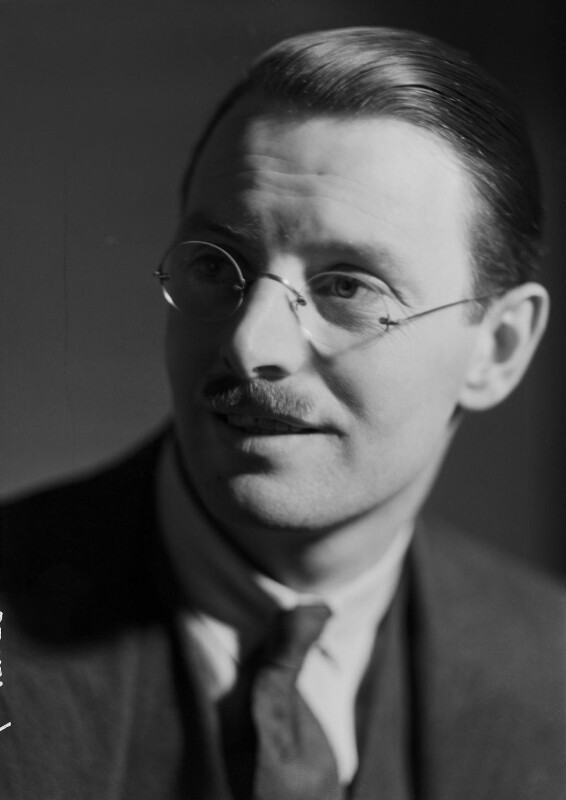

By John Grant

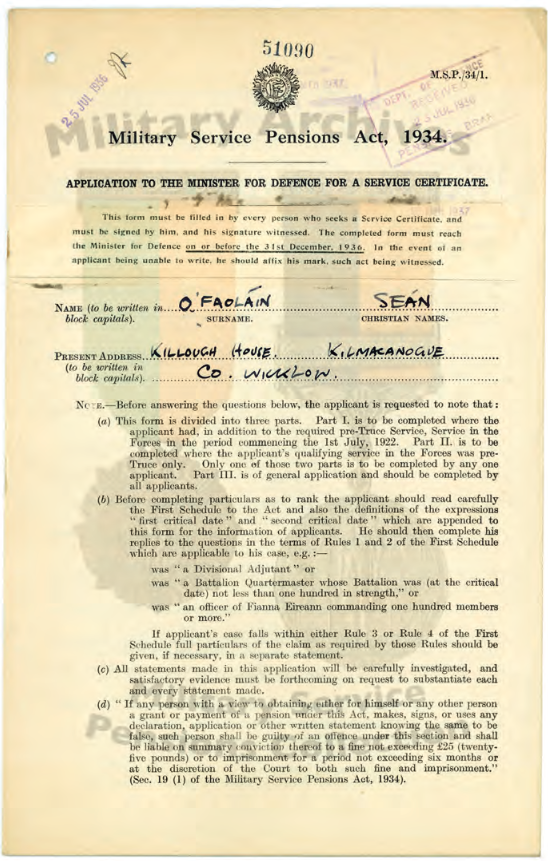

When Seán O’Faolain’s application for a service certificate landed on a clerk’s desk, signed and dated 22 July 1936, the document offered a private unveiling. His request to apply ‘for a pension as a member of the Irish Republican Army from 1918 to 1924’ was not administered for a year and, writing to ask the reason for the delay, the Cork writer reminded the panel of his dutiful patience and that his application required attention.

O’Faolain’s deposition is frank and contains an honesty that would be expected from a man who was to go on to publish and contribute to the social realist literary magazine The Bell. O’Faolain described himself as a ‘simple volunteer’, ‘a Volunteer under orders’, but there is a sense of detachment from what would be the essential and prominent attributes required of an IRA gunman—the sworn statement does not possess the necessary detailed collective actions naming fellow Volunteers who were ‘out’ on armed patrols, readied and eager for combat. In his sworn statement given on 23 November 1939, his testimony related the shooting of a man in a music shop, an event in which he took no part. When asked ‘Were you ever on armed patrol besides that?’, O’Faolain’s response conveyed a heartfelt honesty—‘I cannot remember that I was. That was not my kind of work particularly.’ Here lay the reasons behind the eventual outcome of his application.

DIRECTOR OF PUBLICITY, 1ST SOUTHERN DIVISION

At each particular period of his service, O’Faolain freely admits that ‘engagements’ with the enemy were non-existent and that he was armed with a revolver that ‘he did not shoot’. Other comments in response to questions concerning his military activities include ‘None worth the name’ and ‘None’, repeated throughout the application. In his statements, O’Faolain described the minor engagements discussed in his memoir as ‘None worth the name’, despite firing at a National Army truck in Cork ‘after a long muscular and moral struggle either with my nervous system or the nervous system of a stuck revolver’. He admitted that the real impact of the three rounds discharged at the truck was on his fragile nerves. According to this sworn statement, he held a gun for ‘two hours’. On paper, O’Faolain did occupy a fairly prominent role in the anti-Treaty struggle as director of publicity, 1st Southern Division—a position that he took over from Erskine Childers. As he stated in his deposition, he was on the run producing the army periodical An t-Óglach, which deserved genuine recognition and certainly did not release and absolve him from the danger of prosecution.

The application contains no direct references to incidents presented in his memoir and previously put into words in ‘Fugue’, a story that he wrote soon after his Civil War experiences in the collection Midsummer night madness (1932). In both his memoir Vive moi! (1993) and the eventual short-story portrayal, O’Faolain was ready for action—ready to ‘shoot home’ his rifle bolt and asking ‘When are we going to fire?’ He was, in these works, prepared to fire and test his nerves to the point of folly, and to ensure that this would be an engagement ‘worth the name’. Commensurate with the instances in his story ‘Fugue’, his character faced danger, possible capture and execution, and O’Faolain felt these dark and dangerous thoughts while ‘on the run’, as expressed within his memoir. This combat experience did not make it into the 1939 application.

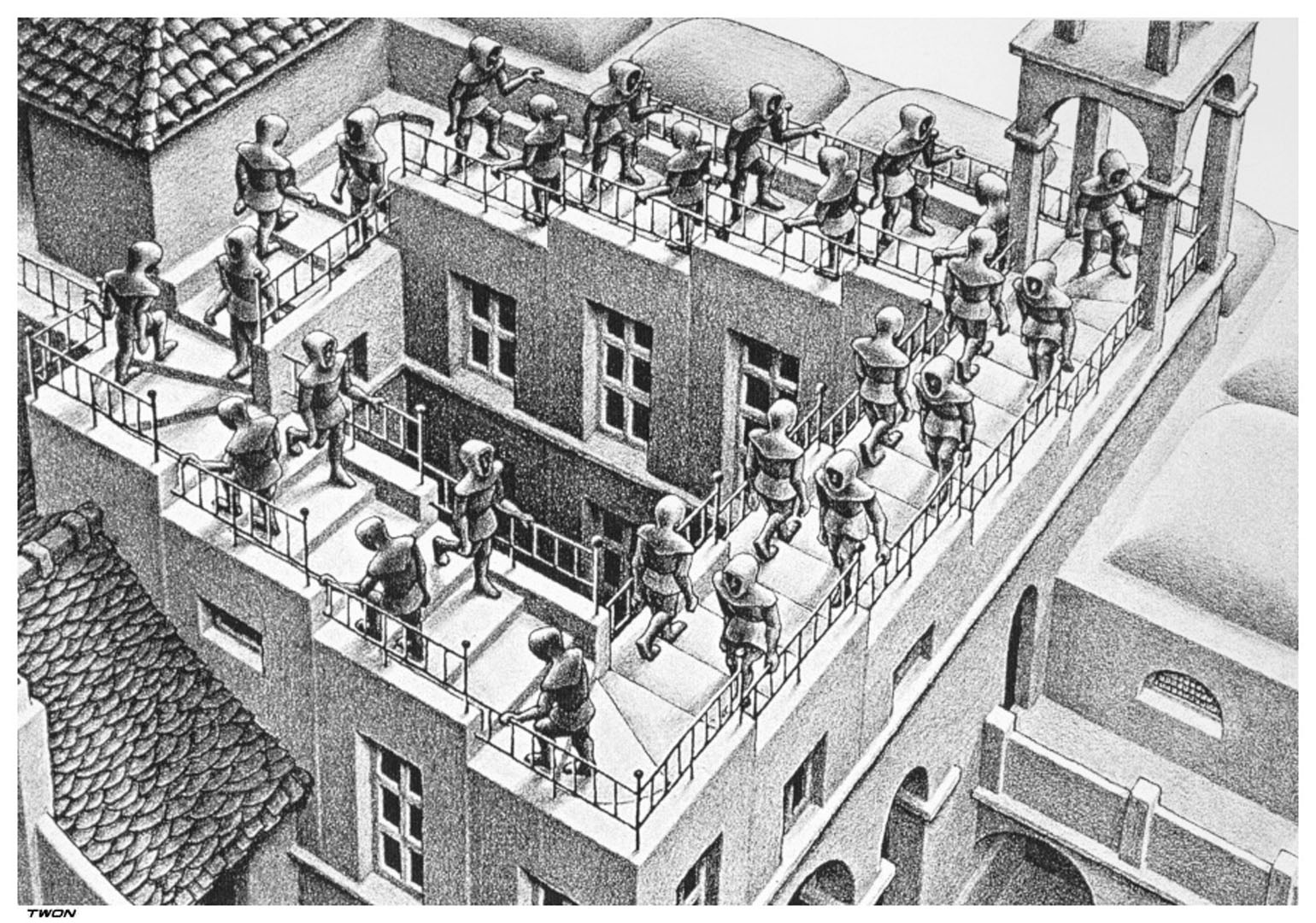

O’Faolain frankly admitted to confusion around the passage of time since past events. The recollections concerning his contributions to the republican cause, claims that would be tested and questioned before the board, are laid bare on the application form, but not all of them. Indeed, additional comments are made, and rectified omissions and directed arrows speak of something else. O’Faolain possessed a confused mind when it came to the Civil War—the application is a distorted recollection and mimics a Jackson Pollock ‘action’ canvas of steady confusion, or an Escher print of infinitely descending and ascending figures.

SACRIFICES

In O’Faolain’s opinion, he gave all the talents he had to offer for the Republic, resigning from his job owing to his allegiance and then failing to get it back. His personal difficulties were substantial, as his financial insecurity was all too real, and the application gave him the opportunity to tell of this sacrifice, as he gave up a ‘profitable job’ for the republican cause. As the Civil War drew to its stuttering conclusion, his former employers, Talbot Press, refused to reinstate him and consequently he was unemployed for two years. Understandably, he felt that some financial recompense was due to this ‘patient’ applicant, and an acknowledgement that ‘ever since I was 18 I have used my abilities, as publicist and propagandist, in every possible way, while a member of the Irish Republican Army’. He went on to state within the application, ‘Actually, I continued as Acting Director of Publicity, GHQ Dublin until 1924’. O’Faolain also claimed that he was proud of the letter of commendation received from the ‘acting president of the republic [in Dev’s absence]’, Patrick Ruttledge—so proud of it that he lost the cherished document! Nevertheless, when later minister for justice, Ruttledge attested to O’Faolain’s ‘excellent work in keeping the Republican position and the plight of the prisoners before the public both here and abroad’. Certainly, Ruttledge acknowledged the positive contribution that would eventually be dismissed by the pensions board.

O’Faolain’s ‘rough outline’ supplied to the board does possess the clarity and attention to detail that one would expect from this gifted writer. In addition, it is palpable that he was indeed genuinely proud of his contributions as a publicity agent for the IRA. In this initial document, there is honesty to the point of a humbling refusal to recognise the danger faced while ‘on the run’. O’Faolain, according to his ‘rough outline’, was arrested in 1919 but he freely admitted that he was detained for one night only. The reason is unclear; the arrest is not explored or pursued within his testimony and there are no clues within his memoir. Nonetheless, there is the correct affirmation that he manufactured munitions during the Civil War, and this was verified within references supplied. Manufacturing ammunition formed the basis of his short story ‘The Bombshop’ (1932). O’Faolain’s Civil War experiences were called on as material for his short stories and were frequently transposed from the Civil War to a less-complicated War of Independence setting. Dates and instances within the deposition tie in with his memoir; in response to the question ‘When the civil war broke out you were making munitions in Union Key?’, O’Faolain confirmed this and the essential germ of his story manifested through these experiences, with his knowledge of the streets of Cork providing the essential backdrop.

On 20 May 1937, a year after his original pension application, he wrote that his ‘silent patience now deserves your attention in the matter’. The trust placed in O’Faolain to take over from Erskine Childers warranted some form of acknowledgement by the board, he thought, given that he was promoted for all his effort. Although he conceded in a written note that ‘conditions’ were ‘rather confused in Cork in July [1922]’, he claimed that thereafter his position ‘became confirmed, definitely after the evacuation of Cork’.

His memoir revealed the actions that are unexpressed within his application: ‘firing downhill at a line of green uniformed figures advancing towards the village of Ballymakerra’. He certainly handled weapons and munitions for more than ‘two hours’. As his memoir makes clear, if found with arms, O’Faolain reflected, he would ‘end up that night against a barracks wall’. In his memoir, too, there is a ring of authenticity to the reflection that ‘the whine of bullets over one’s head, whether at two hundred yards or twenty, is an unpleasant sound’. Moreover, his referee, Michael O’Donovan, chairman of the Hospitals Commission, emphasised O’Faolain’s commitment to the ‘Republican position’ and the plight of incarcerated republican prisoners.

ORAL HEARING

Nevertheless, O’Faolain wished to be heard and, having requested an ‘oral hearing’, he was duly summoned to give evidence on 23 November 1939. His pension hearing and request were humiliating, but was the writer being wholly honest? He does freely admit to the dazzlement that can bring to the mind the ‘disillusion’ that comes with a lack of understanding, and perhaps the fog of memory had not lifted from those Civil War years. ‘Some images’ that washed over him in writing his biography in later years did not return in 1939 with the application on his desk and ready to be completed; the incidents within his biography are not cultivated within his application and perhaps it was too soon to confront the trauma of his revolutionary activity in the form of carefully formulated responses to standard printed questions.

In the end, ‘49115’, the reference number assigned to O’Faolain, a small slip of paper attached, contained the board’s response to the deposition: ‘Heard in Nov. 1939. No engagement. Not discussed with Officers. Reject.’ It was signed on 22 November 1940. The verdict went on to complain that ‘this is about the worst case I have seen. There is not any element of military service.’ For the board it was not enough. ‘You did the job you were best suited for’, they concluded, asking ‘Is there anything else?’ The impatience is palpable. It was an impatience underpinned by an assumption that the committee was there to support the fighting men and not those who valued a working typewriter as a weapon of choice.

Further reading

J. Grant, ‘“I was too chickenhearted to publish it”: Sean O’Faolain, displacement and history re-written’, Estudios Irlandeses 12, 50–9.

M. Harmon, Sean O’Faolain: a life (London, 1994).

S. O’Faolain, Midsummer night madness (London, 1932).

S. O’Faolain, Vive moi! (London, 1993).