Yet it is through participation on these occasions that diverse classes of Protestants have come to express and interpret their political position in a locality, their understanding of specific political issues, and their group identity. At various times the Twelfth of July has been used both by and against the state, by those demanding parliamentary reform and those hostile to it, by those demanding tenant-right and those opposing it, by working class radicals and even home rulers. Too often when the Twelfth is discussed, assumptions are made on the basis of a simplistic understanding of the nature of ritual occasions. We have to question the historical context of specific events while taking into account the way in which rituals work, firstly to give the appearance of political unity when in fact they encompass a plurality of political positions, and secondly to sustain the appearance of continuity, of ‘tradition’, in the face of great changes. The rhetoric of tradition has served to mystify the complex and sometimes contradictory politics of the Twelfth of July.

The press

The most substantial resource available for reconstructing the complexities of public rituals are newspapers. The press plays an important part in informing different understandings of the Twelfth and, in this sense, are part of the event. Reporting of Williamite commemorations was patchy up until the second half of the nineteenth century and, as always, was influenced by the newsworthiness of the event and the particular political position of the newspaper. After the late 1860s coverage is substantial with numerous descriptions of parades and verbatim reporting of speeches from all the major venues in Ireland. The Belfast Newsletter closely followed the political line taken by the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland and particularly prior to the 1870s was quite hostile to the procession and supportive of more passive Williamite commemorations such as annual dinners. The Northern Whig, whilst often critical of the celebrations, was not beyond supporting the ‘right to march’ when it politically suited, and also occasionally contested the meaning of the commemoration by suggesting a more liberal interpretation.

Throughout the twentieth century, northern newspapers, particularly the Belfast Telegraph and the Belfast Newsletter, have given wide coverage to the Twelfth. Often it is in the form of special pull-out supplements and picture montages of the holiday occasion, headed by phrases such as ‘IMPRESSIVE PAGEANTRY’, ‘THE LONG TREK BEGINS’ or ‘A SHOW OF STYLE AND DIGNITY’. In recent years, radio and particularly television, have replicated this style by broadcasting edited highlights, emphasising the ‘traditional’, religious image, and the holiday or carnival atmosphere of the day. This is in contrast to images portrayed by Irish nationalist and London-based newspapers, television news, documentary and drama programmes, which tend to stress the triumphalist, sectarian, political, and territorial images. This contrast has became more vivid during the 1970s and 1980s when the nature of some of the bands, hired by lodges, changed. Particularly in the Belfast procession, there was an increased number of the flute and drum bands (sometimes known as ‘blood and thunder’ or ‘kick the pope’ bands) with few members of the Orange Order in their ranks. Their behaviour might be described as a little less dignified than the majority of Orangemen and significantly they sometimes display symbols suggesting allegiance to loyalist paramilitary groups on uniforms, on instruments, and on flags. Such images are consequently ignored by some parts of the media and stressed by others. The historian is forced to consider the media, not simply as a resource, but as an active agent in constructing and reconstructing the meanings of the parades.

Beyond the wealth of material provided by newspapers there is a weight of documents, some public and others not, that can inform research. The House of Commons Committee of Enquiry into Orangeism of 1835, in which members of the institution gave evidence specifically discussing the control of party processions, is the most detailed of a number of government reports alluding to Williamite rituals. Most of the others concern civil disturbances in nineteenth-century Belfast. Quite clearly an analysis of the relationship between the Orange Institution and the state, such as that carried out by Senior for the period prior to 1835, is also possible with the aid of resources in various Public Records Offices. Moreover, there are a wide variety of Orange publications and commemorative Twelfth programmes, covering the last thirty years, in the Political Collection at the Linen Hall Library. Less accessible, however, are the minutes of lodge meetings, although some pertaining to the Grand Lodge of Ireland are open to review at the library of the House of Orange in Belfast amongst a variety of other materials.

‘Traditional’

Historians have not altogether ignored the important political role played by rituals, such as the Twelfth, but all too often there has been an assumption that a particular event’s meaning and function are unchanging. This is the supposition made when an event is described as ‘traditional’. On the other hand social anthropologists have made the understanding of ritual central to their analysis of politics. Nevertheless, much anthropological work tends to ignore historical material and therefore has also assumed the unchanging role and meaning of such occasions. However, recent publications by historians and anthropologists analysing the ‘invention of tradition’ (beginning with Hobsbawm and Ranger in 1983) have demanded that we take a closer look at the specific historical contexts within which such events occur.

For instance, Orange historian William Sibbert took the view that the early celebrations of William’s campaign in Ireland, such as that which inaugurated William’s statue in Dublin in 1701, can be seen as ‘the perfect model of Orange proceedings on anniversaries during past and present centuries’. He makes this assertion of a ritual taking place nearly a century before the formation of the Orange Order and the Act of Union, and before any clear political unity developed between Episcopalians and Presbyterians in Ireland. In fact the descriptions of the parades in Dublin, which were in part organised by the state from 1690 onwards (generally on 4 November, William’s birthday), bear little resemblance to the events of today. They would not have been motivated by the same aspirations and did not symbolise the same political group as more recent events. It is therefore misleading to assume a continuity of meaning between what might be found in Belfast in the twentieth century and what took pace in Dublin in the eighteenth.

The importance of analysing the particular historical context of a ritual is evident if we consider the use of Williamite anniversaries by the Volunteers during the 1770s and 1780s. In demanding reforms and greater powers for a parliament in Dublin they utilised the commemorative days in July and November, giving the ritual a new political focus to that already determined by the Dublin establishment. Indeed ‘The Boyne’ and ‘the American Revolution’ were commonly toasted together at Volunteer dining occasions marking WiIliamite battles. Such an appropriation of ritual was exactly what the Orange Order proceeded to do after its formation in 1795 albeit with a more reactionary political programme. Subsequently, there are occasions in the nineteenth century when the liberal press and O’Connell attempted forlornly to re-appropriate the Boyne as a ‘liberal’, or even panIrish symbol.

The term Orange man , we have always considered a misnomer. His loyalty is conditional, not permanent. … We remember the days when Orangeism was understood: when the independent Volunteers of Ards wore blue coats and Orange facings, and Orange hair in their caps. They were genuine loyalists.

Northern Whig, 8 July 1824.

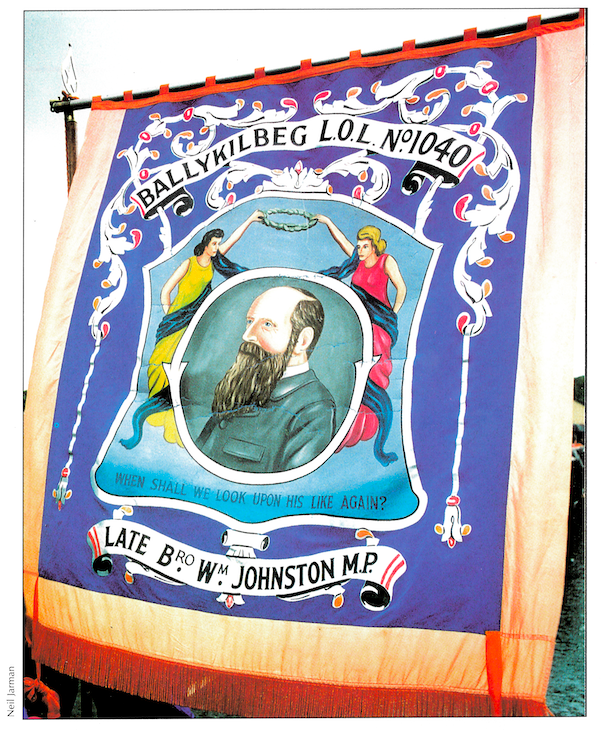

William Johnston of Ballykilbeg

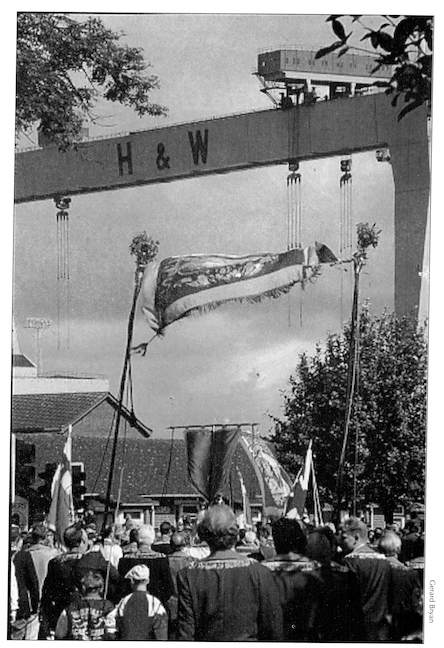

When William Johnston of Ballykilbeg was elected MP for South Belfast in 1868 he had effectively used the annual celebrations of the Battle of the Boyne, on 12 July, to defeat the Tory candidate put forward by the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland. For much of the previous five decades, the gentry of the Orange Order had chosen to acquiesce to laws controlling the right of party procession (1832-1844, 1850-1872) and to the desire for civil order. Many had abandoned the ritual processions of the Twelfth and instead resorted to writing righteous letters, often addressed from London, pleading with ‘their’ brethren, in the name of loyalty and the rule of law, not to parade in public on the First or Twelfth of July. In doing so they were asking rank and file Orangemen to relinquish the event which most expressed their identity, loyalty and limited political power. Working class Orangemen were less willing to abandon the ritual and consistently paraded on the Twelfth throughout the nineteenth century despite their Grand Lodge and the law. However, unlike others in the Grand Lodge, Brother William Johnston was prepared to go to jail in support of the right to march. After a ‘monster procession’ in 1867 he was imprisoned and on his release he ran his successful election campaign.

While William Johnston may well have been motivated by his principles as an Orangeman, as a politician, he mobilised a diverse political body using Twelfth processions. He combined his staunch Orangeism with the suggestion that the Belfast working classes had been abandoned by the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland. At least for a short time he had appropriated from the Tory gentry the right to dictate the meaning of the event. He was loyal and they were not. The reported speeches made at the field were replete with superlatives about Brother Johnston and few others. At a ‘great demonstration’ in Waringstown, on 13 July 1868, William McCormick, Deputy Grand Master of Belfast, proclaimed William Johnston as ‘the leader of thousands of Orangemen in Belfast and one hundred thousand in Ulster’ and that Protestant working-men should demand justice from the factory and land owners of the province. Johnston had used the Twelfth procession and the platform at the field to build political popularity and turn it into votes.

The Independent Orange Order

The use of the symbols and rituals of Orangeism by competing class interests is also illustrated by the schism in Unionism from 1900 to 1906 and in particular in the formation of the Independent Orange Order (100) who from 1903 held their own Twelfth processions. One of its founders, T.H. Sloan, used a staunch version of Orangeism in much the same vein as William Johnston, combining it in a more explicit way with working class radicalism in opposition to the Tory-dominated Grand Lodge of Ireland. The new Order published Orangeism: its history and progress – a plea for first principles (1904) as an attack on the Grand Lodge.

If Ritualism be rampant in Ireland today, it is due to those who hold high office in the Orange Order. If the Protestant farmer has been forced to emigrate and hand over his homestead to a Roman Catholic, it is largely the work of the Orange and Tory landlords, who in the past endeavoured to placate the farmer by inoperative Orange resolutions; and who, to-day, stand athwart the path of national progress, barring the way to the complete realisation of the Land Acts and Reform Acts by the Orange democracy of Ulster. If the British have betrayed the Irish Protestant minority, and regarded the Orange institution as the pocket borough of Toryism, it is due to the Orange leaders whose address is Carlton Club!

The history of Orangeism since its modern establishment in 1795, reveals a continual struggle by the rank and file for the practical application of the principles of Orangeism to the problems which every day come up for consideration and solution. In an incident preceding the split in the Orange movement, at a Twelfth parade in Castlereagh in 1902, Sloan actually mounted the platform and confronted Colonel Saunderson MP,leader of the Irish Unionist Party and Belfast County Grand Master. He charged that Saunderson had voted against a clause legislating for the inspection of convent laundries as part of the Laundry Bill. Whilst the odd heckler was not unheard of at the formalities of the platform speeches, such an affront was highly unusual and Sloan was later condemned by the County Grand Lodge. The Independent Orange Order could subsequently cast Sloan in the direct lineage of William Johnston, particularly as Sloan won the South Belfast seat of the recently deceased Johnston by defeating the Belfast and Conservative Association candidate backed by the Orange Institution. At an 100 demonstration in Maghermorne on 13 July 1905 brethren were introduced to one of the most remarkable documents in Irish history, The Maghermorne Manifesto. Written by Robert Lindsay Crawford, the Imperial Grand Master of the 100, it attacked false conceptions of nationality amongst the rulers and people of Ireland, called for compulsory land purchase for tenants, and accused governments of playing off Irish Protestants and Catholics against each other. With its clear attention to class politics, and its interpretation of Unionism in terms of a form of Home Rule, it took Orangeism to new political horizons. However, by 1906 when Sloan retained his seat, he was in the process of repudiating much of what the manifesto contained. On the other hand, by 1908 Crawford’s increasingly radical political position was such that he was suspended from the 100. Nevertheless, the 100 continues to exist in the 1990s, particularly in North Antrim and, if nothing else, retains its opposition to the direct partnership of Orangeism and the Ulster Unionist Party.

Ritual and politics

Given that ritual possesses such powerful possibilities, we must at least attempt an historical undered with the Williamite campaign, has played a significant role in the political processes of Ireland. Once we have stopped assuming that the rituals have always existed in their present form and performed the same political function, then we can start to ask real questions about the process of political identity. As the political situation changes so might the role of some of these events. For example, the broadening of the franchise, as happened just prior to the election of William Johnston, may well have increased the political importance of the platform speeches made at the field during a Twelfth parade. After all, the way the mass of the population experience politics is not through a splendid speech made by a politician in parliament but rather memorative and celebratory occasions as well as political rallies.

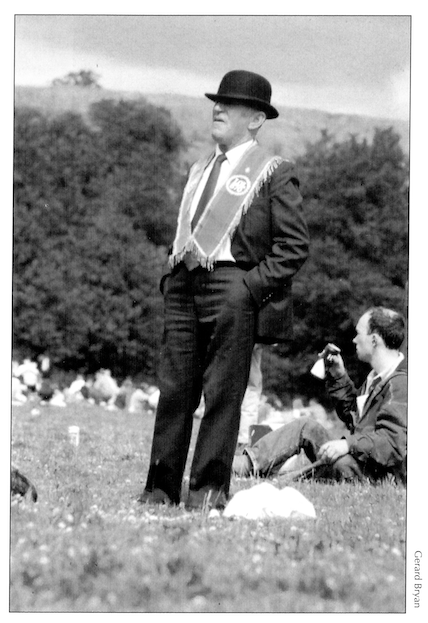

Reconstructing the politics surrounding a ritual is difficult. To those not involved in the event a particular meaning might appear obvious. Politicians and journalists frequently view all parades as simply sectarian expressions of Protestant ascendancy. However, anthropologists have shown that there is a wide range of understandings and motivations connected with the involvement of individuals in a ritual, and furthermore, that those motivations change. Indeed, that is part of the power of a ritual: it brings people together under one set of symbols without necessarily forcing upon them one set of meanings. Thus the same Orange parade could contain the politically radical worker, the deferential worker, the Conservative factory owner, the ritualistic Episcopalian, the good-living Presbyterian, as well as boys and girls simply looking for a good time. The event can at once be political, religious and carnivalesque. Unlike the politician at the head of the parade, the attitudes of the most of the participants are rarely recorded. Nevertheless, despite the different motivations involved, the ritual still manages to express to outsiders the comappearance of a political community

Dominic Bryan is a research officer at the Centre for Conflict Studies atUniversity of Ulster, Coleraine.

Further reading

J.W. Boyle, ‘The Belfast Protestant Association and the Independent Orange Order 1901-10’ in Irish Historical Studies (1962-3).

P. Gibbon, The origins of Ulster Unionism (Manchester 1975).

E. Hobsbawn & T. Ranger (eds.), The invention of tradition (Cambridge 1983).

H. Patterson, Class conflict and sectarianism (Belfast 1980).