Not many years ago, a popular BBC television series succeeded in making its audience experience an emotion that few could have thought would arise out of one of the greatest tragedies of this century, the First World War. This was to laugh at the efforts of Captain Blackadder to escape the inexorable folly of the General Staff, as it battled to move Field Marshal Haig’s drinks cabinet a few miles nearer to Berlin. Captain Blackadder invoked the British folk memory of the war as one of the ‘us’ against ‘them’—the ‘them’ being the General Staff rather than the Germans.

Symbol of battle between Unionism and Nationalism

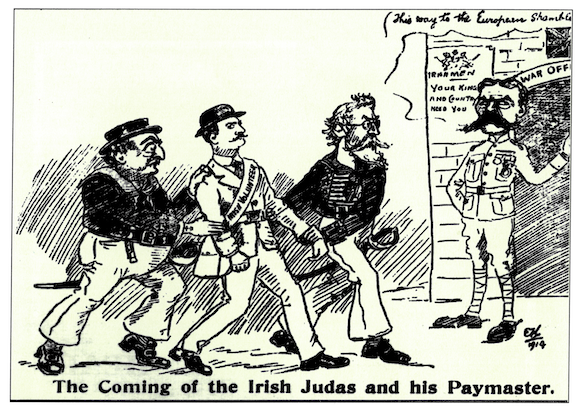

In Ireland the memory of war works on different levels. Here the memory is politicised. The Great War became a symbol of the battle between Unionism and Nationalism: indeed it was this from the beginning. While no one could doubt the desire of John Redmond and Sir Edward Carson to help Britain defeat Germany, both these leaders were aware of the conflict’s Irish dimension: that the sacrifice of life would make it hard for Britain on the one hand to renege on the implementation of the third Home Rule Act or on the other, to force it upon a recalcitrant Unionist Ulster. Unionist and Nationalist alike hoped that, as a Unionist poem put it, ‘England will not forget’. But, in case England did ‘forget’, one Unionist pointed out that ‘our men will be thoroughly trained, if necessity arises, to fight for our liberties, later on’.

The outcome is reflected in the history and indeed topography of Ireland. Hundreds of war memorials are scattered throughout the country; yet only in the North did they become rallying points for the reaffirmation of the traditions of a community. Elsewhere they bear witness, not to memory, but to official amnesia, as the guardians of the independent Irish state felt themselves obliged to forget those who rallied to Britain’s cause in August 1914 or to regard them as deluded survivors of an unworthy cause. Consider the celebrations of two seminal events in modern Irish history, the 1916 Rising, and the Battle of the Somme. In 1966 the Ulster Nationalist response to the Somme commemoration provoked rancour; in the south it was still possible to celebrate 1916 in such a way that even Trinity College Dublin graduates could wear their badge with pride. The Somme battle, in which thousands of Irish Catholic soldiers lost their lives, was by then successfully excised from the national memory.

The facts

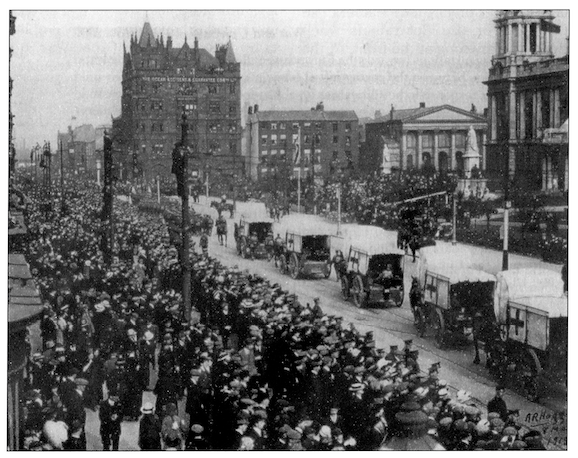

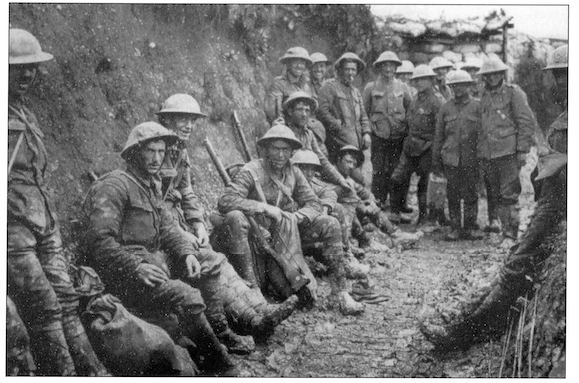

The historian interested in tracing the origins of political myths has to start off with the facts. After some initial (and much deserved) caution, both Carson and Redmond committed their respective volunteer armies, the UVF and the Irish Volunteers, to the British army, ill-trained for modern warfare as they were. Three divisions were formed, the 10th and 16th Irish, and the 36th Ulster. These divisions wore a common uniform, but they were utterly different in their religious, and therefore political, complexion. J. L. Stewart-Moore, a student at Trinity College, enlisted in the 12th battalion, Royal Irish Rifles (mainly recruited in Belfast) and soon found himself in the company of ‘working class lads who had left school at the age of twelve and had never been away from home before’, whose staunch Unionism and Protestantism was expressed in the singing of Orange ditties every night and the celebration of the ‘Twelfth’ with a khaki-clad King William mounted on a white horse.

The 10th and 16th Irish Divisions were almost exclusively Catholic (though with Protestant and Anglo-Irish officers—a reflection of the lack of Officer Training Corps in Catholic schools). Northern Ireland Nationalists were also mustered into these divisions. Not all joined for political or even military reasons; high unemployment in Irish towns and cities on the eve of the Great War provided incentive enough. Exact figures for Nationalist and Unionist recruitment are hard to find, but the best estimates put the total figure at around 116,972, of whom about 65,000 were Catholics and 53,000 Protestants, figures which were themselves not insignificant, as Nationalist and Unionist MPs vied with each other in demonstrating their loyalty to the British/Irish and British/Ulster cause. For the Nationalists, the war was a chance to raise their profile, to place them firmly in the ranks of the white Dominions, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and to get themselves on a level ground with the British and the Unionists. To do so, they were not averse to adopting the English stereotype of the Irish soldier as ‘the finest missile troops that we possess’: the gallant if hard to control Irishmen who stormed Badajoz in the Peninsular war in 1812 were paraded once again. But Nationalists also wished to emphasise the common name of Irishman, to demonstrate that the war was indeed forging an Irish nation, so that, as Willie Redmond put it in his book, Trench Pictures from France:

These young men came from the North of Ireland and from the South, with the famous Irish regiments… They professed different creeds; they held different views on politics and public affairs, but they were knitted and welded into one by a common cause. They fought side by side for their country. They died side by side…

In the House of Commons in March 1917, shortly before his own death in France, Redmond told how one Catholic officer who served with the Ulster Division discovered to his astonishment that ‘they certainly were Irishmen and were not Englishmen or Scotsmen’.

Common cause?

Was there any truth in this? There is evidence that common danger, common misery, produced some sense of fellow feeling. This may have been easier for southern Irish Unionists, whose relations with Catholics were always less tense and fearful than that of the Unionists of the North. Bryan Cooper, noting (correctly) that ‘beneath all superficial disagreements the English do possess a nature in common and look on things from the same point of view’, observed the miraculous transformation in Catholic-Protestant feeling in his battalion: ‘once we had tacitly agreed to let the past be buried we found thousands of points on which we agreed’. Englishmen, for their part, discovered that Catholic nationalists were not necessarily enemies of the Empire. Rowland Fielding, who transferred from the Brigade of Guards to the Connaught Rangers remarked how his ideas had changed, though it must be said that his attitude to his men revealed a reinforcement, rather than a weakening, of his racist view of the Irish as emotional, prone alike to easy elation and depression, ‘difficult to drive but easy to lead’.

This raises the central problem for the place of the Great War in Nationalist-Unionist and in Anglo-Irish relations. Rowland Fielding loved his men, but he hoped that Willie Redmond’s death in France would, as he put it, ‘teach all—North as well as South—something of the larger side of their duty to the Empire’. Britain wanted Ireland—all Ireland—to see the war from her perspective; Nationalists were willing to encourage this, but only at the (very reasonable) price of Home Rule; Unionists also, but only at the price of Sir Edward Carson’s demand, made in Bangor in 1916, that

Some nations must go down in this war. We are not going down… Yes, we have 17,000 rebels in camp now. God bless the rebels: these men who served in the trenches have given us time. How are we taking advantage of it? Today we may be able to do something; tomorrow the time may have passed. We are not a harum scarum lot of people gathered from here, there and everywhere. No, we are all brothers. They are our own Volunteers; they are men of our own religion. They are men of our own way of thinking: they are men of the great Ulster tradition.

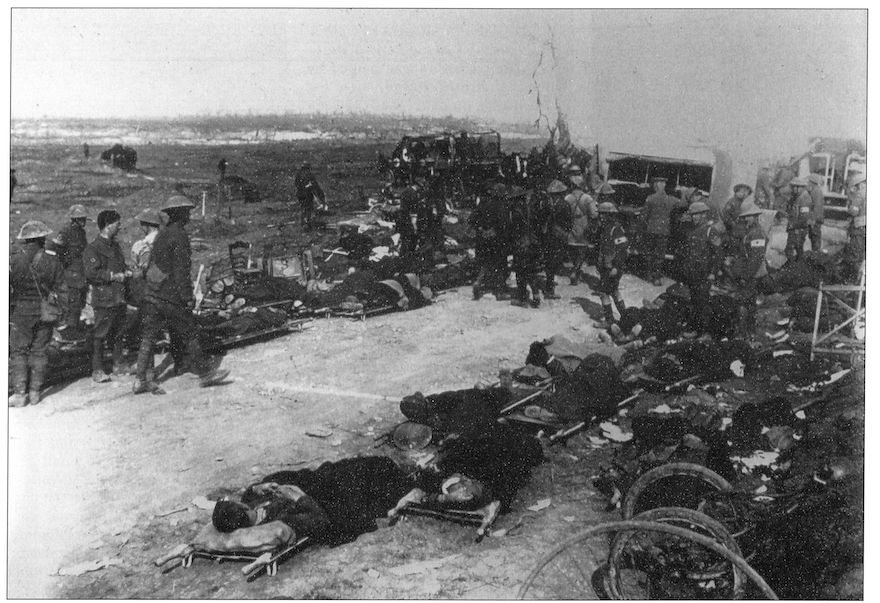

The Somme

The Unionist sense of community was given a focus in the Somme battle of the summer of 1916, which Cyril Falls caught in his history of the 36th Ulster Division. Falls noted that the Somme onslaught began on 1 July (old style calendar), and thus the 12th new style: ‘the sons of the victors in that battle, after eight generations, fought the great fight’. When Sir James Craig unveiled the memorial to the Ulster Division at Thiepval in November 1921 he disclosed a replica of Helen’s Tower in County Down, with the words ‘Ulster’s Love’ substituted for the original ‘Mother’s Love’, thus fusing the dedication of son to mother, son to native land. Here at last was what Ulster Unionism needed: a blood sacrifice to seal a community’s identity, indeed to create a sense of community amongst the disparate and in many ways divided Ulster Protestants. For Nationalist Ireland, the story was very different. 1916 was a sacrifice, but the sacrifice was made in Dublin, not in France. As Tom Kettle, staunch Home Ruler, believer in force to gain Ireland’s rights as a nation, put it: ‘These men will go down in history as heroes and martyrs, and I will go down—if I go down at all—as a bloody British officer’.

Kettle’s words can hardly fail to move us, even after nearly eighty years. The war was recrafted in the official Nationalist mind as the wrong war fought for the wrong cause. Irish ex-servicemen, many in number, were weak in political influence (for which the new Irish state had much cause to be grateful, for the role of embittered ex-soldiers in continental Europe is hardly one for a democratic state to envy). The transition was helped by that fact that for a decade after the war’s end the armistice was celebrated in some southern Irish towns and cities. In 1929 thousands of veterans marched in Phoenix Park and a representative of the Free State government laid a wreath. ‘God save the King’ was sung. Thus the Irish ex-servicemen, if not given a place in Irish history, were at least not subjected to hostile treatment. The new state’s early response to the war acted as a kind of field dressing for the ex-servicemen; but the coming to power of Eamon de Valera revealed that they were soon to be eliminated from the Irish public mind. A national war memorial, built through a mixture of public subscription and state funding, was designed by Edward Lutyens and sited at Islandbridge. De Valera at first agreed to attend its formal unveiling in 1939, but then withdrew his presence, despite those in his party who pointed out that such a ceremony could be treated as symbolical of the unification of all elements of the country under an agreed democratic constitution. The gesture could hardly fail to create a good impression beyond the border and upon British public opinion.

Myths

This was an over-optimistic point of view. Nevertheless, the Irish state’s withdrawal from the field left Ulster Unionists in possession of the folk memory. Recently, that memory has been the subject of historical investigation, and some at least of the myths surrounding it have been modified or dismissed. For example, the unhelpful British attitude to the 10th and 16th Irish Divisions can be explained not only by reference to official suspicion of Nationalist soldiers, but to the natural prejudice of professional soldiers, such as Sir Lawrence Parsons, commander of the 16th, against any political interference with the British military tradition of which he was a part. Parsons disliked what he called ‘silly’ innovations, such as a special divisional badge; and he opposed the commissioning of John Redmond’s son on the grounds that political influence should have no place in the army. He had aristocratic contempt, too, for the new men who all wanted to be commissioned as officers, rather than ‘be branded with “riff raff”‘, but who were themselves ‘quite socially impossible as officers—men who write their applications in red or green ink on a blank bill-head of a village shop’.

All this was unexceptional in the British Army of 1914. It was also usual for professionals to blame ‘inexperienced’ (i.e. non-English) soldiers like the Irish or the Australians when things went wrong at the front. At the same time, there was a, quite natural, tendency for the scapegoat nations to respond by creating new myths: that their soldiers were never afraid, never lost their nerves, and were always sacrificed by the British military establishment (which was pretty efficient at sacrificing the lives of its own men). A recent anthology of letters written by men of the 36th Ulster Division has contributed to dispelling such notions, and illustrates the ‘everyman’ approach to war studies, where the individual soldier is the focus of attention. Its editor, Philip Orr, acknowledged that men did run under the stress of battle, and attributed the Division’s initial success at the Somme not to superhuman ‘fire and aggression’, but to the Divisional HQ’s sound decision to order the advance before the artillery bombardment lifted, and thus before the German machine gunners could scramble out of their dug-outs. A new Somme Heritage Centre in Bangor, County Down, has as its aim the commemoration of the bravery of all Ulster’s soldiers, from whatever quarter they came.

Where history leads, literature follows. Or, rather, where politics follow, literature seeks to lead. The last few decades have seen a revival of literary interest in the Great War, no doubt inspired by the Ulster troubles and the search for identity that obsesses both communities in the North. The exploration of Irishness led naturally to a renewed interest in the war which was now perceived, rightly, if belatedly, as central to what Irishness or Ulsterness was—or, had events proved otherwise than they did, what they might have been.

How Many Miles to Babylon?

Jennifer Johnson published her novel How Many Miles to Babylon? in 1974 in order to focus on ‘a dwindling way of thinking about Ireland’. She hoped to build bridges, and saw the Great War ‘as a metaphor for what is presently happening. I was trying to write about human relationships with an undercurrent of violence’. Her novel was filmed, and in the course of the filming the past and the present, fact and fiction, blurred. Here was the spectacle of young men, dressed as Great War soldiers, marching around the Irish countryside:

I was talking to some of them, and I asked if any of their grandfathers fought in World War I. There was a very long silence while they all looked at me, and then one of them said, Yes, my grandfather was a Connaught Ranger. Another said, I had a great uncle, and somebody else said he had somebody in it. Suddenly you realised that they wouldn’t admit it to each other. Of course they all had connections with the Great War. It didn’t mean that their grandfathers were worse or better Irish men. It meant that they were, in their own way, small heroes.

The novel concerns the relationship between an Anglo-Irishman and a Sinn Féiner, between a member of the gentry class and a young Catholic stable boy, whose sense of Irishness is reinforced, not only by their experience in the trenches, but by their English officer’s attitude to them and to his indignity of being posted to an Irish regiment: ‘I never asked for a bunch of damn bog Irish’. Major Glendinning’s malevolence takes a tragic form when he orders the Anglo-Irishman to head a firing squad that will execute the Catholic for (temporary) desertion. Alec uses his revolver to shoot his friend, thus sparing him the ignominy of the firing squad; now he awaits his own death by firing squad: ‘they will never understand’. Mutual estrangement between Anglo-Irishman and Nationalist is symbolic of the wider cultural gap in Ireland, though we are not sure if the growing affection between the two would have survived the end of the war, Jerry, the Sinn Féiner’s, war of liberation would have meant that ‘every town, every village, will be a front line’. And the novel is essentially an Anglo-Irish novel, with no Ulster presence.

Observe the sons of Ulster marching towards the Somme

Frank McGuinness tries to explore what was to him an alien tradition in his play Observe the sons of Ulster marching towards the Somme. He believed that his position as an outsider would help him strive harder, and more successfully, to uncover the origins of a myth, which is not the battle of the Somme—an only too awful reality—but its use as a symbol of a whole community, united by that tragedy, reaffirming its identity through that historical experience. The play explains how Kenneth Pyper, the least committed, least typical of the Ulster soldiers, is drawn, despite his cynicism and his homosexuality (which makes him even more of an outsider) into the sense of oneness as they approach their great sacrifice. Pyper it is who, on the eve of battle, reminds the others of their homeland: ‘We’ve come home’. Pyper accepts the gift of an Orange sash, thus embracing not only his present, but his future destiny: ‘Let this day at the Somme be as glorious in the memory of Ulster as that day at the Boyne, when you scattered our enemies. Lead us back from this exile’. He finds the words that make the myth:

I love–observe the sons of Ulster marching towards the Somme. I love their lives. I love my own life. I love my home. I love my Ulster.

McGuinness sees this cry descending, not to the end that Pyper and his comrades hope for, but to a lonely, cold, distracted Ulster, where the temple of the Lord is ransacked. The play might then be seen as undermining Ulster Unionism and its myth, which on one level it is. But it also reveals the way in which sectarianism is lifted above rancour by the men’s pairing and bonding, their humanity, the desperation of their fate, and above all, by their energy and humour. These are real soldiers, expressing all the contradictions of their beliefs, and the vitality of their culture.

‘In Memoriam, Francis Ledwidge’

Contradictions are an essential part of the Irish condition, Unionist and Nationalist. Seamus Heaney sought to explore these in his poem ‘In Memoriam, Francis Ledwidge’, inspired by the Catholic soldier who served in the British army for the sake of Ireland, or of his kind of Ireland: ‘A haunted Catholic face, pallid and brave/ghosting the trenches with a bloom of hawthorn’. Ledwidge is buried, dead and gone like the ‘true blue ones’ whose memory is cast in bronze on Portstewart promenade, and the ‘strains criss-cross in useless equilibrium’. All of them now ‘consort underground’. But do they? Ledwidge and his kind were as divided from the ‘true blues’ ‘underground’ as they were when alive, their Orange and Green traditions separated by their sacrifices and by the way in which posterity has adopted, or abandoned, their memories.

Conclusion

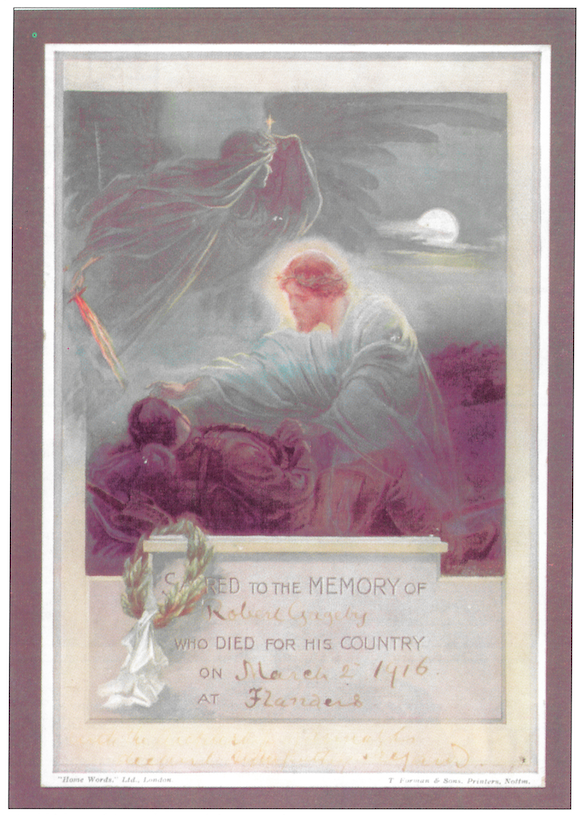

An historical study of the Great War shows that this was a turning point in the making of modem Ireland, and of Irish and Ulster identities. But one of the most important characteristics of those identities is ambivalence. The Catholic Irish soldier answered the call of Faith and Fatherland and also King and Country; so did the Ulster Protestant soldier. But neither could be certain that these would prove, in the end, compatible loyalties. As W.B. Yeats wrote, in his poem on the 1916 Rising, ‘England may keep faith’. That qualified opinion was one that neither the Ulster nor the Irish divisions, nor their political advocates, could expel from their minds. On my wall is a framed certificate, awarded to John F. Nixey of Belfast, who enlisted on 4 August 1914 ‘to defend the liberty of his country’. In these few words lie the great enigmas of modern Ireland: Whose liberty? What country? These questions are still no nearer resolution today than they were when the guns of August first sounded so many years ago.

George Boyce is Professor in the Department of Politics, University of Wales, Swansea.

Further reading:

K. Jeffery, ‘The Great War in Modem Irish Memory’, in T.G. Fraser and K. Jeffery (eds.), Men, Women and War (Dublin 1993).

G. Boyce, The Sure Confusing Drum: Ireland and the First World War (Swansea 1993).

Johnstone, Orange, Green and Khaki: The Story of the Irish Regiments in the Great War 1914-1918 (Dublin 1992).

P. Orr, The Road to the Somme: Men of the Ulster Division tell their Story (Belfast 1987).

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.