By T.K. Moloney

In September 1919 a body lay in state in a coffin in a private house on the sloping Main Street of Killaloe, Co. Clare. A boy of six was brought in to view the body and pay his respects. He was a distant relative of the deceased, but the connection was cherished by the boy’s family, and it was easy for them to render homage to the great man because they lived nearby. The individual in the coffin had been a military man, reflected in the uniform he now wore in death, but he had not been a combatant; he had held very high officer rank in the British Army but, unlike the majority of his fellow officers at that time, he was Catholic. His family, though not poor, were not wealthy and did not possess land, property or influence to any extent, unlike the families of many Anglo-Irish or British officers.

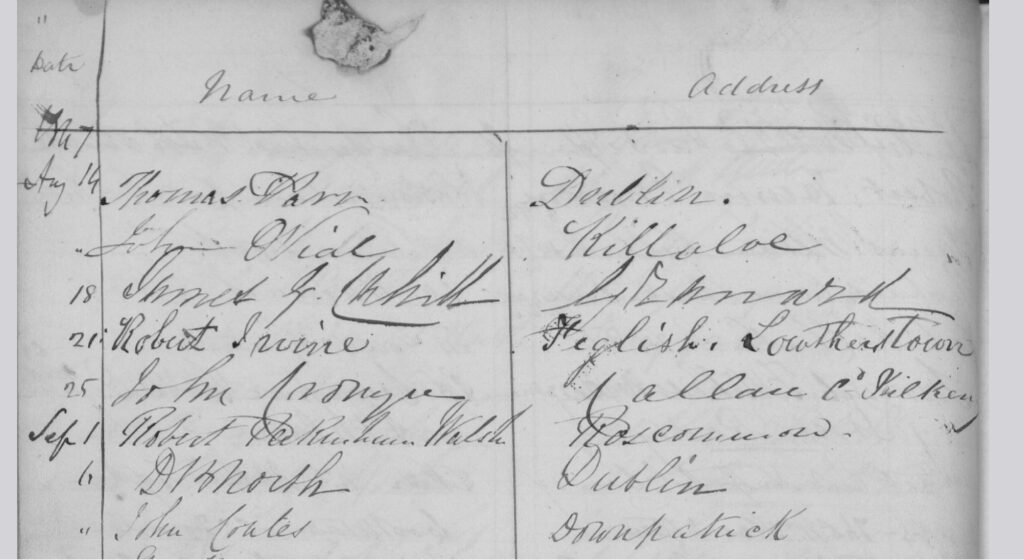

The body was that of Surgeon-General John O’Nial CB, born in Killaloe, Co. Clare, in June 1827, the son and nephew of doctors. While Catholics were not formally excluded from studying medicine under the penal laws, it had become easier to get education and training at home and to join the profession in the decades during their gradual repeal. John Junior (his father was also called John) got his medical licentiate in August 1847 from the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin, aged twenty, as did his younger brother Daniel eleven years later; another brother, William George, was also a doctor. His unusual surname, also written Niall, is an archaic variation of Nihill or O’Neill, and his branch was the only one of the family before or since who favoured the ‘O’.

SERVICE IN SOUTH AFRICA, INDIA AND AFGHANISTAN

In April 1852 O’Nial joined the army medical corps and was appointed assistant surgeon to the 91st Regiment of Foot (mainly recruited in Scotland and known as the Argyllshire Regiment), which was based in Enniskillen that year, and later served in the ‘Kaffir Campaign’ of 1852–3 in South Africa, the final and most hard-fought campaign against the Xhosa people. Returning to Europe, he served in Greece and the Ionian islands (the latter a British protectorate). Then, to take up service in the Indian Army, he travelled to India via Alexandria, Suez and Aden, where his ship picked up coal, eventually arriving via Bombay in Poona (now Pune) in western India in early October 1858. He was appointed surgeon-to-the-staff in May 1859 and transferred to the 51st Foot in June 1861. By 1863 he was serving on the North-West Frontier of India, taking part in the Umbeyla expedition, a fraught campaign in which the British forces lost almost 1,000 men, with many more wounded. He was appointed surgeon-major in April 1872, having completed twenty years in the service, and, returning to England on leave, attended a levée or royal reception held by the Prince of Wales at St James’s Palace in June 1874, where numerous army medical men were also presented.

O’Nial organised and provided medical care at the battles of Jawaki (1877) and Ali Masjid (1878), engagements in the Second Afghan War, in which the British invaded Afghanistan to counter the Russian threat from the north. These were smaller expeditions with fewer casualties, after which the British occupied several cities and towns, including Kandahar. For a period up to August 1879 O’Nial was in medical charge of the Deolali depot in Rajasthan, a staging post for newly arrived troops acclimatising to India and for others waiting to return home. Owing to the poor conditions there, and the subsequent effect on morale and mental health, the name gave rise to British soldiers’ slang for going mad—‘doolally’.

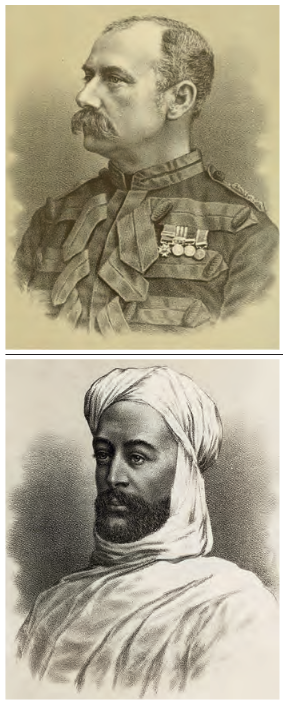

O’Nial was promoted to the then new rank of brigade surgeon in November 1879, and then to deputy surgeon-general in May 1880, finally becoming principal medical officer of the 1st Division of the Kandahar Field Force. Following the defeat of a British force led by General Burrows deployed from Kandahar to intercept an advancing Afghan army at Meiwand and its subsequent retreat to Kandahar, the city was besieged by the Afghan army. When Burrows had left the city there were already numerous sick, but on his return with further sick and wounded the medical situation was dire indeed. General Primrose was in command in Kandahar; O’Nial was among the staff officers of his forces trapped in the city and ‘had charge of the whole sick and wounded during the defence of that fortress and subsequent operations’. It was he, as deputy surgeon-general, who reported to the relieving General Roberts that the number of sick was no less than 1,000. In recognition of his achievements in Afghanistan, in July 1881 he was conferred with the Order of Companion of the Bath (CB) by Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. After almost 30 years abroad, he was transferred back to the UK in 1882 and appointed principal medical officer of the Northern Command.

NILE EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

The Nile Expeditionary Force was established in 1884 to rescue General Gordon, then besieged by the Mahdi’s forces in Khartoum. O’Nial was appointed as principal medical officer to the expedition, and after the fall of Khartoum in January 1885 he subsequently served with the Sudan Frontier Field Force from 1885–6 until his retirement in October 1887. This African service was the pinnacle of his career. Lord Wolseley’s Nile expedition was composed of 11,000 troops, labourers and boat-handlers. O’Nial, together with officers and men of the Medical Staff Corps, provided health facilities for the combined force. The army had 27 field hospitals (ranging from twelve to 500 beds) along the Nile, from Aswan in southern Egypt to Korti in north central Sudan, a distance of over 1,250km. The larger facilities had up to four doctors and 40 staff. Much of the transport was by river. Major-General Henry Brackenbury, quartermaster, tasked with providing food for men and animals as well as ammunition, equipment and supplies, noted that:

‘Accordingly, I visited Korti, and there saw [Deputy] Surgeon General O’Nial, the principal medical officer, and Surgeon Major Harvey, who was selected as senior medical officer of the river column. They met me in the fairest way. I agreed, on General Earle’s part, to give them one boat for each of the eight sections of the field hospital, and a ninth boat for the medical officer, in which he could take comforts for the sick, and to furnish a sufficient number of men to make up, with the men of the medical staff corps, crews for the boats.’

O’Nial and Harvey (who had served with him at Kandahar) agreed to limit the equipment to the exigencies of a flying column, ‘which must carry forward with it, and cannot leave behind or send back, its sick and wounded’. The deputy surgeon-general succeeded extraordinarily well in co-ordinating and delivering the medical aspects of that vast undertaking. A dispatch from Lord Wolseley, printed in the Standard on 26 August 1885, averred that the medical department had been ‘administered with ability by Deputy Surgeon O’Nial’. Wolseley had never seen sick and wounded better cared for and listed O’Nial among those deserving of special mention. In the same month O’Nial received his last promotion; he would retire with the rank of surgeon-general.

RETIREMENT

O’Nial never married, but in his youth he fell in love with a lady called Sarah Doyle from Killaloe. When he went into the Indian Army, her family, cruelly judging that she should not wait for him, did not give her his letters. She ‘went into a decline’ and died. After her parents died, he bought their house in Killaloe in order to live in it and preserve his memories of her. He was remembered as a stiff old gentleman who ran everything in his house to a timetable and took care not to catch cold in winter by wearing earmuffs outdoors. In 1890 he received a public apology from General Redvers Buller over a remark he had supposedly made during the Khartoum expedition. Buller, giving evidence before the War Office Committee presided over by Lord Camperdown, claimed that a medical officer (O’Nial) had refused a camel on the grounds that it was ‘not good enough for a major-general’. He cited this as an instance of the evils of honorary military rank for medical officers. When it was pointed out to him that this statement was totally without foundation, he apologised to Surgeon-General O’Nial for giving currency to ‘an idle story’.

In spite of his career in the British military, O’Nial was not unionist in politics but supported Home Rule, and he contributed £5 in 1902 and £10 in 1904 to the Irish Parliamentary Party in support of William Redmond, then MP for East Clare. He was, in the words of the Freeman’s Journal of 3 June 1894, another of ‘those patriotic Irishmen whose loyalty to their country is the best and the only necessary answer to the boasts of the unionists that all “the wealth and intelligence” of the country approves the maintenance of the union in its present preposterous shape’.

He lived on quietly in Killaloe with his two nieces, the Kennedy sisters, daughters of his sister Honoria. Aged 71, he visited Bath in March 1898 and stayed at the Grand Hotel along with other luminaries, as announced in the Bath Chronicle. In 1911, under the heading ‘notable men and women’, the London daily Telegraph wished him congratulations on his 84th birthday. He died on 1 September 1919, was waked in his home and was later buried in the shadow of St Flannan’s Church of Ireland cathedral in Killaloe, a short distance from his residence. He left a will with ‘effects’ of £39,059 18s. 1d., which included land, property and fishing rights, and in 1924 his house was sold, along with its memories of Sarah Doyle, to John Crowe, a local businessman. O’Nial was a pioneer for Irishmen aspiring to provide medical care from the lowest to the highest levels in the British Army in the nineteenth century, a role previously dominated by Englishmen and Scotsmen.

The six-year-old boy always remembered seeing him in his coffin and the military men who attended his funeral, and he passed those memories on to his son, the author of this article.

T.K. Moloney is a history graduate of Maynooth University.

Further reading

T. Archer, The war in Egypt and the Sudan: an episode in the history of the British Empire, vol. III (London, 1886).

D. Featherstone, Colonial small wars 1837–1901 (Newton Abbot, 1973).

G.L. Goff, Historical records of the 91st Argyllshire Highlanders (London, 1891).

B. Niall, My accidental career (Melbourne, 2022).