By Conor Robison

It seems like poetic justice that Ireland’s parting shot at Oliver Cromwell proved to be the blackest day of his storied military career—doubly so, considering that the blow came at the hands of a man known as ‘Black’ Hugh. Cromwell’s silence on the matter speaks volumes about the generalship of his opponent, as does the brooding of his son-in-law Henry Ireton, who wrote long after of that agonising day in May 1650 when Cromwell’s hitherto victorious army dashed themselves bloody against that ‘sore breach … Clonmel’ on the River Suir. Yet the architect of this reverse was unknown to his enemy, to the point that when the town surrendered Cromwell pointedly asked the mayor ‘what that [Hugh] Duff O’Neill was’. The mayor responded that ‘he was an over sea soldier; born in Spain’, and had just withdrawn his garrison from the town. In a rage, Cromwell vowed ‘by God above, he would follow that Hugh Duff O’Neill wherever he went’. It was a promise not to be kept, as Cromwell left Ireland soon after.

AN EXILE COMES HOME

Born an exile in Brussels in 1610, a great-nephew of Hugh O’Neill, Hugh Dubh rose to manhood in the service of imperial Spain and only set foot in Ireland in his 31st year. Described in heroic terms by a contemporary as ‘one of the Prime Captains’, he followed his uncle, Owen Roe O’Neill, ‘out of that Vulcanian forge and martiall theater [of] Flanders’ to lend his sword to the cause of his ancestral land. It was desperately needed. By 1642 Ireland was in flames. The rebellion of the previous year swiftly spread from Ulster, and now armies of Scots and English Royalists were bringing the war to the infant Catholic Confederation of Kilkenny.

Military professionals from the Continent were badly needed to bolster the Confederate cause. Owen Roe and his men quickly set themselves up in Ulster, but with little money and few supplies they could not mould their countrymen into an army capable of dramatic operational feats. That would take time. Hugh Dubh, however, was made a prisoner of war in the defeat of his uncle’s army at Clones in June 1643. For the next three years he remained imprisoned, freed only in the wake of Benburb, where Owen Roe, supplied with money and arms enough to raise a proper army, smashed the Scots on the heights above the Blackwater. From this high point Confederate fortunes fell. A potential peace with Ormond, King Charles’s representative in Ireland, was scuppered by the machinations of the papal nuncio, Giovanni Rinuccini, who would not stand for a peace that prevented the open practice of Catholicism, splitting the Confederate Supreme Council.

Losses the following year at Duggan’s Hill and Knocknanuss destroyed much of the Confederates’ military strength, while the defeat of King Charles I and his execution in January 1649 forced many erstwhile Confederates to seek an alliance with James Butler, the Marquis of Ormond, in the name of King Charles II. Ormond’s efforts to seize Dublin from its Parliamentarian garrison came to grief at Rathmines, just two weeks before Cromwell himself landed. Granted enormous operational flexibility by the dispersal of Ormond’s army, Cromwell wasted no time in driving his sword deep into the Irish alliance. Drogheda’s gory fall set the tone. Ormond, growing desperate for support, looked to Ulster and the army of Owen Roe, but Owen Roe’s premature death in November took his army out of the fight, as its leadership sought to name his successor. All Ormond got was an already detached force of some 2,000 men under the command of Hugh Dubh.

‘THE STOUTEST ENEMY’

As with Cromwell, Hugh Dubh was unknown to Ormond. His cousin, Daniel O’Neill, made haste to express the foreshadowing opinion that Ormond would not ‘imploy any that will be more serviceable to your Excellency … than Hugh O’Neile’. Reassured, Ormond thrust Hugh Dubh and 1,200 Ulstermen into Clonmel that December. An old hand at sieges, Hugh Dubh kept his men busy strengthening its defences, a necessity lest they start harassing the locals. Hailing from the north of Ireland, these were the men whom Rinuccini insisted had grown ‘accustomed to suffering and [were] … more careful of their swords and muskets than their own bodies’. Fashioned into a disciplined fighting force by Owen Roe and his captains, they presented to Ormond’s eyes ‘a very considerable body of good foote’, who remained ‘cheerfull in the service’ despite the death of their beloved commander. Such cheer was necessary, for gloom had descended upon the Catholic/Royalist cause at the end of 1649. Ormond, chronically unable to keep an army in the field, was forced to disperse his troops in garrisons where they waited passively to be attacked by Cromwell one by one. This dispersal of strength behind high walls had thus far failed to halt Cromwell’s army, though disease killed his men by the hundreds. With the renewal of operations in January 1650, Cromwell confidently persisted in the same old formula of battering towns into submission.

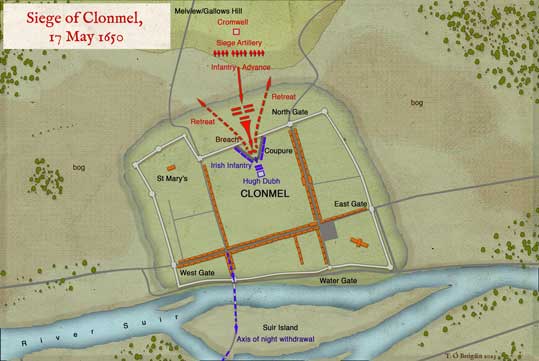

In March Cromwell pummelled Kilkenny and thence turned his eyes upon Clonmel. Backed by the River Suir, the town was encased behind 300-year-old walls 30ft high, with four gates flanked by turrets that opened into a town of narrow streets. It was not the most imposing town in Ireland but in Hugh Dubh it had a master of defence. A fifteen-year veteran of Spain’s war with the Dutch, a conflict of attrition characterised by sieges of such complexity as to make Cromwell’s affairs in Ireland look amateurish, Hugh Dubh would prove more than a match for Cromwell’s blunt approach to siege warfare.

DEFENSIVE PREPARATIONS

From the moment the New Model Army came before the town, Hugh Dubh strove to disrupt Cromwell’s preparations to place his guns in firing position, leading his men ‘on many valient sallies … to the enemies mightie prejudice’. Three weeks of ‘difficulty and daily hazard’ before Cromwell’s batteries were ready to pound the walls enabled Hugh Dubh to reinforce his position from within. That ‘surly old Spanish soldier’ quickly determined where the blow would fall and, using every available man and woman to hand, threw up a second line of defences fronting the anticipated breach, which consisted of ‘double works and traverse … strongly flanked from the houses within’. According to contemporaries, the breach was made serviceable by three o’clock in the afternoon of 16 May, yet the attack was delayed until 8 o’clock the next morning.

The delay only gave Hugh Dubh more time to sight guns on the gaping hole to his front. When the attack finally came, Cromwell’s assault force was met by a blizzard of shot ripping through their ranks. Lives were shattered amidst the iron torrent unleashed upon them, while spirited counter-attacks drove the weary New Model troops back with terrible losses. A stunned Cromwell could not persuade his men to maintain their foothold near the walls, the attack dissolving after hours of horrifying slaughter. Its renewal the next day was uncertain, for Cromwell ‘himself doubted of getting on the soldiers … to a fresh assault’. He needn’t have worried. Though Hugh Dubh’s defenders killed or wounded over 2,000 men, most of their ammunition was spent. Had Cromwell come at them again it might have been a different story. Ormond was nowhere to be seen, while a small relief force marching up from Kerry had been intercepted and destroyed weeks earlier.

With no reinforcements in sight, getting his regiments out alive to fight another day was the practical decision, one which Hugh Dubh hastened to execute while Clonmel’s mayor concluded terms of surrender. Three weeks at Clonmel cost Cromwell dear, but victory followed elsewhere, shattering Ormond’s alliance with startling rapidity over the coming months. While Hugh Dubh made for the line of the Shannon at Limerick, his uncle’s old army was annihilated not a month later on a Donegal hillside, ceding control of Ulster to the Parliamentarians in the ruinous battle of Scarrifhollis. Losses in Leinster and Munster followed until only the gates of Connaught remained closed by the famed fortresses of the Shannon. The following summer Ireton threw the bulk of his army against the chief of these, Limerick, and after four weary months Hugh Dubh’s plague-infested and starving garrison succumbed to an internal rebellion. Obliged to surrender when his own cannons were mutinously turned inward upon him, Hugh Dubh ended his struggle in November 1651, content in the knowledge of his ‘having only discharged the duty of a soldier’.

RETURN AND DEATH IN SPAIN

In defeat his life now hung by a thread as Ireton’s wrath rekindled. Cromwell’s son-in-law was a man upon whom ‘the blood formerly shed at Clonmel had made … an impression’. His desire to end Hugh Dubh for good was thwarted, however, by his fellow officers, who spared the life of an opponent known to have fought honourably and better than most. Operating with few men and scant resources in a country blighted by ten years of conflict, this battle-scarred professional was hailed by his enemies as ‘the stoutest enemy that ever was found by the army in Ireland’.

Having lost in the end, Hugh Dubh would ultimately return to Spain to die an exile’s death. And in exile he remained a shadowy figure, the foil of Cromwell, and one whose likeness no artist has cared to commit to canvas. While his stand against the greatest of Ireland’s bogeymen did not alter the outcome of the Cromwellian conquest, he must stand shoulder to shoulder with the likes of his uncle, Owen Roe, and great-uncle, Hugh, as one of Ireland’s greatest military men.

Conor Robison is a historian and writer from Chicago, Illinois.

Further reading

P. Gentles, The New Model Army in England, Ireland and Scotland, 1645–1653 (Oxford, 1992).

P. Lenihan, Confederate Catholics at war 1641–49 (Cork, 2001).

M. McNally, Ireland 1649–52 (Oxford, 2009).

M. Ó Siochrú, God’s executioner: Oliver Cromwell and the conquest of Ireland (London, 2008).