By Van Gosse

As an American historian, I am investigating Irish understandings of the United States’ system of white supremacy and race in general. My perspective is different from that of Irish scholars. ‘Racism’ in Ireland encompasses what Americans call ‘nativism’, as in fear of immigrants. In the US it developed via a black/white binary rooted in racial capitalism, eliding other ethno-racialisms, whether genocidal policies towards indigenous peoples, exclusion of Asians or Hibernophobia.

QUESTIONS

I began with questions. Did Irish people know how ‘Jim Crow’ functioned in the US? How did they see African Americans or Black people? Did Irish anti-colonialism generate anti-racist sensibilities? What I found is deeply paradoxical. On the one hand, an unembarrassed racism pervaded Irish public discourse. The ‘n’-word featured in Oireachtas speeches and newspapers into the 1980s, and yet much of Irish society found overt racism repugnant, unchristian, ‘un-Irish’.

There are two provisos. First, the fraught relationship of Irish Americans and African Americans was invisible in Ireland. Abroad in Boston or Brooklyn, ‘Irishmen’ either ignored or embraced Jim Crow. They had ‘become white’, focused on self-advancement in Protestant America, which Irish newspapers reported in enormous detail. African Americans, however, knew Irish Americans as notoriously racist. In 1921 W.E.B. Du Bois wrote to the head of the Catholic Board for Mission Work Among the Colored People that ‘there can be no doubt of the hostility of a large proportion of Irish Americans towards Negroes … I have found very few of them who have expressed the slightest sympathy for the Negro’. Second, for many founders of the Irish state, the racial issue was antipathy between Ulster Protestants and Catholic ‘Gaels’. ‘We have racial and language problems in regard to a divided country’, UCD Professor William Magennis told the Dáil in 1925, as Ulstermen were ‘filled with racial pride [and had] always treated the Nationalists and Catholics … pretty much as the n––––– was treated in the southern United States’. As late as 1946, Fine Gael’s Eamonn Coogan, imagining partition’s end, declared that ‘whatever their racial origins may have been [the Ulstermen] are Irishmen’. Only in 1960 did the moderniser Seán Lemass finally poo-poo the ‘long-discredited notion’ of two races in Ireland as ‘an historical absurdity’.

THE ‘N’ WORD IN THE DÁIL

I turn now to the word we no longer spell out. It was long part of ordinary speech, with the expressions ‘work like a n–––––’ or ‘a n––––– in the woodpile’ appearing without demur in newspapers and Leinster House debates. In 1987 Arthur Spring caused a flurry by asserting that his brother Dick, Labour Party leader and tánaiste, ‘has worked like a n––––– for North Kerry’, and in 2006 Seanad leader Mary O’Rourke declared that her supporters had ‘worked like blacks’. Its most common use, however, was in print advertising, where the words ‘n––––– brown’ or just ‘n–––––’ were ubiquitous as a standard colour for apparel.

In the Oireachtas, demeaning allusions to Black people were rife. The most notorious was Fianna Fáil’s Martin Corry, representing Cork from 1927 to 1969. In 1928 he denounced the government: ‘These [ministerial] salaries of £1,500 have to be paid so that they might squat like the n––––– when he put on the black silk hat and the swallow-tail coat and went out and said he was an English gentleman’, adding in 1930 that it was hardly ‘fit to govern even a tribe of African n–––––s’. He used this language for decades. As chairman of the Irish Sugar Beet Growers’ Association from 1948, he constantly railed against competition from Cuban, Jamaican or even Formosan ‘n–––––s’. Only in 1966 did Labour leader Brendan Corish confront Corry. The latter had declared: ‘We never fought in this country to have a foreign n––––– getting £12 a ton more for his sugar than an Irish farmer’. Corish rebuked him: ‘I do not think he should be allowed to describe people who are not of the same colour as people in this country as n–––––s’, only to have the leas-cheann comhairle rule that ‘“n–––––s” is not a disorderly word’.

Corish had broken with his party’s history, as William Norton, his predecessor as Labour leader (1932–60), used the ‘n’-word casually while deploring Ireland’s status as ‘the only white nation in the world to lose its population’ through ongoing emigration. Evoking whiteness had deep roots. Bruce Nelson’s Irish nationalists and the making of the Irish race examines how Irish Parliamentary Party leaders John Redmond and Isaac Butt long cast Ireland as ‘the only white race in the Empire denied the right to govern herself’. Eamon de Valera took up their claim in his 1920 ‘Appeal to the Conscience of the United States’, describing Ireland as ‘the last white nation deprived of its liberty’. While Ireland’s fight for freedom exerted ‘a magnetic attraction for men and women of colour throughout the British Empire’, their solidarity was intermittently reciprocated. Minister for Justice and External Affairs Kevin O’Higgins expressed many Sinn Féiners’ racial politics in January 1923, justifying the Provisional Government’s suppression of the anti-Treaty IRA by insisting that otherwise ‘we bid fair to be classed with the n––––– and the Mexican, as a people unable to govern themselves’.

Norton was not the only leader to champion whiteness. In March 1944 Clann na Talmhan’s founder, William O’Donnell, defended his impoverished Tipperary constituents: ‘We have been called hewers of wood and drawers of water, but we do not deserve the name of the dirty Irish. There are farmers who are obliged to work like negroes in order to provide their houses with a sufficiency of water.’ He added four months later: ‘I would say that the streams of Ireland, most of them, are little better than polluted sewers. We must be a healthy race to exist at all. We must be healthier than the n–––––s to survive … It is the whitest of white slavery.’ (In 1961 the Clann’s Michael Donnelan denounced Lemass’s industrial policy as ‘a few Japs, a few Jews, or a few Negroes [will] come in here for the taxpayers to build factories for them, contribute to the cost of their machinery, give them slave labour’—a nonsensical claim.)

Fine Gael leader James Dillon used the term ‘work like a n–––––’ for decades. Oddly, one of his predecessors, W.T. Cosgrave, alone linked Irish and Black freedom struggles, asking in 1932 why, ‘when we are simply asking to be allowed to maintain our right to govern ourselves in our own way … [should we] be accused of egotistic nationalism? … It is similar to what might have operated, let us say, in the Southern States of America when the subject negroes there asserted their God-given rights to act independently and not to be the slaves and chattels of other individuals.’

‘SLAVERY’

Cosgrave’s acknowledgement of Black humanity was exceptional. Usually American slavery featured only as a trope for how ‘slavery’ under British rule, or ‘wage slavery’ in the present, was much worse. In 1944 the aged socialist James Larkin, defending the rural proletariat, asserted that slavery ‘was the correct word’ for their condition, adding that: ‘The negro slaves in America were far freer than the ordinary worker in the agricultural area who has to seek his daily bread. At least, the negro slave had to be fed. He could be whipped and harassed, but he had an assured shelter and an assured measure of food.’ In 1938 Senator Thomas Condon described many Irish people ‘living under serf conditions or in slave conditions … their position is really worse than that which existed under the old slave conditions’, hailing the notoriously pro-slavery exile John Mitchel as ‘a man of extraordinary vision … To-day you have in the world much worse conditions than the slave conditions of the American negroes.’ Ireland’s connection to transatlantic abolitionism—Frederick Douglass and other Black abolitionists toured Ireland, and Daniel O’Connell campaigned against slavery—was forgotten until recently.

In contrast, the Irish press rarely featured open race-baiting. America’s racial terror was uniformly presented as barbaric, a rebuke to the vaunting Yankees (‘American justice mocked … 3 negroes burned at stake in Texas’). Through the 1930s the focus was on violence inflicted on Black people, with regular coverage of lynchings emphasising their brutality (the auto-da-fé aspect drew particular revulsion). During the Scottsboro trials, the viciousness of condemning teenage boys to death over and over (‘Six years under sentence of death’ or ‘sentenced to death third time’) was excoriated. An April 1935 comment in the Irish Times summed up the ‘general attitude towards negroes in America’ as one of ‘race-hatred … seeing them as a “black beast” to be hanged or burnt alive’. However strong the pride over the country’s lack of racism (‘Here in Ireland the existence of such a thing as a colour bar is hardly known’, the Cork Examiner proclaimed in 1949), Jim Crow itself was far away. Any division into groups was derided as ‘Jim Crow tactics’. In 1951 Minister for Health Noel Browne’s proposal to treat ‘the sick poor’ at home was labelled ‘Jim Crow laws’. Four years later, Myles na Gopaleen, describing his time in hospital, found ‘a sort of Jim Crow atmosphere in those places. Segregation is enforced, and I was one of twelve patients in a small ward, all males.’

The emphasis shifted after 1945. In 1946 the Irish Times noted that ‘Hitler’s savage persecution of the Jews has led to a violent revulsion’ against racism. In 1948 The Leader suggested that the ‘great outcry’ over the Holocaust ‘overshadowed the equally unjust … ostracization of the negro’ in the US, which ‘made a mockery of representative democracy and … the principle of equality before the law’. As the Cold War heated up, the Irish Times underlined the international implications, that ‘every friend of America and humanity’ recognised that white supremacy was ‘a blot upon civilization, and while “Jim Crowism” persists, the United States cannot claim to be the standard-bearer for true democracy … Lynchings and other barbarities … differ only in degree … from Hitler’s treatment of the Jews.’ Irish editorialists also often compared America’s apartheid system to South Africa, spurred by debates at the United Nations.

Regarding the US, Black agency rather than victimhood was now the leitmotif, with coverage in presidential years emphasising African Americans as the ‘balance of power’ between parties. The Echo noted approvingly in 1956 that ‘coloured people have leaders with a sharp intelligence and a good sense of responsibility’, who seek ‘to become as powerful an influence on the attitude towards negroes as the Irish in the States’. The civil rights movement received admiring treatment, emphasising religious leaders like Martin Luther King Jr.

ANTI-COLONIALISM

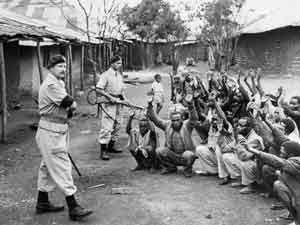

Slowly, anti-colonialism qua anti-racism intruded into Oireachtas debates, via decolonisation in Africa. As early as 1952, Labour’s Seán Dunne urged the taoiseach to denounce the ‘purgatory’ that the British were inflicting on Kenyans to suppress the Mau Mau rebellion. In the late 1950s, avowed anti-racialism came to the fore from left-wingers like Noel Browne, while Minister for External Affairs Frank Aiken drew international praise for attacking colonialism in the UN, and Ireland stood out as the first country in Europe to oppose apartheid in South Africa.

One constant was adulation of individual African Americans, whether athletes or singers. The Irish Press’s ‘Permel’ was awestruck when interviewing Jesse Owens at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, calling him ‘a great athlete, a great sport, and a great gentleman’, while oblivious to the event’s racial politics, reporting days later on ‘the honour of getting a few words’ with Josef Goebbels at a Nazi reception. Paul Robeson, then the best-known Black man in the world, received the same naïve admiration as the ‘brilliant negro actor’, with ‘exceptional gifts … world-famous’. An Evening Herald reporter interviewing him at the Shelbourne during a triumphal 1935 visit used the same language as for Owens, calling him ‘a negro gentleman’.

Esteem for Robeson only grew when he became a prominent victim of America’s Red Scare. Among white Americans Robeson was reviled. Coverage of his travails in Irish newspapers offers a different perspective; as in the UK and Europe, he remained a star, regardless of his philo-Sovietism. In Ireland the focus was on the indecency of a government destroying a great artist, as the US took away Robeson’s passport so that he could not tour, and concert halls barred him. Irish papers closely followed the long battle to regain his passport, tracking support from the British labour movement and his rapturous reception on reaching the UK in 1958—appearing before 150,000 people at the Welsh National Eisteddfod; singing for 4,000 at St Paul’s; invited to perform in Pericles at Stratford; and sold-out Belfast concerts. Robeson’s recording of Kevin Barry in 1957 added to his legend, with the Limerick Leader hailing ‘the magnificent recording … such a magnificent bass … worth every penny’.

Irish disdain for McCarthyism was one of many instances of claiming a moral high ground, as when a young Charles J. Haughey, presenting a Hotel Proprietors’ Bill in 1962, declared that ‘no Irish court would hold that colour would be a reasonable ground for refusing admission to any prospective guest … the Bill does … effectively ensure that we shall not have ever emerging in our Irish hotels any suggestion of a colour bar’. By the later 1970s, while some still used the ‘n’-word, overt racism was anachronistic, as liberals exemplified by Garret FitzGerald’s passionate anti-apartheid advocacy came to the fore. Like others on both sides of the Atlantic, the Irish preferred to forget how they had once championed whiteness. As protests escalate in the Republic against immigrant ‘others’, it would be well to consider this history. Whether in the US or Ireland, we all need to reckon with the legacies of racial exclusion.

Van Gosse is Professor of History at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Further reading

N. Ignatiev, How the Irish became white (London, 1995).

B. Nelson, Irish nationalists and the making of the Irish race (Princeton, 2012).

D.R. Roediger, Working toward whiteness—how America’s immigrants became white: the strange journey from Ellis Island to the suburbs (New York, 2018).

J.M. Skelly, Irish diplomacy at the United Nations: national interests and the international order (Newbridge, 1996).