By James K. Meighan

Convicted of sabotage and conspiracy at the Rivonia trials in South Africa, on 20 April 1964 Nelson Mandela, while awaiting a potential sentence of death, proclaimed from the dock his respect for and belief in the Magna Carta by observing that the charter was ‘held in veneration by democrats’ worldwide. The charter is seen by many as the seminal document that released, slowly, the tight grip of absolutism and as one of the early shoots of human rights, from both a public and a private perspective. It is recognised as the first document in the British uncodified constitution, laying the groundwork for the Petition of Rights (1628), the Bill of Rights (1689), the Human Rights Act (1998) and the myriad of statutes enacted by the British parliament. The Magna Carta Hiberniae, while not as publicly recognisable as the original charter, did for the Irish what the Great Charter did for the English and served as both a modernising and an equalising force, showing the Irish (or at least the minority to whom the charter applied) that the English monarch was willing to bestow the benefits of the charter on his Irish subjects, at least on paper.

BACKGROUND

Henry II, the first Plantagenet monarch, reigned from 1154 to 1189, during which time the English gained significant territory. By inheritance and marriage Henry gained vast stretches of land from the Channel to the Pyrenees, and through conquest he added lands in Brittany, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Richard I, known as the Lionheart, who focused his energies and the monarch’s purse on international issues, including the costly crusades in the Holy Land. Upon Richard’s death in 1199 his brother John ascended the throne, after significant disagreement with his fifteen-year-old nephew, Arthur of Brittany (son of John’s deceased brother Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany), which resulted in Arthur’s disappearance; it is believed that he was murdered by John or by an assassin on John’s behalf. John’s treatment of Arthur undermined his authority over the barons and provided them with another grievance against the monarch. John lost vast swathes of territory in France as the local barons grew weary of the constant wars perpetrated by his father and older brother. He commenced an inevitably unsuccessful campaign to regain the lost French territory, and the bill for these persistent and expensive wars fell in large part on the English barons. Consequently, in 1214 they demanded a charter from the king that would guarantee good government. Negotiations broke down, however, and by May 1215 the barons had declared war on the king. When they occupied the city of London John was left with no choice but to negotiate.

In the meadow of Runnymede, which runs alongside the River Thames, midway between London and the king’s castle at Windsor, the barons and John met over five days to negotiate a settlement. Terms were agreed and, on the afternoon of 15 June 1215, John issued the royal assent to a list of demands that would form the basis of the Magna Carta (Great Charter). Ten weeks later, however, John repudiated it, provoking the Barons’ War (1215–17). He died on 19 October 1216 and was succeeded by his son, Henry III. The charter was reissued on three occasions by Henry, in 1216, 1217 and 1225; nearly a third of the original charter was amended during the evolution of its three subsequent versions. When considering the effect of the charter, one should not consider it as a formal legal document in the contemporary sense, as historian J.C. Holt has observed: ‘Sometimes Magna Carta stated the law. Sometimes it stated what its supporters hoped would become law. Sometimes it stated what they pretended was law.’

THE GREAT CHARTER

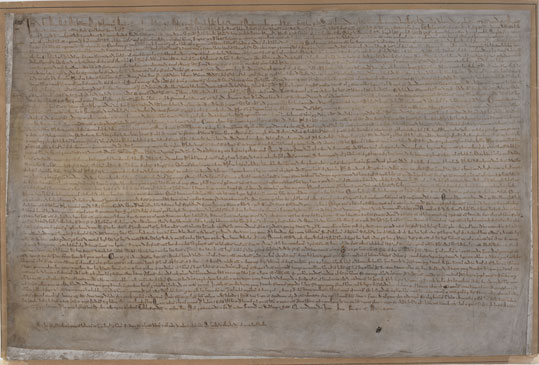

The original document contained 63 articles and addressed issues such as public administration, taxation, criminal justice and the royal abuses of feudal customs. The charter was composed in Latin, the language of religious liturgy, of scholarship, and of secular and ecclesiastical government. Of the 63 articles, only four remain part of English law today: defending the liberties and rights of the English church (articles 1 and 63); confirming the liberties and customs of London and other towns (article 13); and giving free men the right to justice and a fair trial (article 39).

In modern terms, the charter is remembered for a number of key concepts: individual rights; strengthening parliament’s powers, particularly as regards taxation; and certain rules around the navigation of rivers and the standardisation of weights and measures. On personal rights, the charter spoke in lofty terms but was limited as regards specifics. Nevertheless, at this remove it is recognised as the forerunner for rights such as trial by jury, the principle of habeas corpus and the property rights of the individual. A major concession gained by the barons was the protection granted concerning the taxation of the individual, which would go on to recognise the concept of ‘no taxation without representation’ and the allocation of powers in favour of parliament to ensure that the monarch could no longer unilaterally impose taxes without the input, views and opinions of a common council. This concept also opened the door to the transfer of other powers to parliament in the centuries since. Article 39 is considered one of the most significant and provided that ‘no free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land’. It has been argued that article 39 was the basis for the concept of trial by jury, although the modern view is that it does not extend that far as we would understand it today. The concept of due process was not recognised until the statute of Edward III in 1352 but article 39 is regarded as the first step in that direction.

The rights enunciated should be put into context. Only a small proportion of the population was entitled to rely on these rights. The charter made reference to ‘all free men’, but the vast majority of the population at that time were unfree peasants. The charter limited the applicability of its articles to women. While it did contain clauses that protected the rights of widows, heiresses and female orphans, the impulse was deeply reactionary—to exclude half of the population from judicial procedures henceforth available only to men. Article 54 prohibited any woman from accusing a man of murder or manslaughter, save in accusations that involved her husband. It is believed that the intention of this article may have been to improve the efficiency of the king’s courts, disposing of malicious indictments by women—themselves, it was argued, merely acting as agents of other men.

To ensure John’s compliance with the charter, article 61 provided for a council of 25 barons to be elected to monitor the king’s adherence. The king immediately attempted to undermine the charter by writing to Pope Innocent III in July 1215, arguing that the charter compromised the pope’s rights as John’s feudal lord. John hoped that the pope would annul the charter, which he did by way of a papal bull on 24 August 1215, thereby justifying John’s repudiation of it.

Magna Carta Hiberniae

The Irish barons took no part in the war between the monarch and their English fellow barons. They were content to look after their own affairs and to let the monarch and his English nobles fight it out. Following the death of King John in October 1216 there was a marked alteration in English policy towards Ireland, and Henry III wanted to consolidate his control over the various elements within his realm. The first official communication to the justiciar (chief governor of Ireland), Geoffrey de Marisco, in November 1216 advised that the new administration wanted to repair relations between Ireland and England and concluded that the king willed that his subjects in Ireland should have the same liberties as had been granted to his subjects in England. On 12 November 1216 Henry III issued the Great Charter of Liberties to Ireland (Magna Carta Hiberniae), and it was sent to Dublin in February 1217. The Irish charter was almost identical to its English counterpart, apart from a number of obvious amendments. The Irish document substituted Ireland for England, Dublin for London, and the Liffey for the Thames and the Medway throughout. Otherwise there was no difference between the original English and Irish charters. The noted historian on the Irish charter, H.G. Richardson, observed that ‘the Irish Government of 1217, or any other authority, solemnly recast the original text with so clumsy and inadequate a result; for, granted that the authentic charter of 1216 was the law in Ireland, this crude substitution of names could not be justified on any principle of interpretation known to medieval (or modern) lawyers’. The Magna Carta Hiberniae was published in the Red Book of the Irish Exchequer (a manuscript compilation of precedents and office memoranda of the Irish Exchequer) in the fourteenth century, but was destroyed in the burning of the Public Records Office in the Four Courts during the Irish Civil War in June 1922.

There has always been some suspicion about the authenticity and provenance of the Irish charter. As there is no record of it before its appearance in the Red Book in the fourteenth century, some historians have argued that, while Henry III may have sent a charter to Ireland in February 1217, it would have been identical to the English one and that the Irish references in the document were only included when its contents were later transcribed into the Red Book. Since the Red Book has been destroyed, however, there is no way to prove or disprove this hypothesis.

THE LEGACY OF MAGNA CARTA

The purpose for which the charter was drawn up was as a peace treaty. Following its annulment by Innocent III, however, John repudiated it, which set the king and barons on the road to the First Barons’ War. Thus as a peace treaty the charter failed completely. Nevertheless, as a seminal statement on the manner in which the monarch and his barons should interact and as the first real release of an absolute monarch’s grip on society and his subjects, it can be seen as a great success. Following its enunciation, the monarch’s power in England was never restored to its previous heights; successive kings and queens eventually accepted the premise of the charter and sought, in the main, to work within its confines.

The charter has become a symbol of the foundational concepts for justice and liberty, and some of the most fundamental international constitutional documents—including the United States Bill of Rights (1791), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the European Convention on Human Rights (1950)—have drawn ideas from it. While it is true that the charter is now an object studied more by historians than by lawyers, it does continue to have contemporary relevance to the modern legal world. Historian Kent Worcester has observed that ‘Magna Carta is constitutive to the Anglo-American legal tradition—and, after all, nearly a thousand federal and state courts have cited the Magna Carta in formal decisions, and, in the half-century between 1940 and 1990, the Supreme Court cited the text in over 60 cases’.

CONCLUSION

Internationally, the late Middle Ages would have seen similar monarchical concessions to the Great Charter, but such concessions did not stand the test of time. The reasons for the indelible mark of the charter are many, and historians have noted that its most significant element is its living and lasting effect for over 850 years. Unlike its Irish counterpart, four original copies of the Magna Carta of 1215 exist today: one in Lincoln Cathedral, one in Salisbury Cathedral and two in the British Museum.

Irrespective of Henry III’s motives for granting the Magna Carta Hiberniae to Ireland, owing to the cosmetic alterations between the versions, albeit significant in the Irish context, the history that applies to the original charter, granted in the meadow of Runnymede, applies with equal force to the charter granted to the Irish in November 1217. John’s son, Henry III, understood that there had been a shift in the constitutional position of the protagonists since the original charter, and in 1225 he freely issued a version of the charter in return for a tax granted to him by the whole kingdom. The majority of the charter has been repealed from the statute book, but its ideals live on. The principles for which the barons sought relief in Runnymede and subsequently, and the Irish through the Magna Carta Hiberniae, continue to have contemporary relevance, to ensure that there are sufficient safeguards in place against unchecked or immutable power.

James Meighan is a solicitor and a Ph.D candidate at the University of Limerick with an interest in constitutional and legal history.

Further reading

Cosgrove (ed.), A New History of Ireland, Vol. II. Medieval Ireland, 1169–1534 (Oxford, 1987).

J.C. Holt, Magna Carta (Cambridge, 2015).

A.L. Poole, From Domesday Book to Magna Carta 1087–1216 (Oxford, 1963).

W.L. Warren, King John (London, 1978).