By Mark Holan

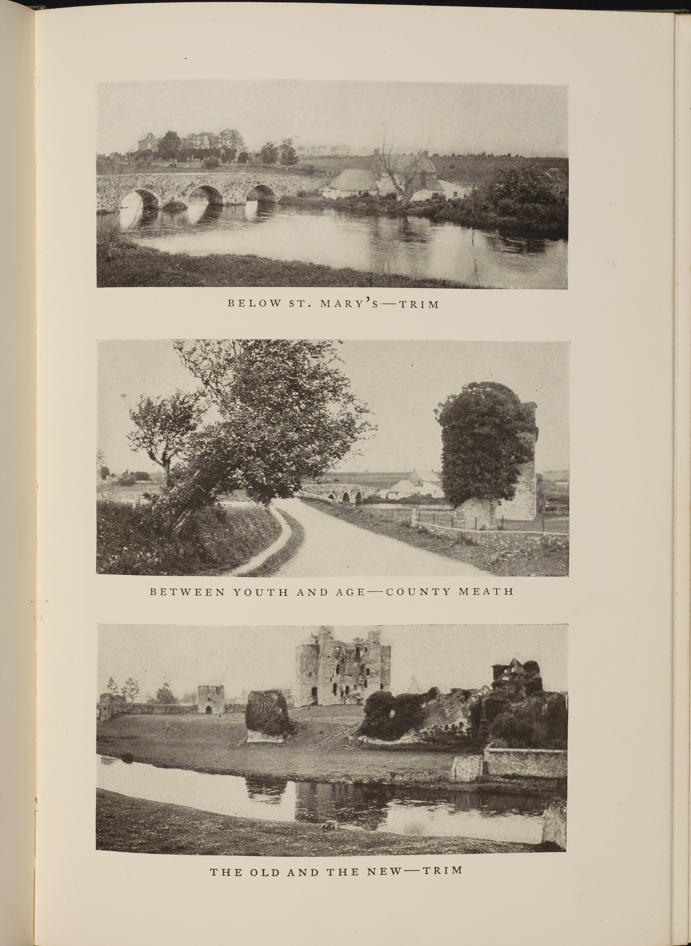

American photographer and antiquarian Wallace Nutting drove through all 32 counties of Ireland in the summer of 1925, taking some 700 images of the country. His travels resulted in the photobook Ireland beautiful, which was published in time for Christmas gift-giving. It featured 304 of Nutting’s half-tone engravings of Irish landscapes—only six images show people—and his text in support of the title. ‘This volume pretends to no place as a guide book, nor is its text intended to cover with precision or fullness any part of Ireland’, Nutting wrote from his studio in Framingham, Massachusetts, about 35km west of Boston. ‘It is merely a record of impression of beauty or quaintness, observed in a land which for romance and pathos, strange history and legend, for witching grace and mystery, is probably unsurpassed.’

Nutting’s book coincided with efforts to redevelop the Irish economy in the wake of the First World War, the War of Independence and the Civil War. Those events, spread over a decade, ‘had a catastrophic effect’ on the tourism industry, Eric G.E. Zuelow wrote in a 2009 assessment. The Irish Free State government and the revitalised Irish Tourist Association (ITA) sought to promote the country’s natural beauty and innate hospitality to visitors from key markets, especially the United States. American journalists and business leaders assured these Irish officials that tourism had tremendous potential for success.

As Nutting motored around the countryside, he joined ‘the highest types of Irish American successful business and professional classes, many of whom are visiting Ireland for the first time’, as Robert Lindsay Crawford, the Free State’s New York City-based trade representative, wrote to Timothy A. Smiddy, the state’s emissary to the US government. In his July 1925 memorandum, Crawford estimated that 10,000 Americans and Canadians would spend ‘in the neighbourhood of $3 million’ by the end of the year in Ireland. That’s about $55 million today, factoring in a century of inflation, or less than 1% of the Republic’s current annual tourism revenues of €6 billion ($6.2 billion).

OTHER DEVELOPMENTS

In addition to Ireland beautiful, two other 1925 developments boosted Irish tourism from America, as Smiddy detailed from Washington DC to Minister for External Affairs Desmond FitzGerald in Dublin. One was a Fox Film Corporation newsreel of Irish scenery; the other was the silent comedy-drama film Irish Luck. In the latter, a New York City traffic cop wins a newspaper contest for—what else?—a free trip to Ireland. ‘Nothing is more calculated to advertise good features of Ireland than publicity of this character’, Smiddy wrote in December 1925. The following month ITA president Howard S. Harrington arrived in America to further publicise Ireland. Ireland beautiful, he later told association members, was ‘the most effective’ of the three mass media developments cited by Smiddy.

Harrington is not named in Nutting’s book but is almost certainly the ‘American of distinction’ whom the author described as having ‘brought his wealth to crown his love for Ireland’ and ‘reassumed his ancestral castle’ to carry out ‘the finer dreams of his ancestors’. Harrington, a New York-born maritime lawyer who represented US shipping interests from London during the Great War, purchased Dunloe Castle and surrounding acreage in Killarney as separatist rebels and British forces were still shooting at each other.

IS IRELAND SAFE?

During his US visit, Harrington assured the New York Times that ‘permanent peace has dawned in Ireland’. He also acknowledged that ‘it will require considerable time to wipe out the vestiges of the hectic years preceding this period’.

While the violence had ceased, lingering political bitterness and the uncertainties of partition added to the island’s economic challenges. In February 1925 the international press published stories—and photos—that purported to show that the Free State’s western seaboard had once again plunged into famine. The September 1925 premier issue of Irish Travel, the ITA’s official organ, picked up the story from there:

‘Some months later still wilder stories of shootings from the housetops in Dublin and other Irish cities were in circulation in some American newspapers. But all these wild stories were contradicted as fast as they appeared. The American press is sensitive to the value of news from Ireland, and it finds out the truth very quickly. Naturally enough, newspapers which carry the wild stories do not display the contradictions of their own “exclusive scoops”, but other papers do, and the American reader soon learns the truth about happenings in Ireland and elsewhere.’

Irish Travel returned to these concerns in its November 1925 issue under the headline ‘Is Ireland Safe?’ The story insisted that ‘Ireland is perhaps the most peaceful country in the world today’ and ‘it is ridiculous to suggest that Ireland is not a safe place for any visitor’.

Nutting confirmed this positive view in Ireland beautiful. ‘Peace reigns in the land’, he enthused. ‘Americans are received with the greatest heartiness.’ In an autobiography published eleven years later, Nutting revealed that an English photographer who ‘barely escaped’ the violence of the Irish rebellion had warned him to avoid the country in 1925, but he reiterated that Ireland had been friendly and trouble-free during his visit.

TOURISM TRADE

The ITA’s post-war efforts were not the beginning of the Irish tourism industry. The island was promoted in the Grand Tours of the eighteenth century. German journalist Richard Arnold Bermann arrived in 1913, just before the Great War and revolutionary period. He was sceptical of mass tourism in general and disdainful of American tourists in particular. ‘At this moment in time tourism is really taking off in Ireland’, Bermann wrote. ‘It will not exactly do away with the country’s history because it feeds on it—Ireland’s history populates the countryside with splendid sights, with druidic stones, with ancient kings and ruins in every shape and size, all meticulously decorated in ivy. But the tourist industry should help clear the huts, these dreadful holes, even if then the ladies from Connecticut or thereabouts find Ireland a lot less delightful.’

Ireland beautiful book-ended Bermann’s Ireland [1913]. Nutting agreed that Americans had plenty of money to spend in Ireland. He predicted that ‘if the department of intelligence is well managed, the tourist in Ireland should increase hundred fold’.

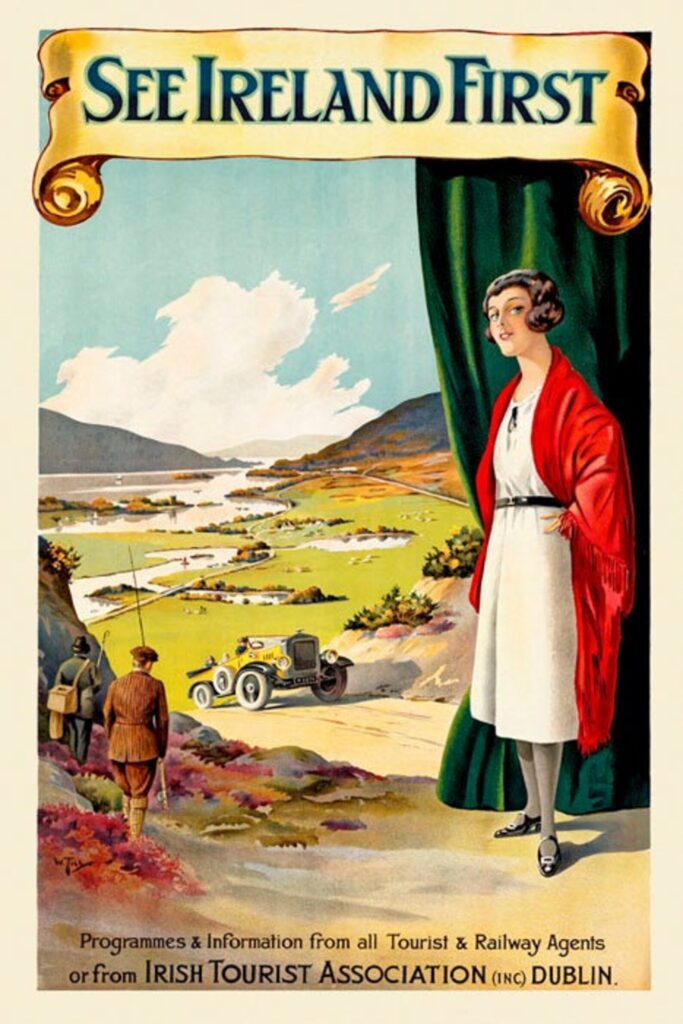

Still, growth couldn’t be taken for granted. In his July 1925 memo, Crawford warned that US advertising executives ‘severely criticized’ ITA’s ‘See Ireland First’ travel poster (p. 34) as ‘lacking in artistic and advertising qualities’. Tourism promotion needed to be more sophisticated, and hospitality infrastructure needed to be upgraded. Nutting cautioned Americans to seek overnight accommodations in larger towns or resorts because appropriate lodging was difficult to find in villages and remote areas.

Nutting was 65 when he visited Ireland with his wife. He claimed that they drove 7,000 miles during their seven-week stay. That averages 140 miles per day, a seeming contradiction of the author’s advice that ‘a hundred miles a day is always too much’. He suggested that visitors plan to drive 30–40 miles for ‘getting ahead’, while an equal number of additional miles ‘should be expected’ in detours. But he had few complaints about road conditions. The ‘greatest mistake’ for a traveller in Ireland, Nutting warned, ‘is to go rapidly’.

NO POLITICS OR RELIGION

Nutting insisted that his book had ‘nothing to do with political and religious matters’. Though he began his career as a Congregationalist minister, Nutting avoided any overt sectarianism. He suggested that the ‘untouched condition’ of Ireland’s Protestant churches refuted the notion of a ‘so-called’ religious war. ‘More often than not Protestant and Catholic, after a generation or two on the soil, have become intensely Irish’, he observed. Likewise, he steered away from political partisanship, making instead sweeping statements. ‘The people of Ulster were as insistent on remaining in the empire as South Ireland was on withdrawing from the empire’, he summarised. He happened to visit Belfast as Orangemen marched on 12 July. ‘We tread here on delicate ground, and can easily plead that we know too little to form a judgement’, he dodged.

Without naming the Boundary Commission, Nutting stated that ‘a cause of political tension just now is the determination of the bounds between the two governments’. He also suggested that the ‘undoubted and unchallenged continuance of Ireland as an independent government’ removed any reason for the Irish-language revival. ‘We of America are not in any danger of losing any aspect of our nationality through our use of the English speech. No more are the Irish in Ireland’, he said.

SECOND EDITION

Ireland beautiful included nearly 40 full-page images (vertical and horizontal) and pages with two, three or four photos. The book featured four poems by Mildred Hobbs, who contributed verse to Nutting’s other photobooks of US states. Her stanzas offered the same treacly tropes as a St Patrick’s Day greeting card:

‘Irish lads and lasses know

Where the fairy hawthorns grow

For they’ve seen the little people

Nightly come and go.’

The book included a 75-entry glossary of Irish place-names and an index. ‘I cannot imagine a more acceptable book gift at Christmas for those who find joy in the contemplation of pulchritude, whether they claim kinship with Innisfail or not’, gushed a newspaper review in Nutting’s home state of Massachusetts.

Nutting republished Ireland beautiful in 1936. The second edition rearranged some photos at the front and back of the book. Notably, the image of a rose-bedecked cottage in Killarney opposite the title-page replaced an advertisement for Nutting’s other photobooks in the original edition. The author did not update his October 1925 Foreword or revise the text. His dedication remained: ‘To those Americans who, from birth, have loved or have learned to love old Ireland’.

Even as colour photography became ubiquitous, Nutting’s black-and-white images remained a template for romanticised presentations of ‘old Ireland’ throughout the twentieth century, notwithstanding the Troubles. Today, mass media and marketing have spurred record tourism growth to six million overseas visitors in 2024. It is seldom the case, as in Nutting’s day, that the traveller to Ireland ‘is not jostled by other sightseers’.

Mark Holan is an independent journalist and historian based in Washington DC.

Further reading

W. Nutting, Ireland beautiful (Framingham MA, 1925).

W. Nutting, Wallace Nutting’s biography (Framingham MA, 1936).

L. Wheatley & F. Krobb (trans & eds), Ireland [1913] by Richard Arnold Bermann (Cork, 2021).

E.G.E. Zuelow, Making Ireland Irish: tourism and national identity since the Irish Civil War (Syracuse NY, 2009).