A mountain of material was written about the Battle of Clontarf in succeeding generations but there is very little that is genuinely contemporaneous; distinguishing between what can be believed and what cannot be believed in later traditions is therefore a tricky business. And the business of deciding once and for all what happened at Clontarf is not helped by the fact that there has been a surprising neglect of analysis of the battle itself by experts in the field. More work needs to be done, and ongoing research will hopefully shed further light. But what is the state of play with current research?

A mountain of material was written about the Battle of Clontarf in succeeding generations but there is very little that is genuinely contemporaneous; distinguishing between what can be believed and what cannot be believed in later traditions is therefore a tricky business. And the business of deciding once and for all what happened at Clontarf is not helped by the fact that there has been a surprising neglect of analysis of the battle itself by experts in the field. More work needs to be done, and ongoing research will hopefully shed further light. But what is the state of play with current research?

Where was it fought?

Many people might be surprised to hear that Clontarf is not mentioned in the early annal accounts of the battle. The earliest certain reference to Clontarf seems to survive in a list of the kings of Munster preserved in the twelfth-century Book of Leinster, which states that Brian was killed in ‘the Battle of Clontarf Weir (Cath Corad Cluana Tarb)’.

Many people might be surprised to hear that Clontarf is not mentioned in the early annal accounts of the battle. The earliest certain reference to Clontarf seems to survive in a list of the kings of Munster preserved in the twelfth-century Book of Leinster, which states that Brian was killed in ‘the Battle of Clontarf Weir (Cath Corad Cluana Tarb)’.

Thus the battle was contested in the immediate environs of this weir. Some think that it was a salmon weir on the River Tolka near Ballybough Bridge. This, however, is not in Clontarf as such. It is pos-sible, therefore, that the weir was not a barrier across the Tolka but was similar to the ancient estuarine fishtraps found, for instance, in the Shannon estuary and Strangford Lough, and one could visualise one of these along the tidal shoreline at Clontarf and between it and Clontarf Island (which survived until the nineteenth century and now forms part of Fairview Park). This is corroborated, I think, by the account elsewhere in the Cogadh Gáedhel re Gallaibh of the death of Brian’s fifteen-year-old grandson Tairdelbach, who ‘went after the Foreigners into the sea [my italics], when the rushing tide wave struck him a blow against the weir of Clontarf (im carrid Cluana Tarb), and so he was drowned’.

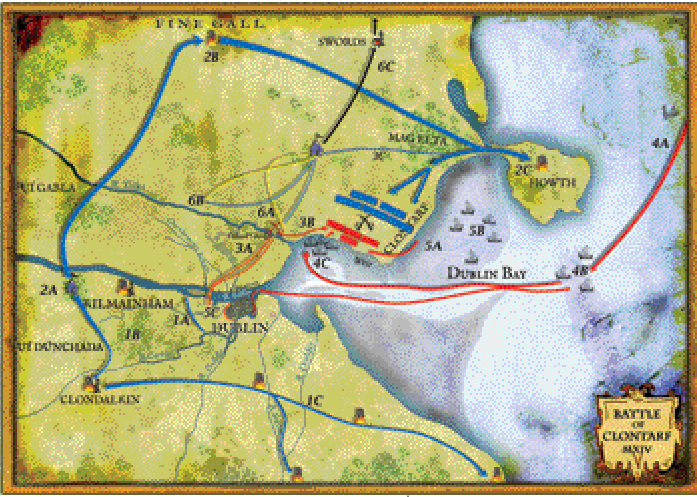

The Cogadh, a work of literature as much as history, is in fact the main source of detail regarding the battle: all we can do is hope that veterans of the battle provided some of it. It asserts that, having reached Dublin, Brian’s forces plundered Fine Gall, north of the Liffey, and when the Foreigners of Dublin saw the area around Howth set ablaze they came into Mag Elta, the coastal plain to which the Howth peninsula attaches, and ‘raised their battle-standards on high’. All the evidence suggests that Brian himself, now in his early 70s, did not take part in the ensuing battle, instead pitching camp out on the Faicthe Átha Cliath, a green area to the west of Dublin often thought to be in the vicinity of Kilmainham.

Meanwhile, the Scandinavian fleet—whose arrival in Dublin is attested to in a variety of sources—was in Dublin Bay, perhaps off the eastern (Fairview) end of Clontarf. These Scandinavians linked up with the Norse of Dublin and the Leinstermen, their vessels having availed of the full tide to make a landing. Battle began at first light and raged all day. But as the tide receded, so it drew the Scandinavian vessels with it and scattered them about the bay. By evening the Norse were compelled to retreat and would have made for the safety of Sitric’s fortress at Dublin or a wood that seems to have stood in the other direction (towards Howth)—not, it appears, the famous Caill Tomair (‘Wood of Thórarr’), a tract of oakwood close to Dublin and highly prized by the Dubliners, but rather a less celebrated grove, apparently to the east of the battle site. The problem for the enemy forces, as they scattered before Brian’s men, was that they could not get to this wood because the incoming tide was between them and it.

Similarly, on the west side of the battlefield Brian’s enemies were slaughtered as they fled: only twenty Dubliners, the Cogadh tells us, escaped, ‘and it was at Dubgall’s Bridge the last of these was killed’. We do not know who Dubgall was or where his bridge was, but he may be Dubgall mac Amlaíb, brother of King Sitric Silkbeard, who commanded the Dublin forces at Clontarf—Sitric himself stayed inside the town to prevent its falling into enemy hands—and perhaps Dubgall is also the man whose estate at Baile Dubgaill gives us Baldoyle. It is generally assumed that his was the bridge over the Liffey (not far from the Four Courts) which separated the town of Dublin from its northern suburb of Oxmantown, then already beginning to take shape. But a more likely location is a bridge straddling the Tolka at Ballybough (which would fit if Dubgall did indeed give his name to Baldoyle, which one reaches to this day by the same route). If this is the case, the Norse needed to reach this bridge and cross over the Tolka to escape to Dublin, but the tide was between them and the bridge.

On the modern landscape, we can imagine the defeated forces being at the old heart of Clontarf—say, between Castle Avenue and Seaview Avenue/Stiles Road—and being pushed downhill towards the sea; to escape to the bridge they would have to traverse what is now Fairview Strand, except that the incoming tide had submerged it. In the other direction, protection was offered by a wooded area, which lay perhaps to the east of Vernon Avenue, but the inundation of the area around Oulton Road and Belgrove Road blocked off that route too, and so they had no option presumably but to position themselves with their backs to the sea and make a stand, which proved disastrous for them, many of them drowning as they were beaten back.

Who was on Brian’s side?

Brian had secured universal acknowledgement of his claim to be king of all Ireland in 1011, but his hegemony had begun to splinter almost immediately. When called upon to serve him militarily on the momentous day, therefore, many of his more reluctant vassals stayed aloof. Not so, however, the man who had preceded him in the high-kingship, Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, king of Tara. His continued commitment to Brian’s cause has been widely doubted and he has been given a very bad press in later literary accounts of Clontarf, but after he entered into Brian’s al-legiance in 1002 there is no evidence that he ever wavered in his duty.

Besides, Brian’s enemies at Clontarf were Máel Sechnaill’s enemies. At the start of that fateful year, 1014, Sitric of Dublin and the king of Leinster, Máelmórda mac Murchada, had attacked Máel Sechnaill’s kingdom of Mide, obviously considering him as much an enemy as Brian. Furthermore, a near-contemporary text listing the kings of Ireland tells us that Máel Sechnaill fought in 25 battles, including two battles at Dublin, presumably the great battle of Glenn Máma in 999 and Clontarf in 1014.

The casualty list shows that Brian had further wide-ranging support. The Munster contingent in his army included erstwhile enemies like the Eóganacht kings of Loch Léin (the Killarney area) and Fer Maige (around Fermoy), both of whom lost their lives alongside Brian, as did Mothla ua Fáeláin, king of the Déisi Muman, a people who had been slow to rally to his cause. And at least two more Munster kings—the west Munster king of Ciarraige Luachra and the king of the County Clare people called Corco Baiscind—also fell with Brian.

And his support extended into Leth Cuinn (the Northern Half). Not only did Brian have the support of its most senior royal, the king of Tara himself, but a number of Connacht kings died fighting for his cause, including Ua Cellaig of Uí Maine and Ua hEidin of Uí Fiachrach Aidni. If these Connacht kings died, we must assume that there were others present who survived, and that means that the geographical spread was not inconsiderable. So significant was the compass of support, in fact, that a certain Domnall mac Eimein mic Cainnich, earl of Mar in Scotland, also perished alongside Brian.

Why did the battle take place?

King Sitric’s ambitions are the key to understanding the battle’s significance. His father, Amlaíbh Cuarán, had been one of the great figures throughout the archipelago in the tenth century who at various points held power in Dublin and its hinterland, in York and Northumbria, and probably also in Man and the Isles. It has been argued that Amlaíbh sought the kingship of Tara until he was defeated in battle there in 980. His son Sitric, too, had been defeated by Brian at Glenn Máma in 999, a humiliation that meant that the Dubliners had to tolerate Munster domination until such time as an opportunity came to break free.

That opportunity came in 1013 amidst the upheaval of the Danish conquest of England by the family of King Knut, when change was in the air, when unparalleled numbers of Scandinavian and Insular troops and warships were at hand, battle-ready and confident of the new possibilities. These are the men—behind the famous raven banner of Jarl Sigurd, manning the vessels of Bródar—whom Sitric of Dublin recruited to his cause and who lined up on the shores of Dublin Bay in April 2014 to take on his Munster oppressor (as Brian must have appeared).

There is no telling, at this remove, precisely what they hoped to achieve but, if England could be conquered, Ireland surely seemed a sitting duck. And the question that was asked of Brian on that Good Friday was whether he would crumple as had his contemporary, Ethelred the Unready, in the face of King Knut’s father, Sveinn Forkbeard of Denmark, the previous summer. That Brian did not was his claim to fame, augmented by the fact that he gave his own life to the task.

Seán Duffy is Associate Professor of Medieval History at Trinity College, Dublin.

Read More: When was it fought?

Who opposed Brian?

Further reading

C. Downham, ‘The Battle of Clontarf in Irish history and legend’, History Ireland 13 (5) (Sept./Oct. 2005), 19–23.

S. Duffy, Brian Boru and the Battle of Clontarf (Dublin, 2013).

M. Ní Mhaonaigh, Brian Boru: Ireland’s greatest king? (Stroud, 2008).