In Ireland, public meetings are absolutely necessary preliminaries to any enterprise … The hard-headed, commercially-minded Ulsterman is just as fond of public meetings as the Connacht Celt. He would hold them with drums and full-dress speechifying, even if he were organising a secret society and arranging for a rebellion. George A. Birmingham, General John Regan (1912) by Gary Owens

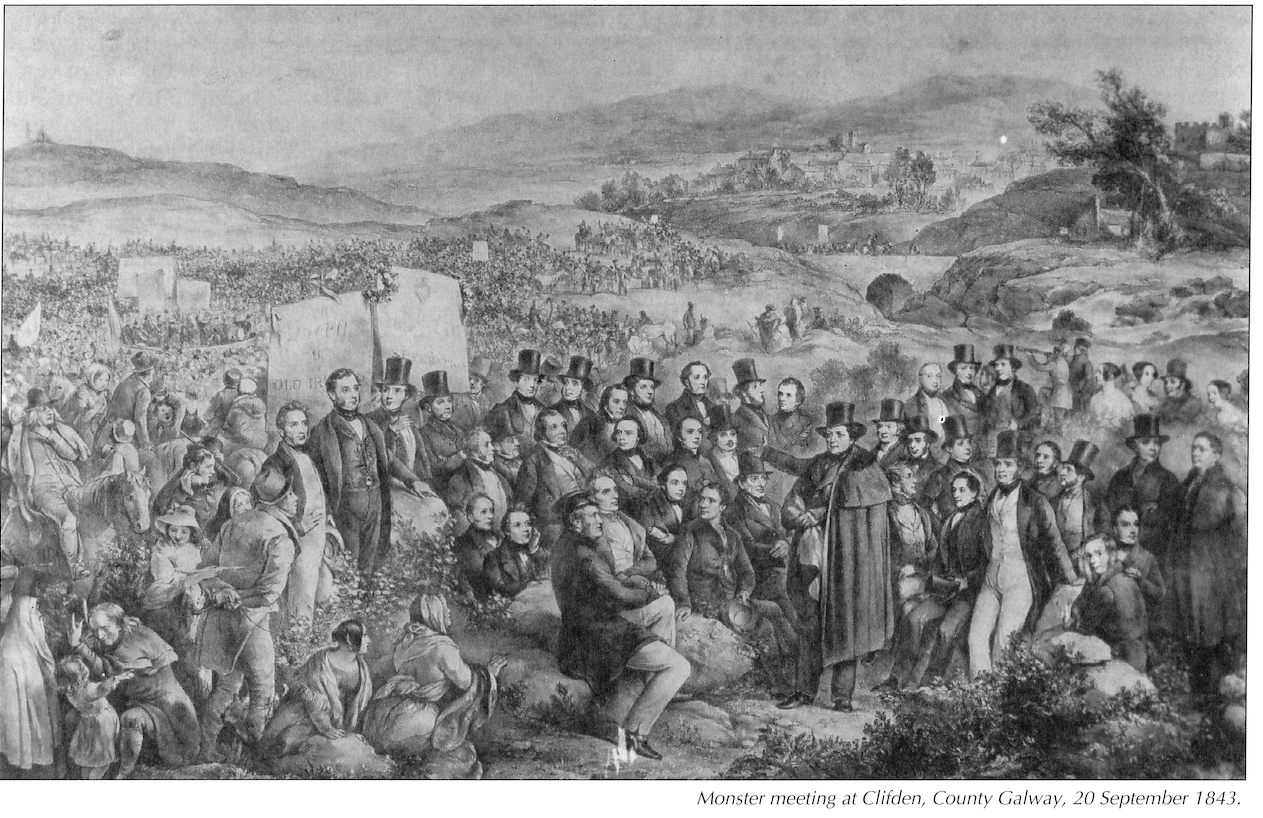

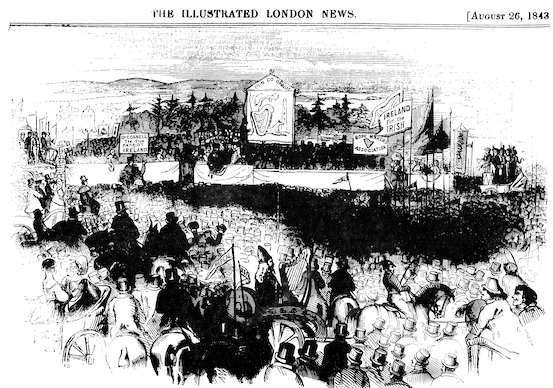

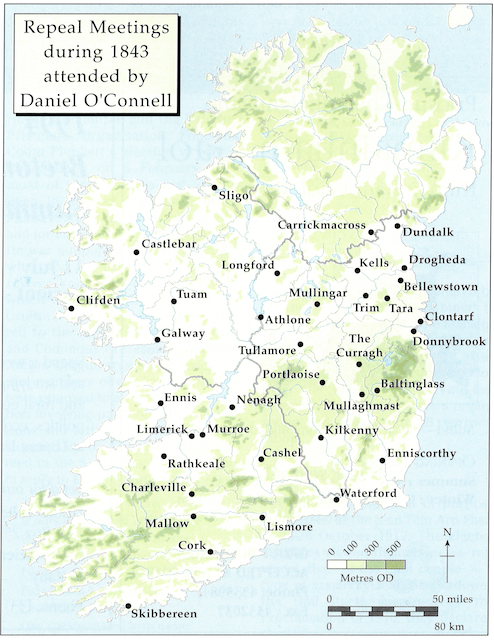

Birmingham’s observation, for all its condescending glibness, reflects an apparent truth about Irish culture. Assembling and marching in large numbers has been a cherished and familiar form of political expression for centuries. The most spectacular public gatherings in Irish history were the more than fifty-plus ‘monster meetings’ held across the three southern provinces during the summers of 1843 and 1845 to demonstrate support for Daniel O’Connell’s campaign to repeal the Act of Union. These gatherings were arguably the largest mass phenomena in modern Irish history. In the contemporary nationalist press, almost all of them were said to number over 100,000; many were reported at between a quarter million and a half million; and one of them, the famous gathering at Tara Hill in mid-August 1843, was put at over one million. But the meetings were remarkable for more than their reputed size. Above all, they helped to politicise a large portion of Irish society. They were, to use Donal McCartney’s apt metaphor, ‘hedge schools in which the masses were educated into the nationalist politics of repeal’. As every teacher knows, however, the process of education is often complex and it can take many forms. This was certainly true of the monster meetings.

Repeal membership card

Symbols and ritual performances

Nor should we conclude that, because many people did not or could not listen to the speeches, they were somehow excluded from the process of politicisation that the monster meetings were designed to promote. Equally important were symbolic displays and ritual performances that everyone who was present could witness or take part in and, above all, comprehend. Symbolism and ritual help to explain what is otherwise inexplicable: they suggest how political communication could take place among tens of thousands in the vast setting of a monster meeting. Seen from the crowd, O’Connell standing atop a speaker’s platform was himself a symbol, part of the entire mise en scene along with banners, emblems, costumed bands, decorated vehicles and other adornments. Not everyone could hear him, but they could at least see him and he often added to the spectacle with visual flourishes that were calculated to impress. He appeared at many meetings in a specially-designed green repeal cap or ‘Cap of Liberty’, removing it, waving it, or clapping it on his head as occasion demanded.

Moving forests, moving hearts

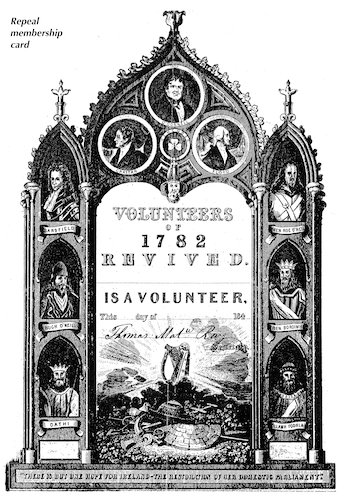

No one who saw displays and performances such as these – and there were many like them – could mistake their political messages. Most of them were unambiguous and easily deciphered. There were other visual devices and ritual performances, however, whose meanings were more deeply hidden. They were multi-vocal in expression and sometimes required specific knowledge to decode them. Demonstrators had ways of saying things symbolically to their immediate audiences – sometimes subversive things – that could be unintelligible to anyone ignorant of their cultural context. A good example was their use of plants. Evergreen, laurel and other greenery were widely used to decorate meetings and demonstrations throughout Britain and Ireland during the nineteenth century. They were abundant, inexpensive, pleasing to the eye and adaptable to scores of uses. In Ireland during the repeal campaigns of the 1840s they adorned streets, houses, parade floats and even people. Above all, Irish people liked to carry boughs, branches and sometimes whole trees as they marched in processions. Newspaper accounts typically described monster meeting parades as presenting the appearance of ‘moving forests’. Throughout Europe, certain plants were accepted emblems of specific qualities: laurels represented amity, peace and regeneration; yew branches signified endurance and constancy. But in Ireland, plant symbolism operated on other levels. According to the Party Processions Act of 1832, it was unlawful for anyone who took part in public demonstrations in Ireland to ‘bear, wear, or have amongst them … any Banner, Emblem, Flag, or Symbol’ that might provoke sectarian animosity. Consequently,green flags and political banners were banned from repeal processions. Despite their prohibition, however, banners and flags did appear, albeit in disguised form. When thousands of marchers paraded with green boughs, bushes and whole trees, they were symbolically brandishing nationalist emblems and, at the same time, cleverly evading the law. Like their counterparts elsewhere in Europe at this time who used animal blood, red carnations, scarlet pins, buttons and other everyday materials in public demonstrations to display sympathy with outlawed socialist groups, Irish men and women used the greenery that was everywhere around them to create substitute national flags . The symbolic meaning of plants did not end there. Most of the branches, trees and bushes that people brought to the demonstrations had to be taken from private lands; in many, if not most instances, these were the demesnes and plantations of wealthy landowners, and this charged them with another powerful meaning. Carried proudly in processions, they immediately became symbolic spoils of battle, victory trophies in the conflict between the dominant and subordinated. As the monster meetings grew in size, organisers worried that the triumphal display of greenery was needlessly provocative and that stealing plants would lead to violence. For this reason, repeal leaders urged people to attend the gatherings without so much as a bough or a twig that would betoken injury to the property of the aristocracy. Such orders brought an end to repeal processions that resembled ‘moving forests’, but the parades continued to be a source of provocative visual messages. Each group of tradesmen who marched in the Ennis procession was preceded by one of their number who bore above his head a loaf of bread on a pole to denote poverty and, by implication, an indictment of British misrule. In dozens of other processions, thousands of people displayed their repeal membership cards on the ends of sticks or white wands or they tied them to their hats, coats or necks by green ribbons. The six-bynine inch cards, each of them displaying a pantheon of ancient and modern Irish heroes and proudly bearing the name of their owner, were prized commodities among repeal supporters. Exhibiting them publicly in processions bestowed on their holders a sense of pride, individuality and empowerment. In this regard the cards were invested with talismanic qualities similar to those of scapulars worn by the devout. At the same time they acted as ersatz political banners and, as such, they betokened a subtle evasion of the law.

The parade as theatre

The symbolic language of processions was not confined to mobile displays and decorations. The very structure of parades – the way that participants arranged themselves in a particular order of march and the routes they followed – constituted a kind of symbolic vocabulary. Public processions were, to use Robert Darnton’s phrase, ‘a statement unfurled in the streets’, through which a community represented itself to itself and to the outside world. Their structure also constituted a symbolic declaration of political beliefs that underscored the countless other visual and verbal messages that swirled through every stage of a monster meeting. A uniformed band or a body of horsemen formed the head of a typical procession and behind them came the local trades bodies, each with its distinguishing banners, floats and uniforms. They were followed by repeal clubs, temperance groups and fraternal organisations. Temperance bands from outlying towns were scattered among them. Then came the public at large, most of them on foot but many on horseback or in farm carts, accompanied by scores of parish clergy. At the appointed time, the cortege noisily marched off to meet the Liberator at a pre-arranged rendezvous a few miles outside the town. Leaving separately, either before or after the main body of the parade, were local officials and other dignitaries in carriages. After these groups ceremonially greeted O’Connell at a pre-arranged point of rendezvous, the processionre-formed into a different configuration for the march back through the town to the meeting ground. As before, the trades, temperance and volunteer bodies led the cavalcade, but they were now joined by the town magistrates and other notables who formed up immediately behind them. O’Connell usually took his place somewhere in the midst of the dignitaries or at their rear. Trailing off behind the Liberator’s carriage came the great bulk of the citizenry.

Processions as texts

The procession constituted a text that could be read in two ways simultaneously. First, it was a caricature of a community’s social structure. Beginning with the trades bodies and running upwards through middle class groups to the civic and clerical hierarchy, it culminated in the imposing figure of O’Connell riding atop a special float or in his carriage pulled by four horses. He formed the symbolic centre of every procession, the peak of a moving status pyramid before whom marched ascending ranks of labourers, artisans and representatives of the middle classesand behind whom followed a relatively unstructured mass of town and country folk. O’Connell was the unifying element in a repeal procession, and that was the second way that a parade could be read. Invariably, two groups marched out separately from a town to greet the Liberator: trades bodies, townsfolk and country people on the one hand and local dignitaries on the other. When they returned, it was as a unified body with O’Connell forming their central nucleus and fusing the components of the community which were hitherto separated. In this way, the procession became a visual metaphor of the way in which O’Connell had unified the urban middle classes and tenant farmers under the banner of repeal during the previous decade. This image acquired deeper meaning, not to mention emotional power, through its close resemblance to familiar ritual forms in the Catholic church. O’Connell’s symbolic function was not unlike that of a saint’s image or the Host carried in religious processions. As in those ceremonies, the unifying object brought together disparate elements in the community: O’Connell symbolicallysymbolically joined rich and poor, clergy and laity, magistrates and people, participants and spectators. The repeal monster meetings allowed hundreds of thousands of people the opportunity to communicate political ideas among themselves in a variety of ways. In these hedge-schools of nationalism, the distinction between teachers and pupils was not always clear.

Gary Owens is an Associate Professor of History at Huron College, the University of Western Ontario.

Further reading:

O. MacDonagh, The Emancipist: Daniel O’Connell 1830-47 (London 1989). G. Owens, ‘Constructing the Repeal Spectacle’ in M. R. O’Connell (ed.), People Power (Dublin 1993). G. Owens, ‘Nationalism Without Words’ in J. Donnelly and K. Miller (eds.), Popular Culture in Pre-Famine Ireland (forthcoming).