Directed by Kevin Costner

By David Murphy

Fans of Kevin Costner will be well aware of his fascination with the Western movie formula. To date, he has made several forays into this genre as an actor, and also in the roles of producer and/or director. Previous Westerns have included Silverado (1985), Open Range (2003) and the epic Dances with Wolves (1990), and he has played a major role in the modern Western phenomenon that is Yellowstone. Costner’s latest Western project, Horizon: an American Saga, is truly epic in film-making terms, and this first instalment alone runs to three hours. This has been a long-term project for Costner, who is fascinated by the history of the American frontier and is a frequent contributor to discussions on this subject. He is a co-writer of Horizon, along with Jon Baird and Mark Kasdan, and he and Kasdan are co-producers. Ultimately, a series of films is envisaged and, such is Costner’s commitment to Horizon, he is stepping down from his role in Yellowstone to focus on what he clearly sees as a legacy project.

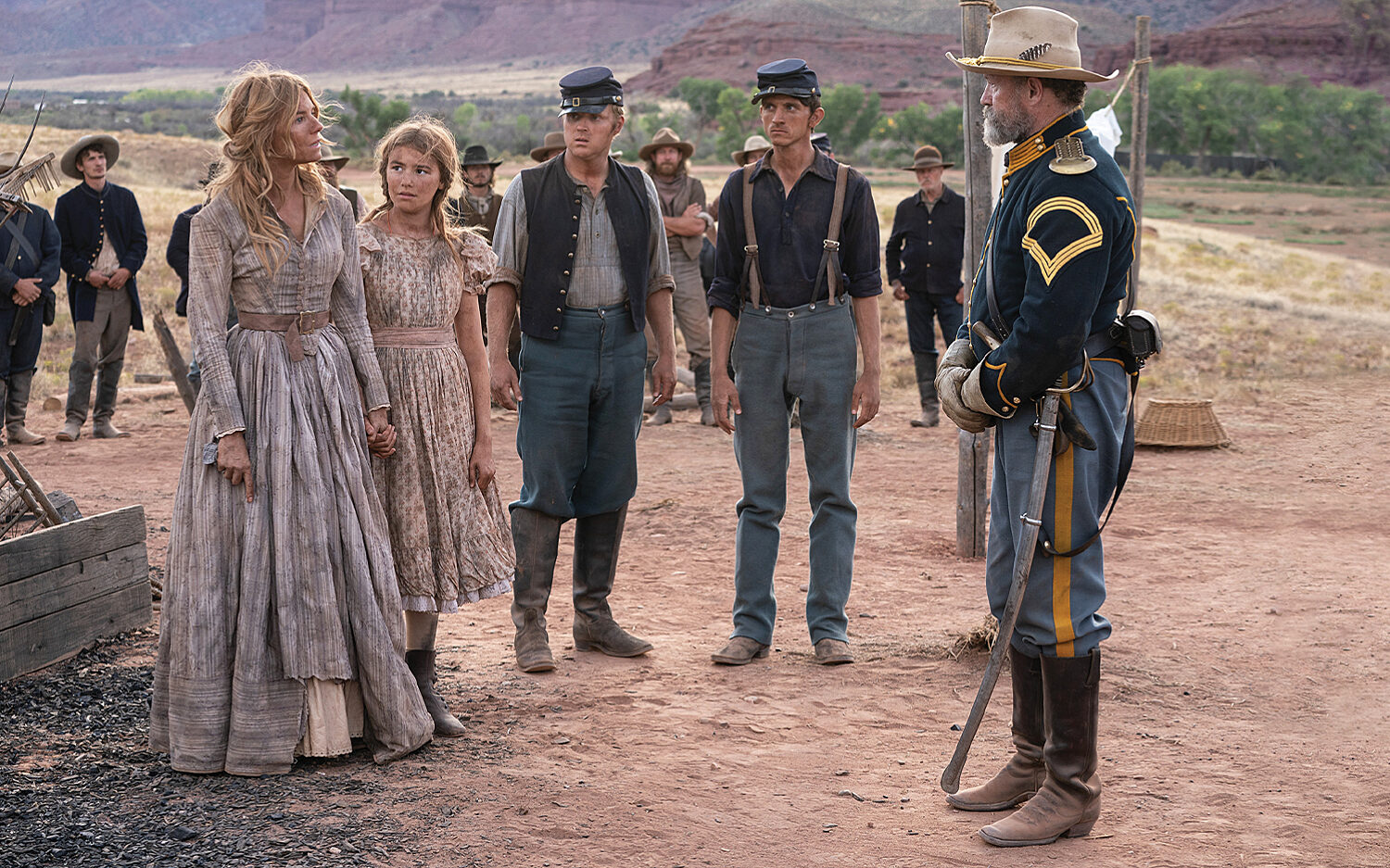

The Horizon story begins in 1859 in the San Pedro valley in Arizona, and the opening scenes show a surveying party measuring out plots in a vacant landscape. The plan is that these plots will develop into a new frontier town named Horizon. The brain behind this scheme is a ‘Mr Pickering’ (Giovanni Ribisi), whom we only see briefly at the end of Chapter 1. Throughout the film, there are references to the advertising handbill for the scheme, as various parties read it and are captivated by the idea of having a fresh start at a totally new location in the West. As a narrative device, it reflects the historical reality of land development during that period, but the key problem for the new settlers is that, while the landscape may look empty, there is an existing native Apache population. Unsurprisingly, they react violently and this provides one of the main story-lines of the film, focusing on the widowed settler Frances Kittridge (Sienna Miller), who is trying to rebuild her life at the local army fort after an Apache raid.

The film includes various story-lines that converge on the town of Horizon, including that of Hayes Ellison (Costner), who has been drawn into a vengeance tale after going to the aid of a woman and child. It is classic Western stuff, as he finds himself enmeshed in a feud, almost by chance, and is pursued across country. Another is a group of settlers in a wagon train led by Matthew van Weyden (Luke Wilson) who are facing the difficulties posed by weather, terrain and Native tribes in order to get to Horizon. There are internal difficulties posed by malcontents and also a feckless English couple who should, quite frankly, have been left behind.

The final main story-line is that of the Native Americans, and we see their reaction to the gradual encroachment into their homeland. This element is handled in an informed and sensitive manner. The Native American actors Owen Crow Shoe, Tatanka Means and Wasé Chief play key roles within this narrative. There are also glimpses of other communities within this tale of Western expansion—African Americans, Irish, Germans and a group of Chinese labourers, a demographic that is quite often overlooked. In the scope of its vision and its stellar cast, Horizon is reminiscent of Henry Hathaway’s vast How the West was Won (1962).

The key Irish voice is provided by veteran actor Michael Rooker, playing Sergeant-Major Thomas Riordan, who is ably supported by Elizabeth Dennehy as Mrs Riordan. He is one of the few sympathetic characters in the film, and the Irish sergeant-major echoes one of the standard characters of John Ford’s classic Westerns, usually played by that career Irishman Victor McLaglen. Research into the US army of the period would suggest that Ford’s stereotypes were based on reality. It is estimated that as many as 180,000 Irish soldiers served in the Union army of the American Civil War, while between 20,000 and 40,000 served in the Confederate army. Many of these were recent immigrants and thousands would later serve on the frontier during the ‘Indian Wars’. For example, over 120 Irish soldiers were serving in the 7th US Cavalry in 1876, and many met their end alongside Custer at the Little Bighorn, most notably Captain Myles Keogh from County Carlow.

The attention to material culture and costume is faultless and this extends to the Native Americans, with considerable care being devoted to getting Apache dress and language right. There are some seeming anomalies. On a couple of occasions, the local fort commander (Danny Huston) and the kindly cavalry lieutenant (Sam Worthington) refer to the Apache as the ‘indigenous’, which sounds jarringly modern and progressive. Otherwise, this is a lovingly crafted film with some stunning photography. At several points one wonders just how cameras were placed in locations which appear quite inaccessible in order to get specific shots over the landscape.

Theatre receipts following the release of Chapter 1 were disappointing and the release of Chapter 2 has been delayed. At the time of writing, Kevin Costner has suggested that the project will eventually include four chapters, each three hours long. It seems likely that these will see a limited theatre release, followed by serialisation on TV. Various reasons have been put forward for the poor audience reception. Most certainly this is not a film that will make Americans feel good about their own history. There are numerous dark characters, including a group of scalp-hunters, who reflect the more detestable aspects of westward expansion. Throughout, it is made abundantly clear that this was a phase of history underlined by human suffering. The length of the film may also be a factor. Michael Rooker has been particularly vocal in criticising modern filmgoers for their addiction to short social media clips and their inability to embrace and enjoy an epic film. It is in marked contrast to the audience excitement that surrounded Dances with Wolves in 1990, which was released to capacity audiences and was without the benefit of any online media promotion. It seems likely that aficionados of epic films, and Westerns in particular, will buy into Horizon in whatever format it appears. Considering the rapidly diminishing human attention span, however, we could be witnessing the last cavalry charge of the historical epic, among so many other things.

David Murphy is the director of the MA in Military History and Strategic Studies at Maynooth University.