National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks

By Donal Fallon

For many people, RTÉ’s Brainstorm website offered a first introduction to the work of museum curator and GAA historian Siobhán Doyle. While live sports were absent for much of 2020, Doyle’s fascinating insights into the history and culture of the Gaelic Athletic Association explored subjects as diverse as the rise of commemorative jerseys and how bad weather had affected the game historically. In a year when the All-Ireland Senior Football Final was played six days before Christmas Day, it was the kind of thing that supporters of the game may have pondered.

In recent years Doyle has been exploring the material culture of the GAA and its community, leading to the publication in 2022 of A history of the GAA in 100 objects with Merrion Press. This book followed on from a moment in Irish publishing and historiography, with Fintan O’Toole’s A history of Ireland in 100 objects and John Gibney’s A history of the Easter Rising in 50 objects, just two examples of previous works taking a similar approach. Unsurprisingly, a study around the largest sporting body on the island would prove to have an interesting afterlife, with Doyle continuously encountering new objects and personal stories since the publication of the book.

Now a physical exhibition brings some of these 100 objects to the National Museum of Ireland, alongside ancient treasures from the permanent collection, while also building on the multi-media and interactive potentials of such an event. Although hosted in the capital, the exhibition touches on every corner of Ireland and includes the diaspora, and is conscious of avoiding an over-emphasis on the more familiar names and characters within the story of the organisation. While questions remain today about the ideal future relationship between the Camogie Association and the Gaelic Athletic Association, which remain separate bodies, the ‘GAA’ is understood here to encompass native games across all associations.

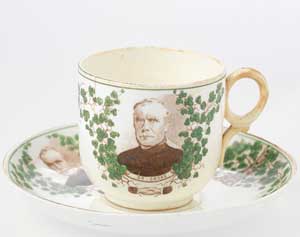

The GAA formally came into existence following a meeting in November 1884 in Hayes’ Hotel, Thurles, Co. Tipperary. Its choice of patrons was intended to include the broadest sweep of Irish nationalist opinion, with approaches made to Archbishop Thomas Croke of Cashel, Land League icon Michael Davitt and constitutional nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell. Despite the strong nationalist ethos behind the foundation of the body, sports historians (including Paul Rouse in Sport and Ireland: a history and Marcus De Búrca in his landmark overview of the body) have demonstrated that recreational pursuit was for many protagonists the primary driving force in their participation. Doyle’s exhibition does a great job of balancing the political and the personal, understanding the GAA first and foremost as a sporting body.

The earliest item the visitor encounters is a medieval mether. A mether, the museum informs us, ‘can be described as a two- or four-handled medieval wooden drinking or storage vessel that typically features a quadrangular mouth tapering to a narrower rounded base’. Of course, its appearance instantly recalls the Liam McCarthy Cup. There are several examples of methers in the permanent collection of the NMI, and here we are treated to one discovered at Corran, Co. Armagh. It is a reminder that the founders of the GAA sought to look back into an ancient Irish past for inspiration and identity.

With its emphasis on design history, the Collins Barracks site has long displayed Irish fashion artefacts and exhibitions, including a much-loved retrospective of the work of Ib Jorgensen. In this exhibition we encounter proposals from designer Neilí Mulcahy, submitted in 1969, for what camogie apparel should look like. From the mid-twentieth century there were increasing demands for less-restrictive playing wear. In the earliest days of the sport, women who participated ‘were forced to put modesty over practicality’. Also displayed is a tweed camogie dress worn by Maeve Gilroy, a celebrated Antrim player of the 1960s and part of the team which halted Dublin’s march to nineteen All-Ireland titles in a row.

While care is taken not to over-emphasise the political dimensions of the organisation, there are still numerous artefacts that offer revealing insights into the revolutionary period. One such, a hurl owned by Michael Collins, is a reminder of the international dimensions of the revolution. A member of the Geraldines GAA club, Collins was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood in London by none other than Sam Maguire, who worked as a sorter with the Royal Mail. Many young Irish men and women lived double lives in the city at the heart of empire, but the hurl is a reminder that recreation and revolution both had their place. Another curious item from the revolutionary period is a rugby ball from the Frongoch internment camp in Wales. In the absence of the correct ball, it was used to play Gaelic football—no easy achievement! Memories of playing sports in Frongoch are frequent in the Bureau of Military History witness statements, with Irish Volunteer Daniel Tuite recalling how ‘each day we were allowed into a recreation field enclosed by barbed wire and guarded by sentries, where we played various games, including football, running, jumping, weight-throwing …’. More than just being the ‘university of revolution’ where political and military strategies were debated, Frongoch converted some into sporting Gaels.

Some of the items on display are seemingly everyday items of our own time but they can reveal surprising tales. A yellow sliotar, used in the 2020 All-Ireland senior hurling final between Limerick and Tipperary, reminds us that the replacement of the traditional white sliotar was not motivated by aesthetic concerns but by rigorous tests to improve the quality of the game.

Like the Troubles Gallery in Belfast’s Ulster Museum, which invites the visitor to leave their own memories or observations, this exhibition encourages visitors to leave personal memories of the GAA in their own lives, with the promise of a future exhibition archive that will preserve these stories. It is a reminder that the work of collecting the story of the GAA will never be done, as the sports and the organisation continue to evolve and change with broader Irish society.

Donal Fallon is the presenter of the Three Castles Burning podcast and author of Three Castles Burning: a history of Dublin in twelve streets (New Island Books, 2022).