By Micheál Ó Siochrú

‘I am struck by a disinclination in both academic and journalistic accounts to critique empire and imperialism. Openness to, and engagement in, a critique of nationalism has seemed greater. And while it has been vital to our purposes in Ireland to examine nationalism, doing the same for imperialism is equally important and has a significance far beyond British/Irish relations’

(President Michael D. Higgins, The Guardian, 11 February 2021).

Western colonial legacies continue to generate heated debate in the US, the UK and now in Ireland. President Michael D. Higgins highlighted significant weaknesses in the existing historiography relating to Ireland’s engagement with, and role in, the British empire. From the 1960s, a succession of scholars sought to dismantle what they termed ‘nationalist myths’ while simultaneously downplaying the impact and legacies of English/British colonialism. Some of the more recent work continues in this tradition by focusing on alleged Irish culpability in the British imperial project. By actively participating in imperial civil and military structures, the whole nation purportedly colluded in the crimes of empire. This premise, however, is highly problematic, as many of the more prominent ‘Irish’ identified in this manner—individuals such as Aungier, Cole and Briskett—actually belonged to the English and Scottish colonial settler communities in the first place, while the motives of those signing up for military service, or to work in the civil administration, varied widely from economic necessity to personal opportunity. The involvement of people from Ireland in various British colonial endeavours is undeniable, but this desperate need to associate with the oppressor, an academic form of Stockholm Syndrome, surely makes Ireland unique among former colonies. It is hard to imagine Indian historians, for example, lining up to blame their entire nation on account of the tens of thousands of sepoys serving in the British armed forces, or the millions of indentured labourers and merchants from the subcontinent who ‘colonised’ east Africa and the Caribbean under the aegis of British imperialism.

The complexities of Anglo-Irish relations continue to attract scholarly attention, but the fundamental nature of the power relationship remains perfectly clear. Military conquest and settler colonialism laid the foundations for the economic exploitation of Ireland, alongside sustained discrimination directed against the indigenous population, who continued to struggle both militarily and politically for different forms of autonomy. From the outset, the English justified their intervention in Ireland on the basis of alleged cultural superiority. Yet the seventeenth century witnessed a significant modification in English thinking on Ireland, based on new imperial priorities, forged in the furnace of the Cromwellian reconquest of the early 1650s and the land settlement that followed. Instead of preaching ‘civilisation’, policy-makers in London and Dublin increasingly gave precedence to commercialisation, trade routes and revenue, seeking as a result to transform the Irish economy and to maximise profits. No figure embodies these changes better than William Petty, Cromwellian surveyor, economic innovator and the father of political economy, according to Karl Marx at least. Mapping the entire country in extraordinary detail, while assigning a variety of agricultural commodities to columns on a ledger, Petty imagined depopulated lands in Ireland feeding an imperial market in an unsettling glimpse of social engineering in its early, confident, arrogant phase.

‘LABORATORY OF EMPIRE’?

Historians have long argued that it is impossible to fully understand the history of early modern Europe if the ‘domestic’ and the ‘imperial’ remain separate. This is especially true for seventeenth-century Ireland, which occupied an unusual position: a kingdom in constitutional terms but a colony in practice. As the seventeenth century progressed, the country combined elements of both the ‘old world’ of Europe and the ‘new world’ emerging across the Atlantic. From the 1930s, scholars such as D.B. Quinn sought to link Ireland’s story to the wider history of early modern European expansion, particularly the forced and voluntary migrations of people to the Americas, while more recently historians claim that Ireland acted as a kind of ‘laboratory of empire’. Accordingly, English rulers used Ireland from the early 1600s to test out methods of control and colonisation that they later applied overseas. Not everyone accepts this idea, cautioning that just because things happened at the same time does not necessarily imply a direct connection between them. Still, the ‘laboratory’ metaphor has proved resilient. Promoters of plantation schemes across the English empire often worked from the same set of assumptions, with merchants, investors, military officers, civil administrators and clergymen moving between colonies, spreading shared values and pursuing personal fortunes. These colonies also developed similar governmental structures, such as local assemblies and courts, but—with the exception of Ireland—direct state intervention remained relatively limited at first.

The mid-seventeenth century, however, witnessed significant upheaval on this side of the Atlantic, spreading throughout England, Scotland and Ireland. When it comes to Cromwellian Ireland, historians continue to focus on the brutal conquest. The genocidal campaign involved a series of notorious massacres, alongside the deliberate targeting of the civilian population and widespread destruction of the country’s infrastructure, resulting in a demographic collapse on a dramatic scale. Petty, obsessed as always with numbers, estimated the losses to be in the region of 40%. Oliver Cromwell now remarked that ‘Ireland was as a clean paper … capable of being governed by such laws as should be found most agreeable to justice’. In other words, he regarded England’s oldest colony as a blank slate upon which to impose his vision of order and reform. The subsequent land settlement, involving millions of acres of fertile agricultural land, witnessed the forcible replacement of thousands of Catholic landowners by a Protestant Ascendancy class, which dominated Ireland’s political and economic landscape until the great land reforms of the late nineteenth century.

GROWING DIGITAL ARCHIVE

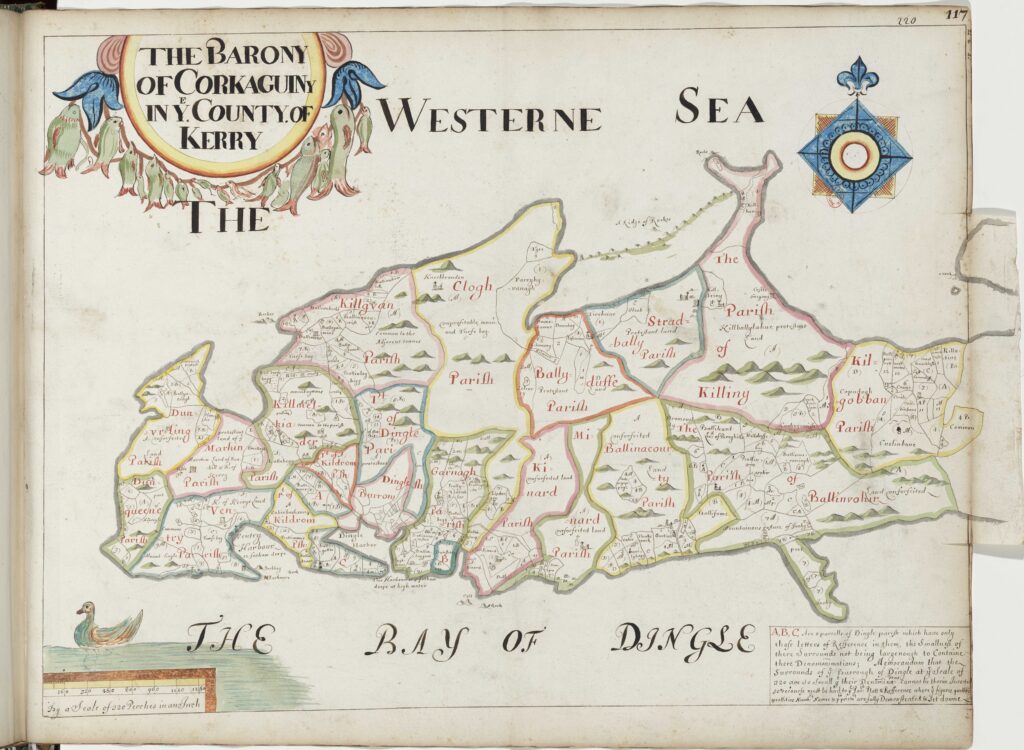

Historical studies of this traumatic and transformative period remain thin on the ground. There are several reasons for this, including the destruction of the Irish Public Records Office in Dublin at the outset of the Civil War in 1922, when 55 volumes of documents from the Commonwealth and Protectorate era went up in flames. These orders, warrants and financial accounts, alongside official government correspondence, comprised precisely the material required to assess the Cromwellian regime in Ireland. Moreover, few engaged seriously with the vast records on the land settlement produced by William Petty’s Down Survey and the subsequent Books of Survey and Distribution. That situation is set to change. Thanks to new technologies, this abundant material is becoming far more accessible and usable. The award-winning Down Survey of Ireland project, relaunched in 2025, has brought together all the surviving maps and data produced by Cromwellian surveyors under Petty’s direction, alongside the Books of Survey and Distribution, which will also be published shortly in five volumes by the Irish Manuscripts Commission. Now freely available online (https://www.downsurvey.ie), this growing digital archive, alongside other newly discovered material, is transforming the historiographical landscape, opening up fresh possibilities for engaging with Cromwellian Ireland in the process.

One central question must be addressed: how exactly did the English republican regime govern Ireland in the 1650s, both domestically and as part of a wider Atlantic world, and how did this shape the global British empire that emerged? Ireland must be studied in a broader, international context, as part of an Atlantic system through which revolutionary England pursued its colonial ambitions. Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland marked the real beginning of England’s state-backed overseas expansion. The conquest and the massive land transfers that followed signalled a turning-point, with England now becoming a centralised state capable of projecting power far beyond its borders, laying the foundations of empire. But while the broad outlines are understood, the details of how this transformation actually happened still need to be pieced together. For Stephen Saunders Webb, military rule lay at its core, when from the 1650s Cromwell extended ‘garrison government’ to Ireland, and the model later spread to England’s American colonies. He argues that military men, placed at the heart of colonial politics, helped create an empire built on territorial expansion, plantation, political coercion and centralisation.

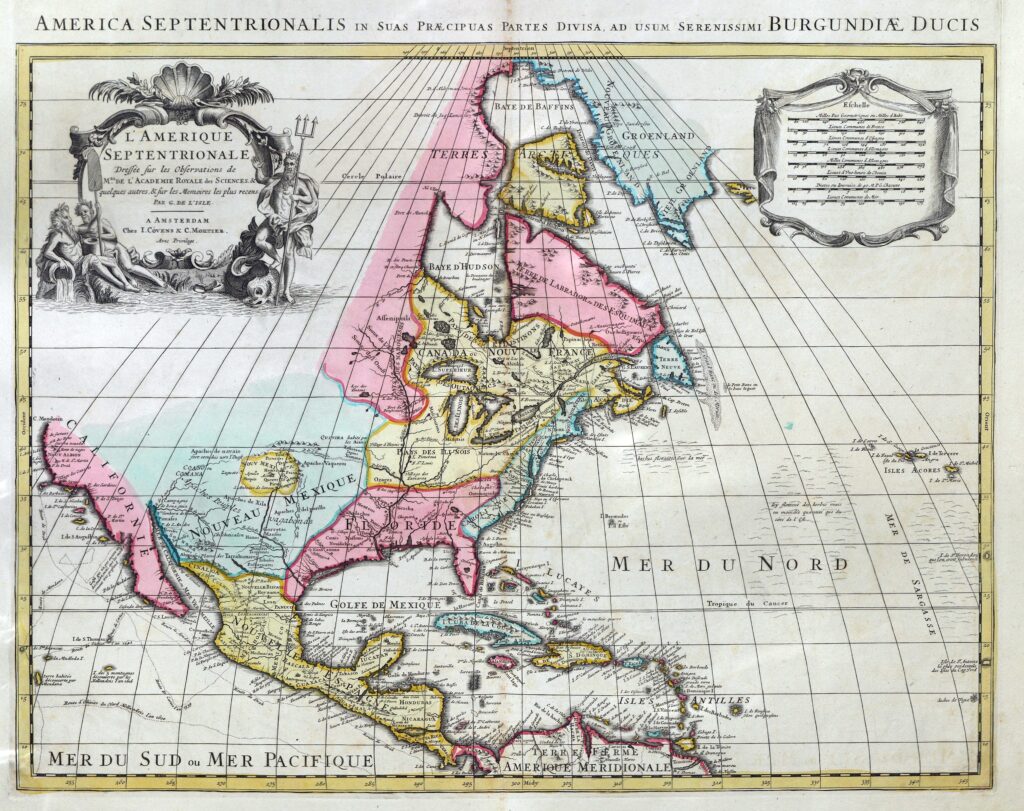

The English military unquestionably played a central role, but only as part of a larger programme of colonial development that included coordinated economic planning. From the mid-seventeenth century, the English state pursued tighter regulation of trade and settlement, bringing order out of the chaos of conquest and placing economic developments at the very heart of the emerging empire. During the 1640s, an alliance formed between opportunistic English aristocrats, such as Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick, and a new group of London merchants gathered around the slave-trader Maurice Thompson, who together pushed for an aggressively commercial foreign policy. From 1649 the new English republic, backed by this coalition, threw its weight behind both trade and empire. The republic used both commercial legislation and military force to promote overseas trade, serving metropolitan interests and giving English imperialism a new direction. The English also enthusiastically adopted innovative Dutch financial systems based on excise taxes and the creation of long-term public credit. Crucially, both Charles II, restored to the throne in 1660, and his brother James, Duke of York, understood the importance of this new approach in generating significant wealth for individual investors and for the English state from the proceeds of empire.

IRISH LAND PROVIDED SECURITY FOR IMPERIAL EXPANSION

When applied in Ireland, these policies allowed for the systematic exploitation of Irish resources for the benefit of England’s expanding Atlantic empire. Grants of large estates in Ireland provided English speculators with the necessary security to raise significant sums of money for investment in the rapidly expanding slave, sugar and tobacco trades, while Irish beef and butter fed the new plantations in the Americas and the Caribbean. The English empire would not have grown so dramatically in the late seventeenth/early eighteenth centuries without Ireland. It was the original jewel in the imperial crown. David Brown’s recent study of Adventurers for Irish Land underlines how central Ireland became to this new imperial strategy, one that laid the foundations for England’s and later Britain’s overseas expansion. The Cromwellian land settlement, imposed after military conquest, represented in many ways the last great seizure of resources in Ireland before England shifted towards exploiting the profits from a global network of trade. It provided the financial base for future imperial investment. William Petty’s great survey of Ireland turned the land itself into a commodity, deeply embedding Ireland within the structures of the British imperial world.

Despite this, British and US-based historians of empire, with a few notable exceptions, continue to ignore Ireland. Instead, the majority of scholars focus on the Western Design of 1655, England’s failed military campaign against Spanish interests in the Caribbean. The inadvertent capture of Jamaica that followed is presented as the defining moment in English imperial policy. According to this interpretive framework, England’s ‘consolation prize’ laid the foundations for a global commercial empire. Jack Greene goes as far as to claim that Jamaica was the first true colonial conquest carried out by the English state, overlooking the massive state-led conquest of Ireland only a few years earlier. For Carla Gardina Pestana, Jamaica marked the beginning of a more activist approach to empire, rooted in Cromwell’s belief that the state should take a central role in creating and sustaining imperial power. Pestana similar disregards Ireland, perhaps reflecting the unease many historians still feel about treating Ireland as a colony because of its European location. This persistent blind spot seriously distorts the imperial story. Before the Western Design expedition in 1654, England had already poured enormous resources into conquering Ireland, while Irish agricultural produce played a key role in maintaining English possessions in the Caribbean thereafter.

FRESH INTERPRETIVE FRAMEWORK NEEDED

What is needed now, therefore, is a fresh interpretive framework, one that places Ireland not at the margins but at the very heart of English imperial growth. From the mid-seventeenth century, Ireland supplied unprecedented financial and material capital, reinvested throughout the Atlantic, which drove the expansion of England’s empire. Charting these developments requires going back to the policies and practices in Ireland of the Commonwealth and Protectorate governments of the 1650s. By aligning the surviving records from Ireland with those from England’s colonies in the Americas and the Caribbean, historians can undertake a detailed comparative study that would be the first of its kind for the seventeenth-century English empire.

At the same time, revisiting Ireland’s role in the making of empire encourages us to think critically about the historiographical landscape. For too long Ireland has been treated as peripheral, left out of debates about England’s expansion in the Atlantic and beyond. Recognising its centrality forces us to see empire as something that happened not ‘out there’ in distant colonies but rather through entanglements closer to home, with Ireland as both a subject and a shaper of imperial ambitions. In an age when the legacies of empire continue to spark debates, from contested monuments to demands for reparations, the seventeenth-century origins require forensic analysis. The imperial project developed as a web of connections, formed through conquest, displacement, exploitation, commerce and migration. Ireland’s place in that web helps place the English empire in sharper focus and challenges us to confront the substantial human costs behind imperial power.

Micheál Ó Siochrú is Professor in Modern History at Trinity College, Dublin, and is Principal Investigator of the Research Ireland-funded Empire project.