By Fiona Fitzsimons

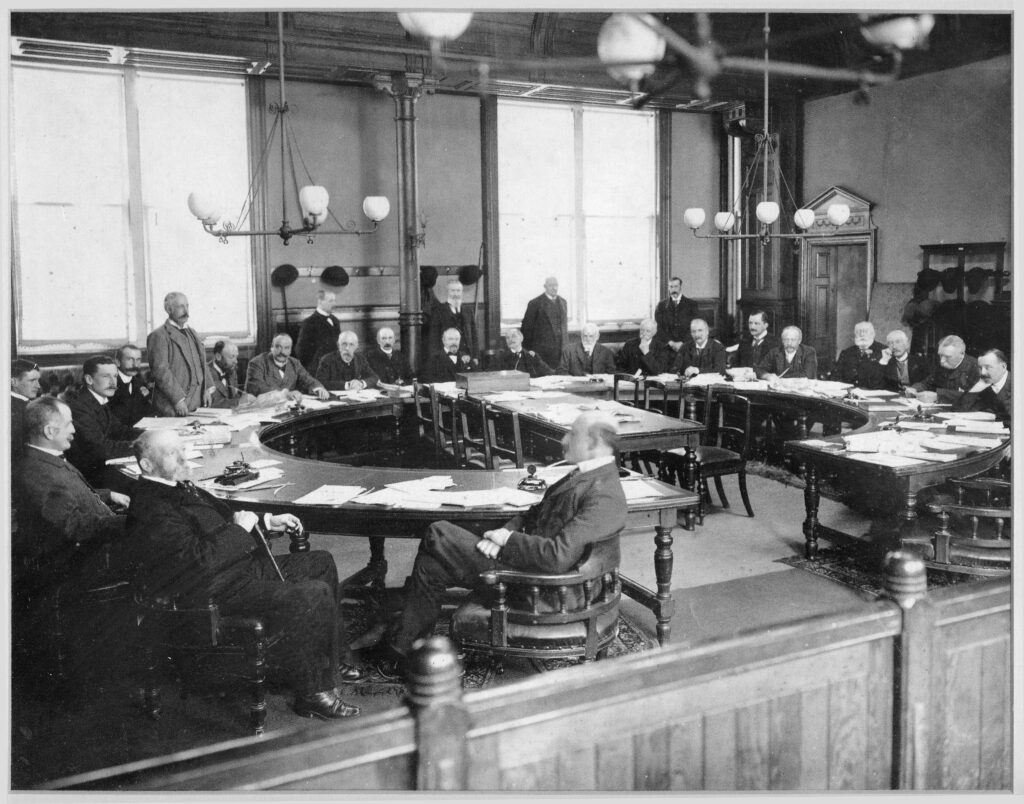

The Anglo-Normans introduced grand juries into Ireland to provide local government in the shired counties. The high sheriff of each county nominated 23 men to the grand jury—as distinct from the ‘petty’ trial jury of twelve—from the largest landowners, excluding peers. Their original role was judicial, deciding on whether cases should proceed to trial.

In 1634 the Irish parliament authorised grand juries to collect the county cess, to pay ‘for building and repairing of bridges and causeways on the king’s highway’. After 1708 their taxing powers extended to the building and repairs of jails and courthouses, and by 1765 county infirmaries. After the Act of Union, grand juries assumed even wider social welfare duties, funding dispensaries (1805), asylums (1817) and fever hospitals (1818). They employed county officials responsible for administration, justice and health.

Growing expenditure drew public criticism. The Grand Jury (Ireland) Act 1836 gave cess-payers some influence through presentment sessions. The Valuation Acts (1826, 1852) replaced cess with a fairer property tax. The structure of local government did not change, however, and the landlord interest remained dominant. The Local Government (Ireland) Act, 1898, transferred administrative and fiscal responsibilities to the new democratically elected county councils.

The Presentments and Query Books list the proposed and approved works. They provide the names of local people (builders, contractors and small traders) in a place at a time, providing sometimes the only evidence for genealogical research. For example, at the spring assizes of 1810, the Louth grand jury paid ‘Turner Macken, Owen and Michael Lennon, [£3] to fill 20 perches of ditches on the turnpike road from Dunleer to Castlebellingham, between the 32 and 33 mile stones’. Payments were also made to Anne Hoey for glazing and to John Hill, slater, for repairs to the roof of Dundalk courthouse, and to James Clarke, carpenter, for repairs to the county gaol.

We find the names of service providers: Jos. Parks, printer, ‘provided paper, and printed 150 copies of the presentments to be distributed’ to invite tenders for work. Charles Connor (Dundalk town cryer) acted as a court interpreter (reminding us that the town’s hinterland was a Gaeltacht until the mid-nineteenth century); Denis Fitzpatrick, carrier, transported prisoners between the courthouse and the gaol; Robert Sibthorpe, apothecary, and William Lee, surgeon, attended to prisoners in the gaol.

We find the names of county officials. In County Louth in 1810, Robert Page was the treasurer and secretary of the county records; Walter Bourne was clerk of the crown; John Bourne was clerk of the peace; Jane Murphy was keeper of Dundalk courthouse; Denis Fitzpatrick was jailer of Dundalk gaol; and the Revd Gervais Tinley was chaplain and inspector of the gaol. Tinley also provided food, fuel, bedding and necessities for prisoners.

The 1810 Books for Louth are particularly detailed and provide the names of the sub-constables appointed in each barony: Thomas Cunningham in Newtown; Bartholomew Eager in Corballis; William Kelly in Louth; Joseph Carty in Castlebellingham; Alexander Pilkington in Rathbody; John Hall in Killincoole; Thomas Lee in Dromiskin; and Joseph Reinhart in Ardpatrick.

By comparing records of earlier years, we can trace continuity and change in local government. We see sub-constables dismissed from their posts for indiscretions: in 1795 John Hill was fired for misconduct; in 1808 Thomas Lynch had £2 deducted ‘for allowing a prisoner in his custody to escape’.

In the 1820s, as the grand jury’s remit widened and the county infrastructure expanded, the records became even more detailed. The 1816 Book runs to 25 pages, while the 1826–8 Book runs to 367. Later books are more structured, arranged by county, barony and parish.

See https://virtualtreasury.ie/backend/flipbooking/the-grand-jury-system-in-Ireland-02/8/.

Fiona Fitzsimons is a director of Eneclann, a Trinity campus company, and of findmypast Ireland.