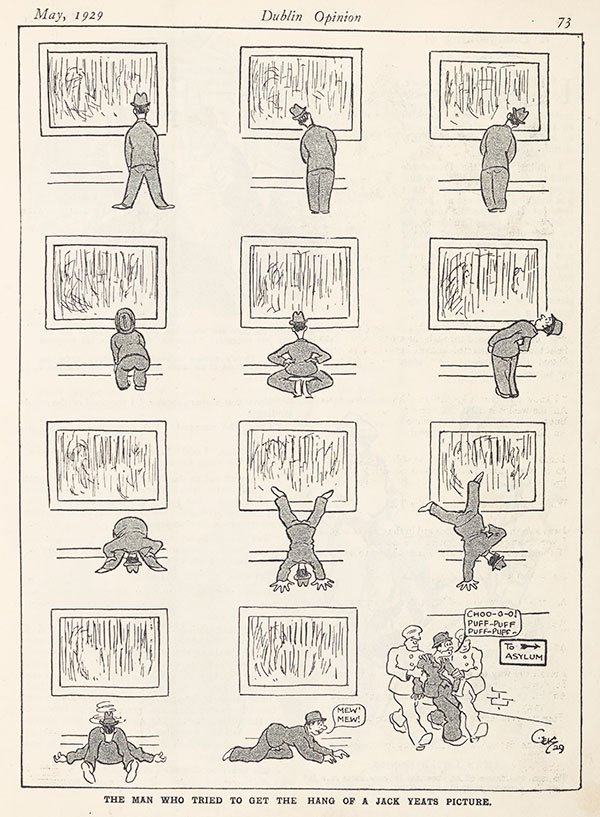

By Róisín Kennedy

In a much-quoted letter, written in 1938, the writer Samuel Beckett expressed his ‘chronic inability to understand … a phrase like “the Irish people” or to imagine that it ever gave a fart in its corduroys for any form of art whatsoever, whether before the union or after, or that it was ever capable of any thought or act other than rudimentary thoughts and acts … or that it would ever care or know that there was once a painter in Ireland called Jack Butler Yeats!’ Beckett was writing to the art critic and future director of the National Gallery of Ireland Thomas MacGreevy. Referring to an early draft of the critic’s monograph on Yeats, Jack B. Yeats—an appreciation and an interpretation, Beckett was clearly unhappy that MacGreevy was using Yeats’s work for nationalist ends, a sentiment that was to intensify by the time the book was published in 1945.

Different ideas on the role of visual art

It is evident that MacGreevy and Beckett, despite their close friendship and keen regard for the work of Yeats, had very different ideas on the role of visual art. For MacGreevy, Yeats’s painting was significant in manifesting the experience of Irish life in a manner that could be shared by a cross-section of the population. His book sets Yeats’s paintings in the context of the political history of modern Ireland, arguing that they filled a need for the expression of everyday life in Ireland. Beckett advocated instead a much more individualistic role for art, believing that MacGreevy’s text had oversimplified the complex meanings of Yeats’s work and its relationship to the viewer.

Writers like MacGreevy and many other artists, critics and art-lovers in post-independence Ireland were aware of the general indifference towards visual art in Ireland amongst their fellow Irishmen and women. One of the primary goals of their writings and activities was to convince the public that visual art mattered and that it was relevant to their lives and their imaginings. The apathetic attitude towards art was attributed by many commentators to colonisation. Easel painting had been introduced into Ireland as part of the colonial process in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and it was widely assumed that art made in Ireland was ‘essentially English’. Lack of patronage of art, especially after the Act of Union, impelled ambitious Irish artists to migrate to England, where their nationality was subsumed into all-inclusive Britishness. The confusion over the Irishness of the artist persisted until well into the twentieth century, when many successful Irish artists continued to be regarded as British (or English). One of the specific intentions of MacGreevy’s book on Yeats was to proclaim him and his work as distinctively Irish and to make that work relevant to modern Ireland.

Visual art in the Irish Free State

In the post-independence period colonialism continued to influence perceptions of visual art. The Irish Exhibition of Living Art, an annual exhibition forum for modern art founded in 1943, courted London-based critics, curators and gallery-owners to further the careers of its exhibitors. In the 1960s, the London-based judges of the Carroll’s Prize awarded at the Living Art exhibitions in Dublin encouraged young Irish artists to familiarise themselves with the emerging trends in British and American art. Their comments reinforced the idea that Irish art was backward in comparison to that of London and New York. The exclusion of Irish artists from the major Rosc exhibitions of 1967 and 1971 likewise confirmed the inferior status of Irish art. The deference shown to British and, increasingly, American cultural values by Irish artists and critics was seen as the embodiment of a deep-seated inferiority complex, one that ultimately derived from the state’s post-colonial status. In 1968 the writer Desmond Fennell maintained that Irish insecurity regarding its own cultural identity and position had resulted in the Irish looking elsewhere for validation.

The Irish Free State downgraded art within the new educational and cultural hierarchy by dropping drawing as a compulsory subject at primary-school level in 1922. It was not put back into the curriculum until 1971. As Declan Kiberd has written, independent Ireland’s ‘educators barely concealed their snobbish contempt for those who actually made things with their hands’. Furthermore, until the introduction of free second-level education in 1967, only those attending private religious-run schools could avail of art classes. This education system in which only the privileged had access to art further encouraged an élitist engagement with visual art in Ireland. Already associated with colonialism, art continued to remain marginalised from the rest of Irish cultural life. The neglect of art education had long-term implications for public awareness of the relevance of art and design. In 1961 a group of visiting Scandinavian designers noted that, ‘without some reasonably developed form of art education in the various levels of schools in Ireland, it will be impossible to produce the informed and appreciative public so necessary as a background to the creative artist’.

Notwithstanding its ambivalent attitude, the Irish state was aware of the benefits of using art to project a sophisticated image of Irish identity to an international audience. Works of art were commissioned for international exhibitions, and the Cultural Relations Committee, established in 1947, facilitated Ireland’s participation in the major international exhibition of modern art, the Venice Biennale. Nevertheless, most initiatives that espoused the exhibition and dissemination of Irish art came from individuals and private organisations.

‘Very safe, very pretty’

Their views are manifest in the widespread coverage of modern art in newspapers and periodicals from the 1920s into the 1970s. These reveal the pervasive exhibition of art and the activities of private exhibition societies and organisations, such as the Friends of the National Collections of Ireland and the Irish Exhibition of Living Art, that were devoted to the dissemination of modern art. The recurring disputes that these ignited are surprising, given that modern Irish art lacks the overt radicalism that is usually associated with orthodox modernism. Patrick Kavanagh summarised modern art in Dublin in 1940s as ‘a collection of works very safe, very pretty, with just exactly the right amount of harmless shock to please the conventional middle-class mind’. Two decades later, the painter Michael Kane wrote that the kind of art favoured by the Irish élite was that which succeeded in ‘affecting the most convincing simulation of vigorous modernism while giving least offence’. One can counteract these viewpoints by quoting Ernie O’Malley on Yeats’s late painting. He described how the figures in the work enter a subjective world in which they ‘are related to the loneliness of the individual soul, the vague lack of pattern in living with its sense of inherent tragedy, brooding nostalgia associated with time as well as variations on the freer moments as of old’. Or consider Brian O’Doherty writing on Patrick Collins’s work in the 1970s:

‘Within the complex surface of his paintings … Collins creates an ambiguous sense of space and form. Their nebulous quality is comparable to the labyrinthine effect of early Christian manuscripts … the obscure appearance of the landscape is related to a characteristically Irish attitude, that strange Irish distrust of the senses.’

Modern art, through its emphasis on form and individual contemplation, provokes these diverging views, each valid in its own terms.

Why modern art?

Why was modern art championed? It provided a way to project a unified and distinctive image of the nation state. It offered a new artistic language that differed from colonial art and that projected positive conceptions of Ireland. This is found, for example, in the work of Paul Henry, prized for its ability to project timeless images of the west of Ireland but in the language of modernism. The controversies surrounding its reception suggest, however, that Irish modern art was at times subversive and questioning of dominant cultural values and that the exhibition of modern art by non-Irish artists could be especially divisive. The need to defend the (Catholic) Irish people from the decadence of modern art is a recurring aspect of the debate, especially in the early decades of the new state. In 1948 Count Paul Biver warned those seeking to erect Andrew O’Connor’s Christ the King sculpture in Dún Laoghaire ‘that [the work] might suit the fancy of some futurist artists of Montmartre but shall be a scandal for good, plain, Catholic people …’. In 1942 the lord mayor of Dublin, Kathleen Clarke, declared of Rouault’s Christ and the Soldier that, ‘as this is a Christian country, it might be offensive to put it on exhibition in a public gallery’.

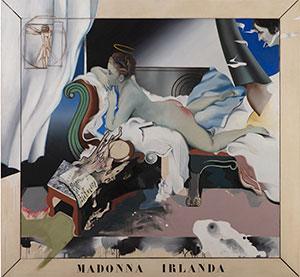

The subversive imagery and processes of modern art could communicate a sense of the country’s fragmented identity. O’Malley, for example, drew attention to the predominance of the dislocated figures in Jack Yeats’s work, ‘the sailor, tinker, ballad singer and circus performer who bear much the same relationship to the tightened security of bourgeois respectability … as does the artist to that life’. David Lloyd has identified the complex use of paint in the later work of Yeats as a deliberate ‘disengagement of aesthetic from apparent political ends’. Nicholas Allen has connected the work of Yeats to the wider cultural fallout of the Civil War and the inability of the Irish Free State to resolve the inherent contradictions of its foundation. In this analysis, Yeats’s work reflects the discrepancies between the real and imagined experience of modern Ireland. Modern art continued to challenge prevailing ideas of Irishness into the 1970s. Micheal Farrell’s Madonna Irlanda, Ireland’s First Real Political Painting (1977) articulates the rage and dislocation experienced by the artist in response to the Northern Irish crisis. Its desecration of the allegorical Mother Ireland makes a clear statement on the disintegration of established ideas of Irishness and unintentionally reveals much about the prevailing mind-set towards the female body.

Transnationalism

The transnationalism of modern art enabled analogies with the art of other post-colonial states and with the wider Catholic world to be formed. The cubist artist Mainie Jellett argued that the widespread discernment of Irish art as British could only be overcome by realigning it via modernism to the authentic Irish Celtic art of the pre-colonial period. The ability of modern art to express communal and spiritual values was central to its vindication. In 1942, when the gift of Rouault’s Christ and the Soldier was refused by the Dublin Municipal Gallery of Modern Art (now the Hugh Lane Gallery), its defenders maintained that the work was part of a wider Catholic religious art that was deeply significant to modern Ireland. They referred to the writings of Catholic intellectuals like Jacques Maritain and to medieval religious art to demonstrate that modern European art and Catholic values were compatible with those of the Irish people. In 1956 the painting was accepted into the collection of the Municipal Gallery.

Influential élites in Irish society recognised the necessity of accessing modern art because it represented the height of European culture for much of the twentieth century. This is especially evident in the 1960s, when economic and social changes in Ireland inspired a wider curiosity about international art and culture. Knowledge of modern art provided cultural capital for collectors and the corporate sector, which played a key role in its diffusion. In 1964 the Carroll’s tobacco company initiated the Carroll’s prizes at the Irish Exhibition of Living Art, and leading businessmen Gordon Lambert and Basil Goulding were the major patrons of modern art.

The Troubles in Northern Ireland and the decline of the modern movement internationally precipitated a new period in Irish art in which the broader political contexts and purposes of art-making were increasingly questioned and implicated directly into the artwork. The emerging time-based and conceptual practices differed profoundly from those of earlier forms of art-making, primarily painting, carving and modelling, in Ireland. The latter now seemed overly passive or compliant with the demands of the state. The younger internationalised generation could not see the value of an art practice that negotiated the priorities of the nation state. For this generation, living in a post-structuralist, technological age, it became ‘impossible to defend the terrain of modernism’.

Beckett may have had a point about the ‘Irish people’ not giving a fart about art, but individually many Irish people cared a great deal about it and devoted much time and effort to its promotion and dissemination. Their exertions and their motivations reveal much about modern art and about modern Ireland. The controversies that they provoked prompted debate about the purpose of visual art and about its complex relationship with an indifferent state. For the contemporary reader, they expose the inconsistencies and insecurities that lie at the heart of modern Ireland, and most especially its conflicted attitude towards the value and meaning of art.

Róisín Kennedy lectures in the School of Art History and Cultural Policy at University College Dublin.

Further reading

N. Allen, Modernism, Ireland and Civil War (Cambridge, 2009).

S. Bhreathnach-Lynch, Ireland’s art, Ireland’s history: representing Ireland, 1845 to present (Omaha, 2007).

R. Kennedy, Art and the nation state: the reception of modern art in Ireland (Liverpool, 2021).

D. Lloyd, Beckett’s thing: painting and theatre (Edinburgh, 2016).