With the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1921, with its subsequent ratification in Dáil Éireann on 7 January 1922, and with the establishment of a Provisional Government of the Irish Free State, responsibility for the administration of education in southern Ireland passed to it on 1 February 1922. Because political independence had followed upon a cultural revolution, of which the main driving force was the Gaelic League, it was almost inevitable that the political ethos of the new state would reflect the Gaelic mode. Accordingly, the forces of the new state were directed towards the recreation of that Gaelic society which had begun to fall apart after the battle of Kinsale in 1601, and which had largely disappeared by the end of the nineteenth century. But now with the apparatus of state in the hands of a native government, the education system was seen as an instrument for the achievement of that objective.

Pride and self-respect

Already, in anticipation of some form of native government being established, the Irish National Teachers’ Organisation (INTO) at its annual congress at Easter 1920, had directed its executive to convene a representative conference in order to frame a programme in accordance with Irish ideals and conditions. This First National Programme for Primary Schools was adopted by the government in April 1922 and issued to primary schools. The role of history was to foster a sense of national identity, pride and self-respect, taught through the medium of Irish, by demonstrating that the Irish race had fulfilled a great mission in the advancement of civilisation. Thus, both the Irish language and Irish history were to be interwoven in the twin aims of creating a Gaelic state and of legitimising that state through the appeal to history.

The history programme laid down that in third class the child should be introduced to the stories and legends of Ireland, with special reference to local history. Formal history was to commence in fourth class. Here the child would be introduced to the outstanding personages of Irish history. Commencing with Cormac Mac Art, Saint Patrick, and Saint Columcille, it would range over the centuries to conclude with Sarsfield, Wolfe Tone and O’Connell. In this manner, the child would be imbued with a heroic notion of Irish history and would learn of the contribution of successive Irish people over a wide range of human endeavour—religion, missionary activity, military and political leadership.

For fifth class the course laid down was a general outline of the history of Ireland from Saint Patrick to the Act of Union, while the course for sixth class was the history of Ireland from the Treaty of Limerick to the present, with special reference to the land question. In addition, the sixth class course included the historic connection between Ireland and England, Scotland, America, France, Spain, and Australia, together with lessons in citizenship. The educational aim of the government was stated as ‘the strengthening of the national fibre by giving the language, history, music and tradition of Ireland their natural place in the life of the schools’.

Clash with reality

Although these high ideals met with general approval, they soon began to clash with reality, especially in the area of teaching subjects through Irish. Accordingly, the Minister for Education, Eoin McNeill, convened a Second Programme conference which presented its report in March 1926. The report endorsed the programme of 1922 but accepted that a more gradual and realistic approach was necessary. It made allowance for teachers not sufficiently competent to teach subjects through Irish and also it lightened the requirements in history. The existing programme was seen as beginning at too early a time in the child’s development and also as being too comprehensive in character. Accordingly, it prescribed the formal teaching of history as an obligatory subject to begin in fifth class and recommended that for third and fourth classes teachers should choose ‘readers that contained accounts of important personages and striking incidents in our national history’. The 1926 programme for fifth and sixth class retained the idea of an outline chronological treatment of Irish history from the earliest times to the Treaty of 1921. It recommended that the periods of history that were more inspiring and better calculated to lead to pride of country should be specially dwelt upon. Moreover, the period after the Act of Union was to be seen as the story of the Irish people struggling on several fronts—political, religious, linguistic and economic—and eventually coming into its heritage with the establishment of native government, under which the Gaelic state could once again be recreated.

Creating a patriotic and Gaelic-speaking people

With the advent of a new administration under Fianna Fáil in February 1932, there commenced a renewed emphasis on the ideal of establishing a Gaelic-speaking nation through the instrument of education. The Minister for Education, Thomas Derrig, was convinced of the desirability and practicality of creating a patriotic and Gaelic-speaking people and that Irish history had a central role to play in the process. Speaking in the Dáil 27 October 1932, he declared that pupils were not taking a sufficient interest in the Irish language because teachers were not sufficiently utilising the history of Ireland to arouse the pride and spirit of the people. If through the teaching of Irish history, a patriotic love of country could be cultivated, then the pupils would be inspired to learn the language, and the work of Gaelicising Ireland could be achieved.

According to this policy, the ultimate goal was the establishment of a Gaelic Ireland: this was to be achieved by reviving the Irish language, while the role of history was to inspire the pupils with a love of all things Irish. Thus the teaching of the Irish language and of Irish history would conspire together not only to make Irish speakers of the children but also to ensure the cultural continuity of the nation by putting its youth in possession of the language, history and traditions of the Irish people, thus fixing its outlook in the Gaelic mode.

Secondary level

On 1 August 1924 the Intermediate Examination system was abolished. It was replaced with two new certificate examinations: the Intermediate and the Leaving. At Intermediate level, history and geography became a core compulsory subject. In history the prescribed course was (a), a general outline of Irish history and of the historical relations of Ireland with Britain and the continents of Europe, America and Australia; and (b), a general outline of the history of Western Europe since the dissolution of the Roman Empire. At Leaving Certificate level, a more detailed knowledge of the Intermediate course was laid down, together with an intensive course in any one of eight options. These included two options of social, economic and cultural history of periods in Irish history, and one on the development of national industries in Europe with special reference to small countries such as Belgium, Denmark and Switzerland.

The proscription of a full outline course of Irish history in its own right, and the non-recognition of British and Empire history, was in full accord with the state policy of employing education, and history within it, to create an ‘Irish Ireland’. Moreover, the fact that Irish history had been ignored under the National Board and neglected under the Intermediate Board, and that this had been interpreted as a deliberate policy of anglicisation, now served to reinforce the belief that ipso facto the promotion of Irish history would serve the policy of gaelicisation. However, it must be emphasised that the role of history in the policy of gaelicisation was chiefly centred on the national school and only to a very modest degree on the secondary school. This stemmed from the realisation that it was more efficacious to commence at the younger age level, and from the fact that secondary schools were exclusively in private denominational hands catering for a relatively small proportion of pupils.

A branch of religious instruction

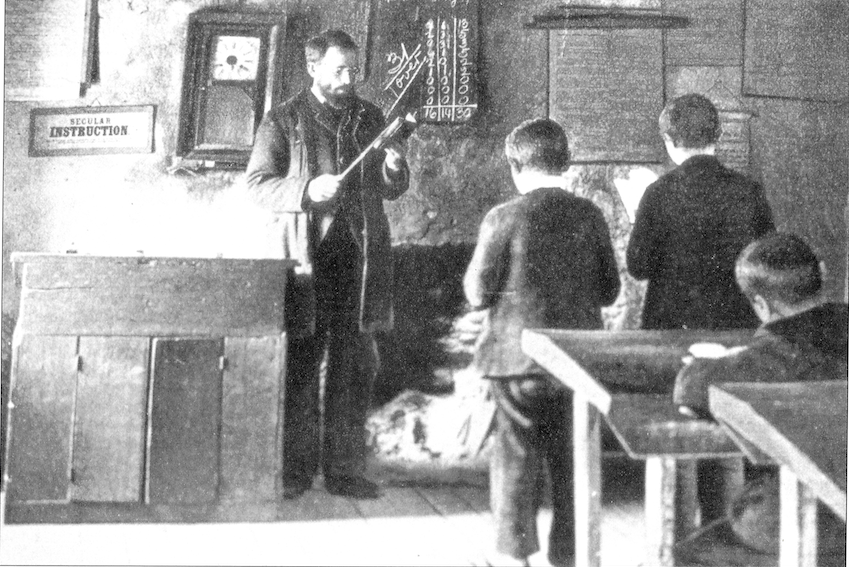

Yet a deeper understanding of the role of history at secondary level may be obtained from admissions made by one of its chief architects: Professor of Education at University College Dublin, T.M. Corcoran SJ, who played a most influential role in the formulation of educational policy during the formative years of the Irish Free State. Corcoran did not accept that history was a subject of secular instruction: he clearly and unequivocally saw history as a branch of religious instruction, of ethics, of Catholic sociology, and held that through the teaching of history, Catholic principles could find an entrance into the substance of other subjects. He declared that the programme of studies in history was framed on a certain plan aimed at reversing English ideas of historical studies, which were held to be ‘inimical to the study of the work and development of the Church of Christ’.

Concurrently national and universal

Under the old Intermediate Board, the English idea of historical studies meant that up to the age of sixteen the main concern was with British history. Only at seventeen and eighteen were they allowed to contemplate Europe, but even then, care was taken, in both programme and examination, that Europe would be viewed through Great Britain. The new history programme was founded on the view that since the study of the action of the Catholic Church on the world and on human progress and culture was essentially both national and universal (but primarily by its aim and mission, universal) the structured plan for history should conform to a similar vision of at once being both national and universal. Accordingly, the previous plan of history spiralling upwards from its base in English history and gradually outwards into Europe (though still filtered through the English prism), gave way in the new programme to the concept of history as at once broad and universal, while also concurrently national. Irish history and European history were placed side by side in the new history programme.

Concerning the eight intensive courses on selected topics from which pupils had to study one, the two epochs on Irish history were seen as having ‘countless direct connections with the core and centre of all Catholic education’. The option on ancient history was ‘excellently suited for the school where Latin and Greek are given pride of place’. Options on the medieval and renaissance periods were considered ‘fine cultural topics, rich also in moral and religious lessons and ideal for selection by girls’ schools’. The option on European architecture was ‘an apt branch of study for a diocesan or missionary school’, while the option on the development of national industries with reference to small countries was an attempt to employ history as a means of fostering national self-confidence in the ability of the new state to emulate the achievements of Belgium, Denmark and Switzerland.

The intended role of history in secondary schools was to provide varied channels of education in moral principles and for moral action by emphasising that in any historical event it was the moral issue that really mattered. In this way, the teaching of Catholic principles could be run along the track of the history programme. This adjustment of the plan of history, in accordance with the national and universal dimensions of the Catholic Church, saw its role ultimately as producing citizens who would not fear to be explicitly Catholic in the field of social action, and who would not shirk the use of moral decisions on the facts of public life.

Conclusion

At primary level, the onus placed upon history was a daunting one. At one level its study was intended to foster a sense of national consciousness and pride. At another but related level, through the study of Irish history the pupils would come to appreciate the importance of the Irish language as a bulwark against the decline of national consciousness. Thus an appeal to history would legitimise the restoration of Irish as the spoken language of the people. At secondary level, the nationalist role ascribed to history in primary schools, was far less apparent. Moreover, since practically all secondary schools were owned and administered by religious orders and staffed by its members, it followed that a Catholic world-view would permeate the role of history in secondary education.

Francis T. Holohan teaches history at Rockford Manor, Blackrock, County Dublin.

Further reading:

Coolahan, Irish Education History and Structure (Dublin 1981).

National Programme of Primary Instruction (Dublin 1922).

Report and Programme presented by the National Programme Conference to the Minister for Education (Dublin 1926).

Dept. of Education, Notes for Teachers: History (Dublin 1933).