By Fiona Fitzsimons

In the early years of Elizabeth I’s reign, Jacob Aconcio, an Italian inventor in England, sent a carefully worded petition to the queen:

‘Nothing is more honest than those who, by searching have found out things useful to the public, should have some fruit of their rights and labours, as meanwhile they abandon all other modes of gain, are at expense in experiments, and often sustain loss, as has happened to me. I have discovered most useful things, new kinds of wheel machines, and of furnaces for dyers and brewers, which when known will be used without my consent, except there be a penalty, and I, poor with expenses and labour, shall have no returns. Therefore, I beg a prohibition against using any machines … like mine, without my consent.’

In England, private franchises and monopoly grants were part of Elizabethan fiscal policy. What distinguishes Aconcio’s petition from others is that he sought letters patent for what we now recognise as intellectual property rights. Even that in itself was not new: the Venetian Republic granted patents for inventions before 1420.

In England, Ireland and Scotland letters patent continued to proliferate, as private individuals and groups looked to control innovation, manufacturing and trade. In 1624 the English parliament enacted the Statute of Monopolies to end the stranglehold over commercial activity. The act repealed many patents and monopolies and gave inventors rights over their own inventions for fourteen years. It transformed patents from a privilege given by royal prerogative to a property interest vested in the common law. In Ireland letters patent remained one of the privileges of patronage.

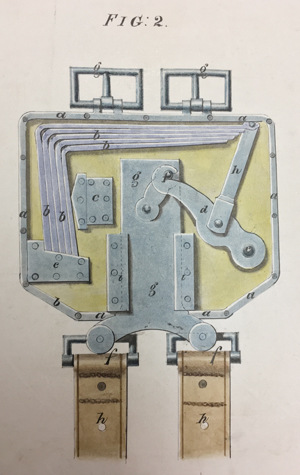

Patent records of inventions are a less usual source for family history, but they always come with a story attached. The details usually found in each patent include the name, address, rank, occupation or profession of the patentee; the title of the invention; the terms of the patent granted; and the date of the grant. From the 1730s patentees had to provide technical specifications of their inventions.

The British Library has a comprehensive collection of all English patents from 1617 to 1899. For the period between 1852 and 1899 the collection includes copies of all UK patents, including those of Ireland and Scotland. The UK National Archives in Kew hold the original enrolments of patents in separate series. Unfortunately, the original records relating to Irish patents do not survive.

The British Library patent collection survives in pamphlet form. The collection can be divided into two parts: the early English patents (1617–1852) and British patents (October 1852–1899). In the mid-nineteenth century the early English patents collection was created, using the original documents sent in by the inventors. All extant paperwork was reassembled and transcribed—from drawings to technical specifications—and the grant recorded in the Patent Rolls. Once done, every patent was placed in chronological order, assigned a number in order of sequence and published as a pamphlet. The usual caveats apply, as with any work retrospectively ‘created’.

From October 1852 British patents were printed and published weekly in pamphlet form. Patents were numbered in annual sequences, so you will need to search by patent number and year. All surviving pamphlets have been collected, arranged alphabetically and published in volumes. The patents from 1617–1852 are contained in one volume, whereas between 1853 and 1899 an annual volume of patents was published, clearly showing the huge growth in technological innovation in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Fiona Fitzsimons is a director of Eneclann, a Trinity campus company, and of findmypast Ireland.