by Niall Ó Ciosáin

There was a time when Irish boys were free to choose their own school readers … being sturdy lads, born into a heritage of suffering and persecution, the spirit of resistance burning in their veins, it is not surprising that the reading book they liked best was a cheap little work containing an account of the daring deeds of famous Irish outlaws, rapparees and highwaymen.

Introduction to ‘Highwaymen in Irish History’ (Our Boys 7937)

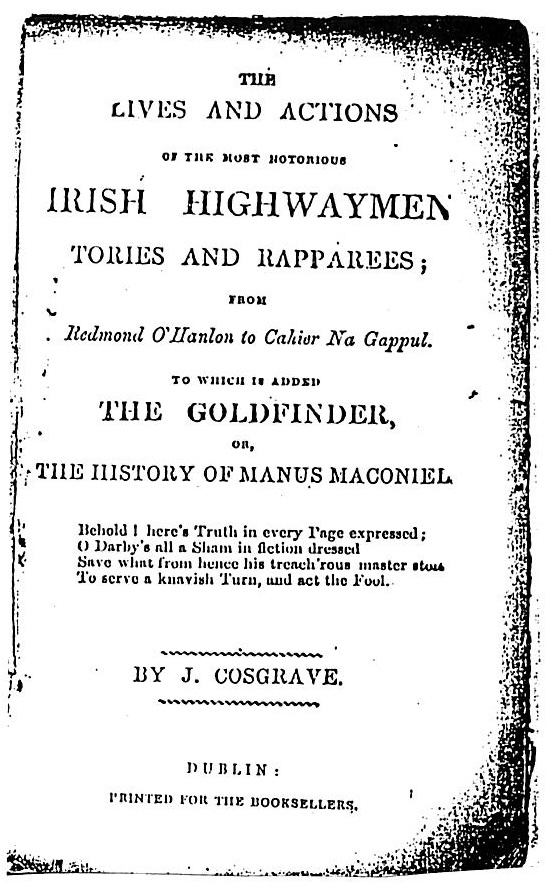

Who were these outlaws and what was this popular book? Criminal biography was one of the standard genres of popular literature in eighteenth and nineteenth-century Europe and a frequent item among the small books sold by travelling pedlars and shops in rural areas. Our Boys was referring to the main Irish example of the genre, The Lives and Actions of the Most Notorious Irish Highwaymen, Tories and Rapparees. The book was first printed in the mid-eighteenth century and had very frequent reprints at a low price; in the early nineteenth-century it could be bought for threepence at a time when a newspaper cost four or five pence.

Although the criminals described in the book were all based on real figures, mostly from the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, their stories are largely fictionalised. They are presented as ‘noble robbers’ of genteel extraction, robbing the rich to give to the poor, and supported by the people. This sort of figure is common in European folklore. As a literary figure, however, the highwayman or robber has other textual origins whose examination will explain the particular form taken by the figures in Irish Highwaymen.

Criminal countercultures

Before the eighteenth century, criminality was dealt with in literary form in a number of ways. First, there were texts which attempted to represent within ‘official’ culture those who were outside or marginal to it. This originated in discussions of the poor and beggars in the sixteenth century and was extended to other groups, including criminals, in the seventeenth. It represented these groups as ‘countercultures’ whose organisation parallelled or was an inversion of conventional society. Thus beggars or robbers were shown as forming organised hierarchies, with a leader, such as the ‘king of the beggars’; with their own rules, rituals and laws, and frequently featuring an alternative language such as beggars’ cant or thieves’ slang. A Caveat or Warning for Common Cursetors, vulgarly called vagabonds (1566), to take one example, explains the tricks and cheats used by thieves, beggars, card- sharpers and the like. These books were read partly as explanations and classifications of groups which were on the margins of society, partly as practical guides to dealing with them. From this tradition, criminal biography derived the motif of the robber band — a leader, lieutenants, captains and so on, organised like an alternative government — as well as minute descriptions of particular tricks. As an example of the latter, Irish Highwaymen includes the life of Charles Dempsey, ‘Cahier na gcoppul’, a horse thief, and lists many of his methods of operation.

Loveable villains

If the classification literature presents a static picture of crime, the second source supplies a narrative dimension focussing on an individual robber — the picaresque novel, also a genre of sixteenth and seventeenth-century origin. It follows the adventures of a rogue, presented sympathetically as a loveable villain, through an episodic series of tricks and frauds perpetrated on others. The keyword of the picaresque was ‘rogue’ — texts frequently had titles like The English Rogue — and the connection was clear to readers of Irish Highwaymen which was commonly known as ‘Irish Rogues’.

‘Last speeches‘

The third sOurce come from the actual historical figures to whose names the stories are attached — the practice of printing the ‘last speeches’ of condemned criminals before death, detailing their crimes and professing repentance. These texts, usually single sheets, were generally sold round the scaffold to provide a written counterpart to the public ritual of seventeenth and eighteenthcentury execution.

In early eighteenth-century England, the three strands were combined to produce large collections of criminal lives, such as The Complete History of the Lives and Robberies of the most notorious Highwaymen by Alexander Smith, first published in London in 1714. This and similar books were best-sellers in their day. Irish Highwaymen was clearly intended to be their Irish equivalent, even taking some of its characters from Smith’s book. The characters in Irish Highwaymen, therefore, although based on actual historical figures, are presented in a highly stylised way: some of the crimes are told factually, some roguish stories are added, in which the robber tricks his victims, and many of the figures have followers and power structures of their own.

This genealogy explains how the texts took the shape they did, and it suggests their possible attraction for the better-off reader, keen to understand crime by classifying it and to become aware of robbers’ methods. It does not entirely explain the continuing appeal of the book to less privileged readers. It was probably due to the more favourable view of the noble robber in folklore, which would have influenced the style of reading amongst a popular audience, picking out, for example, the more sympathetic elements deriving from the picaresque

Traditional morality in conflict with the state

The noble robber had a particular resonance in the period in which Irish Highwaymen was read. One of the main targets of its characters is authority and the state, and favourite victims are soldiers and tax collectors. The eighteenth and nineteenth were the centuries in which the ordinary reader came into continuous contact with state agencies for the first time, whether paying tax or appearing in court. The criminal biography frequently presents key moments in which a traditional morality comes into conflict with state law and order agencies. Take for example the beginning of the life of Paul Liddy, ‘a gentleman robber’:

Paul Liddy was born in Munster, of very reputable parents, who had him educated after a genteel manner, by the best masters in the country … But before he had well arrived at man’s estate, it happened very unluckily for him, that a kinsman of his was taken by the sheriff of the county, upon an execution for a debt … Paul and his brother having notice thereof…came with assistance to the rescue of his relation, whom they carried away from the bailiffs by force, but in the conflict one of the sheriff’s servants happened to be killed … whereupon warrants upon warrants were issued out after the rescuers, and great rewards offered for taking the leaders.

Liddy kills the sheriff’s servant by putting kinship loyalty before the law, a classic instance of such a conflict. The robber represents traditional values in being the head of a power structure alternative to that of the state and which has popular support. In other words, the motif of the ‘underworld’ paralleling the conventional world has now acquired a life of its own. lt has become at the same time a legitimising feature of crime and a parody of official structures. This is clear in the life of Redmond O’Hanlon, the first character in Irish Highwaymen:

In imitation of Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth, [Redmond O’Hanlon] took upon himself the title of Protector of the Rights and Properties of his Benefactors and Contributors, and Chief Ranger of the Mountains, Surveyor-General of all the high roads of Ireland, Lord Examiner of all passengers, committing such villainies and barbarities on sturdy travellers, as he called them, as were never heard of before, driving away whole herds of cattle from such as were in contempt of his protection and authority had given him offence by running in arrears, though he seldom used anyone ill that did not oppose him. Yet he seldom robbed a poor man, but on the contrary was always generous to those in necessity and distress.

Often the chief robber is the head of this structure by virtue of his high social position — he is noble in blood as well as in deed. The classic English case is Robin Hood, who in many versions of the story is the unjustly outlawed Duke of Huntington. In a similar vein, O’Hanlon came from an old landed family in County Armagh.

Moral legitimacy derived from dispossessed aristocracy

In the Irish case, the implications of the nobility of the robber are striking. Some of the characters in Irish Highwaymen are connected in various ways to the old Catholic aristocracy, which was broken in the seventeenth century. O’Hanlon is described as coming from one of the ‘Irish families who had a hand in the wars of Ireland, were dispossessed, and their lands forfeited’. The moral legitimacy of the bandit hero in Ireland, therefore, derives partly or mainly from genealogical continuity with a dispossessed aristocracy. This would have been clear to readers, not only from the lives themselves, but also from the title of the book. ‘Tories’ were ‘Tóraithe’, literally ‘wanted’ outlaws in the period following the wars of the 1640s and 1689-91, dispossessed landowners and evicted tenants remaining in their areas as bandits.

Influence on popular political thought

Given this powerful political undercurrent in Irish Highwaymen, the text is of importance within the history of popular political thought in Ireland. By the 1790s the feeling of dispossession, initially aristocratic, became more generalised among sections of the rural population, sometimes among all those who shared the surname of the original landowner. When or how this generalisation occurred is not clear; Gaelic poetry was probably one vehicle of the ideology, criminal biography in English another.

In the nineteenth century, within popular Catholic nationalist politics,there was clearly a use for figures who embodied an anti-state and antilandlord ideology, and the highwaymen were reconstituted as protonationalists, fighting the British state and landlordism. This necessitated a semantic shift — the original title mentions Highwaymen, Tories and Rapparees, but the word ‘Tory’ was clearly inappropriate and even awkward by the nineteenth century since it had taken on its present meaning within British politics. There was therefore a shift towards replacing it with ‘Rapparees’, and these became a stock figure of later nationalist poetry and novels. Charles Gavan Duffy, the Young Irelander, provides an early case in a ballad called The Rapparees:

Now Sassenach and Cromweller, take heed of what I say,

Keep down your black and angry looks that scorn us night and day;

For there’s a just and wrathful Judge that every action sees,

And He’ll make strong, to right our wrong, the faithful Rapparees.

One could multiply examples from the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and it was within this context that Our Boys presented its highwaymen as nationalist figures. By this time, the highwaymen had been through a number of literary transformations and bore little resemblance to the historical figures on which they were ostensibly based.

Niall Ó Ciosáin lectures in history at University College Galway.

Further reading:

E.G. Hobsbawn, Bandits (Harmondsworth 1969).

L.B. Falaler, Turned to Account: the forms and functions of criminal biography in eighteenth-century England (Cambridge 1987).

R. Chartier, ‘The literature of roguery in the Bibliotheque Bleue’ in R. Chartier (ed.), The cultural uses of print in early modern France (Princeton 1987).