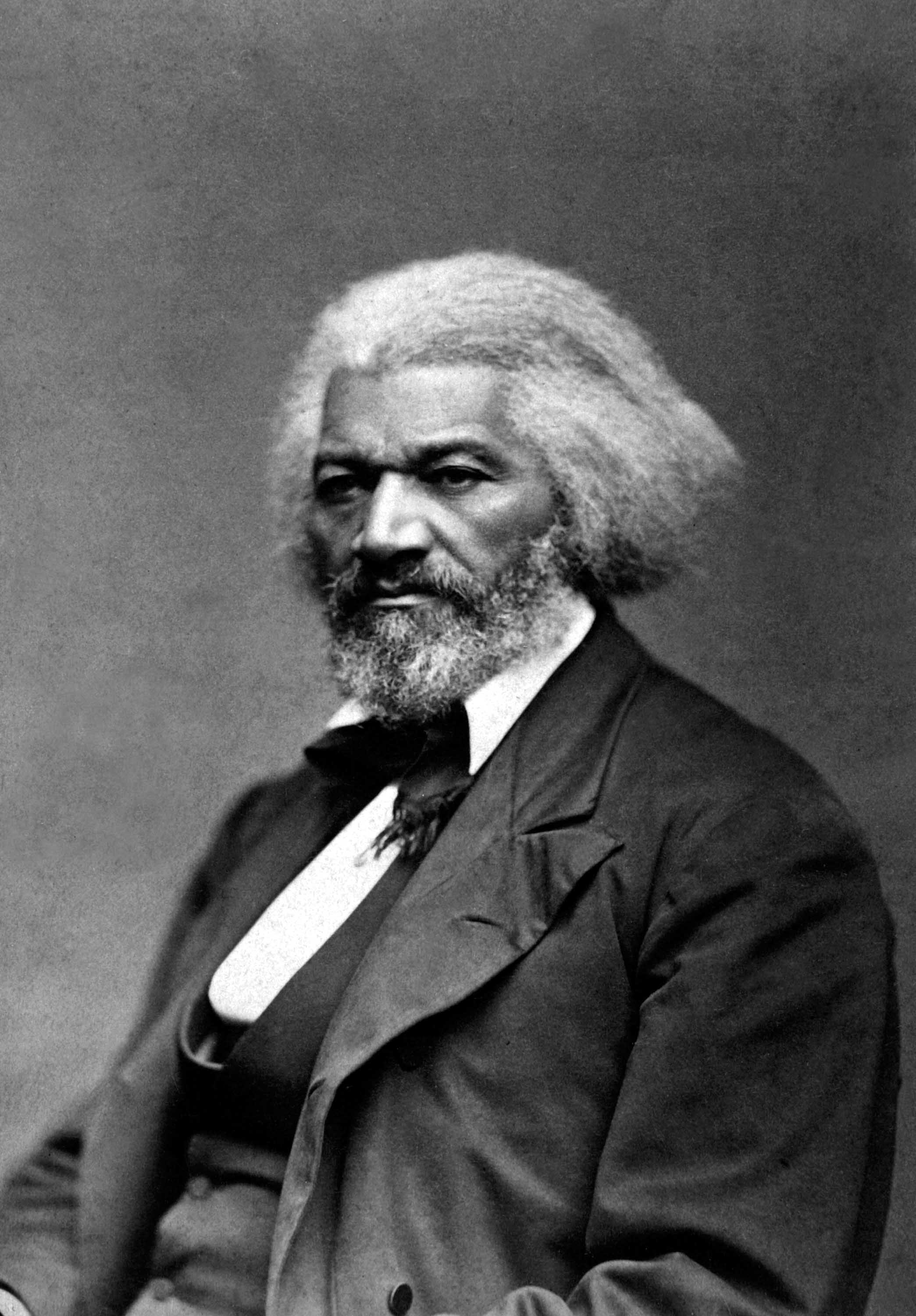

Published in Boston in the summer of 1845, Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave caused an immediate sensation. Denounced as a ‘catalogue of lies’ by newspapers in the slavery-supporting South, it was praised in the North as the ‘most thrilling work which the American press has ever issued—and the most important’. Mixing scenes of great emotional warmth with brutal outrages that shocked readers, the book made a celebrity of its 27-year-old author, an escaped slave from Maryland who had spent most of the previous four years touring and lecturing on behalf of the American Anti-Slavery Society. It also made him a potential target for slave-catchers, as he had disclosed his real name—Frederick Bailey—and that of his owner, Thomas Auld.

The Irish connection

Anticipating the furore that the publication of the Narrative would cause, William Lloyd Garrison and other leading members of the American Anti-Slavery Society decided to send Douglass on a year-long speaking and fund-raising tour of Great Britain and Ireland. This was a well-worn path for American abolitionists, the anti-slavery communities on both sides of the Atlantic having long drawn succour from each other. He would stop in Ireland first, where Garrison arranged to have the Narrative published by his friend Richard D. Webb, the Dublin Quaker printer whose family were at the heart of a small but well-connected anti-slavery lobby in Ireland.

According to Webb’s son Alfred (later a prominent Home Ruler), Webb was ‘the best friend and most active worker the anti-slavery cause had on this side of the Atlantic’. He wrote articles for the anti-slavery newspapers in America, organised their distribution among subscribers in Ireland and opened up his home to an array of visiting abolitionists, including Garrison and Charles Lenox Remond, a free black from Salem, Massachusetts, who had been the most famous black anti-slavery speaker in the country before Douglass. Webb even brought Remond on holiday with him to the west coast of County Clare in 1841, where the formally dressed Quaker and the dark-skinned stranger walking along the cliffs were a great source of amusement for the Irish-speaking locals, especially the

children.

Webb was also central to the gathering together of donations from Britain and Ireland for the annual Boston bazaar, an important American Anti-Slavery Society fund-raiser held just before Christmas, the house on Dublin’s Great Brunswick Street (present-day Pearse Street) filling up with boxloads of handmade purses, bags, pincushions, scarves, gloves, clothing, ornaments and toys each November, the overseas items always fetching the highest prices at the bazaar.

Douglass would travel on board the Cambria, one of the then recently established Cunard Line’s transatlantic steamships. He was accompanied by James Buffum, a 38-year-old white abolitionist from Lynn, Massachusetts. The Hutchinsons, a famous musical family with a strong activist streak, were also on board. Jesse (manager and songwriter), John W., Judson, Asa and Abby had actually shared the stage with Douglass on a number of occasions in the past, working up the crowds with their anti-slavery songs before he launched into his talks.

Genuinely afraid of being ‘spirited away’ by slave-catchers, Douglass was happy to go along with Garrison’s plan, if anxious about leaving his family for so long. He had actually been thinking about just such a trip for several months, excited at the prospect of speaking before international audiences. The tour would surpass all Douglass’s expectations, although there would be some difficulties along the way.

The voyage

Built in Scotland in 1844, the Cambria was the latest addition to the Cunard Line’s Boston–Liverpool transatlantic mail route. It was a 219ft-long wooden paddle-steamer, able to complete in less than two weeks a journey that a short time previously had taken more than a month. The Cambria had room for about 120 people but, with a focus on the delivery of the mail and most of the space allocated to engines and coal, passengers and their comforts were something of an afterthought, as Charles Dickens discovered while travelling on another Cunard ship, the Britannia, a few years earlier, likening it to ‘a gigantic hearse with windows in the side’ in his American notes.

Douglass boarded the Cambria on 16 August 1845. He had a first-class ticket but never saw the inside of his cabin, being relegated to steerage on account of his colour. Buffum went with him in solidarity. Determined to make the most of the voyage, Douglass and Buffum paid little heed to conditions in the part of the ship usually reserved for the poorest travellers. Instead, Douglass recalled fondly how the Hutchinsons often came down ‘to my rude forecastle deck and sung their sweetest songs, enlivening the place with eloquent music as well as spirited conversation’. The Hutchinsons, who became friendly with the ship’s captain, a ‘bluff old sterling Englishman’ named Charles Judkins, also ensured that Douglass was allowed onto the promenade deck each morning, where he could take the sea breeze, watch icebergs float past and marvel at the wide array of passengers on board. There were doctors, lawyers, soldiers and sailors, Catholic bishops, Protestant ministers and Quakers, government officials from Canada, a diplomat from Spain and slaveholders from Cuba and Georgia. He talked slavery to anyone who would listen as the ship made its way across to Ireland, selling copies of his Narrative in full view of disgruntled Americans.

‘I shall never forget the thrill of pleasure and excitement, the eager rush of passengers from cabin to deck, when . . . it was announced by some keen-eyed mariner that the shores of Ireland were in sight,’ wrote Douglass of the evening of 26 August. ‘Our voyage had been a pleasant one and the ocean had been more than kind and gentle to us; but whatever may be the character of a voyage, rough or smooth, long or short, the sight of land, after three thousand miles of sea, ship and sky, is unspeakably grateful to the eye and heart of the voyager.’ The ‘Emerald Isle’, as Douglass called it, was even clearer the next morning, the ragged coastlines of Kerry, Cork and Waterford all coming into view. ‘Oh, the dear spot where I was born!’, exclaimed one passenger from Philadelphia.

Riot

That evening Captain Judkins, acting on a suggestion of the Hutchinsons, invited Douglass to deliver a speech on slavery on the quarterdeck. The ship’s bell was sounded and a large number of the passengers gathered around. Judkins introduced Douglass before sneaking away to his cabin to sleep off the champagne he had been sharing with the first-class passengers at the traditional captain’s dinner on the last night of a voyage. The Hutchinsons sang an anti-slavery song and Douglass began to speak, quoting some slave laws from Georgia. ‘That’s a lie,’ called one of the passengers as soon as he had finished his first sentence. Douglass tried again. The hecklers, however, led by a Connecticut man named Hazzard, became more violent, more insulting. ‘Down with the nigger,’ one shouted. ‘He shan’t speak,’ yelled another. ‘Oh, I wish I had you in Cuba,’ said a third. Other listeners, including an Irish soldier, Captain Thomas Gough of the 33rd Foot, encouraged him to continue. It was not long before the whole scene verged on riot, with passengers who half an hour previously had been drinking each other’s health now shouting furiously into each other’s faces and clenching their fists.

Douglass gave up, disappearing back down below decks. The arguing, however, went on without him, one passenger threatening to throw ‘the damned nigger overboard’, to which the 6ft-plus Gough replied, ‘Two might play at that game’. Captain Judkins, woken by an aide, returned to the deck and threatened to put the pro-slavery ‘mobocrats’ in irons. Order finally restored, the Cambria sailed up the Irish Sea, docking in Liverpool on the morning of Thursday 28 August. Two days later, the Cambria carried Douglass and Buffum across to Dublin, the cramped and crowded city of almost a quarter of a million souls that would be their home for the next six weeks. It was the start of a four-month tour that Douglass would always consider one of the most transformative periods of his life.

Laurence Fenton is a writer and editor living in Cork.

Read More: Captain C.H.E. Judkins

Journey home

Further reading

F. Douglass, My bondage and my freedom [1855] (London, 2003).

L. Fenton, Frederick Douglass in Ireland: ‘the Black O’Connell’ (Cork, 2014).