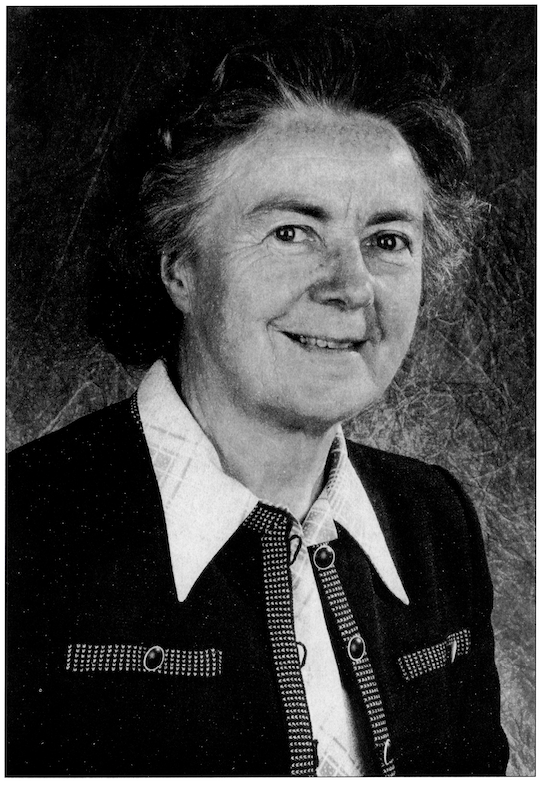

Interview with Margaret MacCurtain by Thomas O’Loughlin

TO’L: Why did you become a historian?

MMacC: I can see many cycles in the pattern of my life, and in my intellectual life in particular, that play into my becoming becoming a professional historian. The choice of history ran right though my school subjects, especially as I approached the Leaving Certificate. It was one of my subjects at university — at that time one could take more subjects in first and second arts than is the case now — and then at post-graduate level I used my MA thesis (on the Counter-Reformation) to enhance my teaching skills in the school in which I taught at senior-level as a Dominican Sister. Later at doctoral level, decisions taken both with my consent and around me by my supervisor in UCD, Professor Dudley-Edwards, and also by my superiors in the Dominican Order, shaped my evolution as a professional historian. We are talking about a period when life was still very structured in the pre-Vatican II mould; the amazing thing was that I was consulted about whether I wanted to be an historian.

TO’L: What qualities do you admire in historians?

MMacC: I enjoy the ability of the writer to give a satisfying coherent analysis of the historical investigation being carried out. I am not an avid detective story reader, but I admire that talent for picking up the clues from a body of evidence, organising and arranging the pattern. Then there are the qualities of ‘contextualising the document’. Finally (I suppose here is where I am eclectic)I admire work where the writer contributes a style that rises above the pedestrian. When I find those qualities together, whether it is the work of a professional historian, or a popular history writer, or in an undergraduate paper, I recognise it as excellent historical writing.

TO’L: What trends in the writing of history have influenced you?

MMacC: I am not an historian who consciously sought to be part of this or that movement or trend within history. But, looking back I realise that various trends in history writing have influenced me: for a long time in my youth I read and re-read, Marc Bloch’s The Historian’s Craft . J.C. Beckett’s collection of essays, Confrontations, came at an important stage in my insertion into writing Irish history. He made me realise that to look at Ireland’s past was to see a series of disjunctions which the historian had to confront. This meant confronting painful, complex and often difficult themes.

TO’L: Are there any heroes or heroines whom you admire?

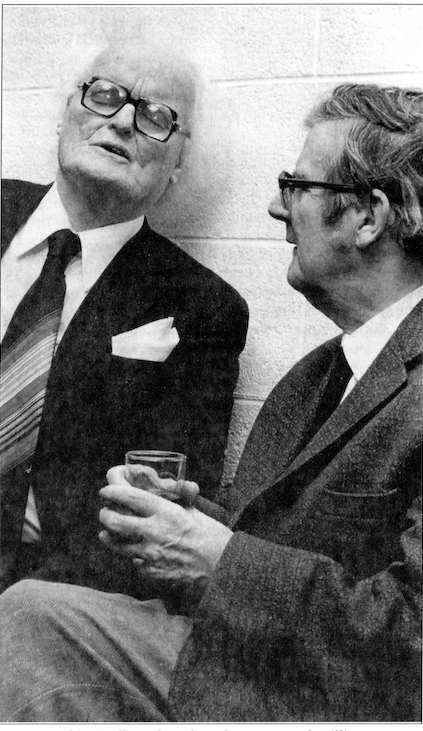

MMacC: I am not a person who admired heroes or heroines, but, I can see now looking back, there have been people who have influenced me. Obviously Jesus Christ is one, and his four biographical commentators who have been monitoring my life. Paul and Aquinas as two shapers of theology have influenced me, and also made me buck against the system. I have been influenced by both my parents. My father was scholarly, a school inspector. He loved Old Irish and he loved to read history — he had the Annals of the Four Masters at home. My mother was part of that first wave of feminists; she had been a banker and was a very liberated person. Of the academics who have influenced me, Dudley-Edwards and the circle in the Modern History department here at UCD have been a strong influence on me. Dudley-Edwards was a towering personality to all those who knew him in his hey-day. In contrast, T.D. Williams had a special enchantment for those whom he allowed into his conversations about history. I revered Maureen Wall, the historian of the eighteenth century, of the Penal Laws and of the Catholic Question, for her passionate investigation of one of those painful problems we have to face. It is a great delight to me to have a working friendship with Mary Daly and Mary Cullen of Maynooth. In a category all of her own, I would put Hilda Tweedy for her work, A Link in the Chain, which came out from Attic Press in 1991.

TO’L: For many years you have been associated with women’s history and women in history. Could you tell us about that?

MMacC: It is exhilarating for me that I complete the period of my life which has been connected with history teaching in UCD with a deep involvement with development of the writing and publishing of women’s history. There has long been an involvement by women in writing history: Eileen Power’s books influenced me as a student and Mary Hayden was one of the first women professors in UCD. But there were decades of history-teaching where women’s history played no part. Then in the 1970s women’s history arrived, partly as a search for roots on the part of the second-wave women’s movement who wanted to find out where they got lost and what had happened, and methodologically, because the tools of social history, particularly economic history, began to be widely used at that time and these were the best tools for researching women’s history. It has developed in many ways since. For instance, Catríona Clear takes into consideration not only new approaches to the writing of religious history but also asks crucial questions that apply to the social history of nineteenth-century Ireland such as why did Irish convents go for a structure with two tiers of ‘choir sisters’ and ‘lay-sisters’? It seems to me that the professional woman historian in this generation brings a variety of skills and methods that will enhance the profession, for instance a recognition that a text has to be seen in its context, has to be broken down to discover the evidence behind the evidence, and an awareness of the need for gender analysis. Women’s history brings another dimension: women generally cannot afford the luxury of living in their heads and so bring a realistic approach — scepticism — to the idealistic norm of historical objectivity.

TO’L: Ireland has been described as a society dominated by history. Would you care to comment?

MMacC: Societies hold their memory of the past as a continuum flowing into their present. Ours is a very long past and there is the long oral tradition of story-telling and recalling the past. The person who recalls the past has an important and special role in such a society, not just recording the past in terms of actions and events, but also of conveying the mythic level of that society. The historian is a part of that process and adds to it the detailed record of actual happenings, hence the value of a work like the Annals of the Four Masters or the Annals of Connaught.

TO’L: Would you accept a distinction between ‘annalists’ and ‘historians’?

MMacC: Certainly not. When it comes to a society as old as the society on this island, one that has had layers of settlement added to it every 300 or 400 years, you cannot make that kind of division for we are all part of that layered memory carrying the past into the present.

TO’L: You have also been associated with the writing of religious history. What developments have you seen in that area?

MMacC: With the setting up of the schools of Irish history associated with T.W. Moody, Dudley Edwards, and Hayes-McCoy, a new approach to looking at the past emerged. First, it was in a secular setting and that impacted on the writing of Church history. Second, there have been advances in the techniques of church history. For instance, in recent decades we have seen the application of a hermeneutic of suspicion of various questions concerning the role of religion in Irish society. This has set up a fruitful tension between the results of historical research and the ‘authorised tradition’ — for example, E.R. Norman’s portrait of Cullen.

TO’L: What state is the history profession in at the present time?

MMacC: As a group historians are an important professional body, both nationally and internationally — one which advises governments, upholds the norms of responsible journalism, and promotes true research in areas of interest to society as to what actually happened in a particular period. It is a growing profession. It makes an important contribution to publishing, and it makes a contribution to the running of that world of learning that is the contemporary university.

TO’L: Have you any fears for the profession?

MMacC: Some historians at present do have fears that history will become a backwater. I do not accept such a gloomy forecast. My main fear is that we in Ireland give our young people both at school and in university such a strong penchant for political history that they will forget the other dimensions of religious, cultural, settlement and local history — I am thinking of the sort of work being done by Kevin Whelan and William Nolan which can easily be ignored in the rush for political history. I also fear that a loss of memory may occur, not of our recent past, but of the roots that have nurtured our intellectual life in the west over centuries, for instance the decline in the numbers specialising in the difficult techniques of medieval history.

TO’L: What are your hopes for history?

MMacC: For at least thirty years, since I attended a seminar on bias in the teaching of history in the early 1960s, I have sought a history that can help reconcile societies. Since then there have been many developments along these lines; work by organisations like the Irish School of Ecumenics; the series of investigations, Reconciling Memories; and the research sponsored by the Institute of Irish Studies in Belfast. All this work gives me grounds for optimism and my hope is that this kind of work will flourish. History can only explain the past, it cannot change behaviour. But that larger dimension of history, when history seeks to reconcile and synthesise the past — rather than divide people into camps and set antitheses between ethnic groups and religious sects — is something very dear to my heart.

TO’L: If you look back on your writings, which piece has been the most significant, or which you would like to be remembered for?

MMacC: It would be a surprising choice, a small book — now out of print — from 1978 which I edited with Donncha Ó Corráin, Women in Irish Society. Its essays (there was one by Mary Robinson) are an expression of the vitality of the intellectual and creative energy of the 1970s.

TO’L: You have been a teacher who has encouraged many young historians. Have you any words of advice?

MMacC: Do your own research; be courageous and innovative; trust your own thinking; respect originality in yourself and in others.