JOSEPH BRADY and PAUL FERGUSON

Birlinn

£30

ISBN 9781780279640

Reviewed by

Thomas O’Loughlin

Thomas O’Loughlin is Professor Emeritus of Historical Theology at the University of Nottingham.

Books involving mapping can invariably be located on a simple grid of two axes. On the horizonal axis there are the notional extremes of the history of cartography—i.e. the process of map-making and so of information-gathering (in recent centuries this focuses on survey)—and, at the opposite pole, the history of maps, the graphic objects that can be held, bought, sold, stored, admired or criticised for their in-utility or ugliness. On the vertical axis the poles are whether to view the map as a product of the intellectual world in which it was created—and so part of that world’s sociology of knowledge—or as a simple recording of objects in the material world in their spatial relationships through a set of symbols. This book can be located very comfortably and distinctly within this grid: it is about maps of objects in the world.

It says in the foreword that ‘it does not aim to be … a history of map-making. Rather, it is about the maps themselves’—and, indeed, it has already given us a clue to its approach in saying that the relationships of objects in the spatial world often only ‘becomes apparent when it is possible to look at these things on a good map’. Ah! A good map! But what, for the historian, constitutes a good map? Is it a valuable historical document that is revealing, or is it a product of survey, or is it a modern map drawn by/for the historian that adequately conveys the historian’s information? Further on in the foreword the authors note that the work of the Ordnance Survey (OS) ‘quickly became the gold standard in mapping’, but this sees topographical comprehension, and with it planimetric accuracy, as the fundamental criterion for maps/good maps. Nevertheless, if the book is firmly in the ‘objects in the world’ box, we should note that most of the maps actually presented either do not conform to this ‘gold standard’ (e.g. the fascinating, and virtually unknown, propaganda map on p. 67 from c. 1919–20 of ‘the Irish Republic’, where, ‘God [having] Fixed the Boundaries of Ireland’, it is as much a geographical claim as the election returns of December 1918) or else what makes them interesting is not dependent on their locational accuracy (e.g. the U-boat map on p. 249 or the Soviet maps on pp 250–1). The history of cartography/maps is never a simple business. To see this complexity, it is worth looking at, as a case-study, G.H. Herb, Under the map of Germany: nationalism and propaganda 1918–1945 (London, 1997).

Given that the book focuses on maps, it is not surprising that after a quick shuffle through the Middle Ages it arrives at the maps from the age of printing, with a fine selection of really interesting examples. The maps of Sir William Petty get a special accolade, for with him the island’s shape becomes the one we know today (p. 26). There follow chapters on boundaries, maps and the economy (be it for geology or for tourism—with a fascinating but not directly relevant excursion into the history of cigarette cards on pp 239–44) and a detailed study of the works of the OS either as topography or in other government service.

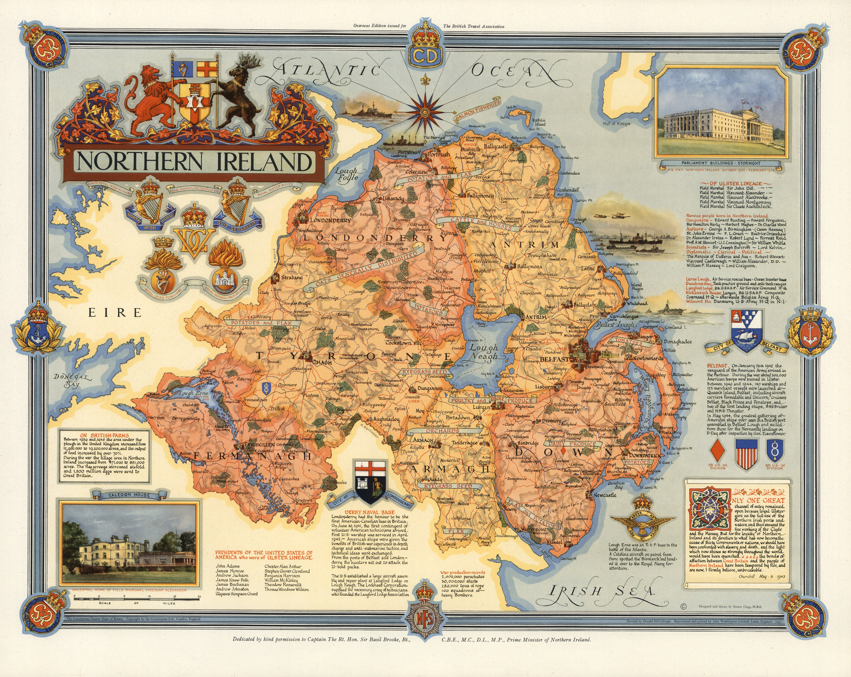

I would draw attention to just two specific maps that bring out the value and weakness of this book’s approach. The first case is a map of ‘Northern Ireland’—probably the most elegant item, graphically, in the book—that is used as a frontispiece (p. viii) and then reproduced in full on pp 153–4. Produced in 1947, it is anything but a map in the ‘spatial objects’ sense but rather a plea to a British public (and to a lesser extent an American public) for recognition of the UK identity of Northern Ireland. This unity—there is no hint that there is any questioning of the UK identity, much less of dissent from it—is wholly unconnected from the contiguous land, simply labelled ‘EIRE’ (sic), while every link (e.g. regimental badges) with Britain, every service in the war effort (e.g. lists of officers with family links) and every product supplied (e.g. oats and cattle) are presented with calligraphy. It is full of information, yet its silences are even louder. But, while we are grateful to the authors for presenting it, we are faced with an enigma: this map, unlike almost every other in the book, is not commented upon in the text. Moreover, the authors say that they wish to help readers become more map-aware—bravo!—but surely here is the place to introduce the tradition of commentary begun by J.B. Harley (‘Deconstructing the map’, Cartographica 26 (1989), 1–20, and reprinted in P. Laxton (ed.), The new nature of maps: essays in the history of cartography (Baltimore, MD, 2001), 149–68; this work is not mentioned anywhere in the book under review) when he decoded an even ‘simpler’ (apparently) map of North Carolina. This map of ‘Northern Ireland’ begs for a similar analysis.

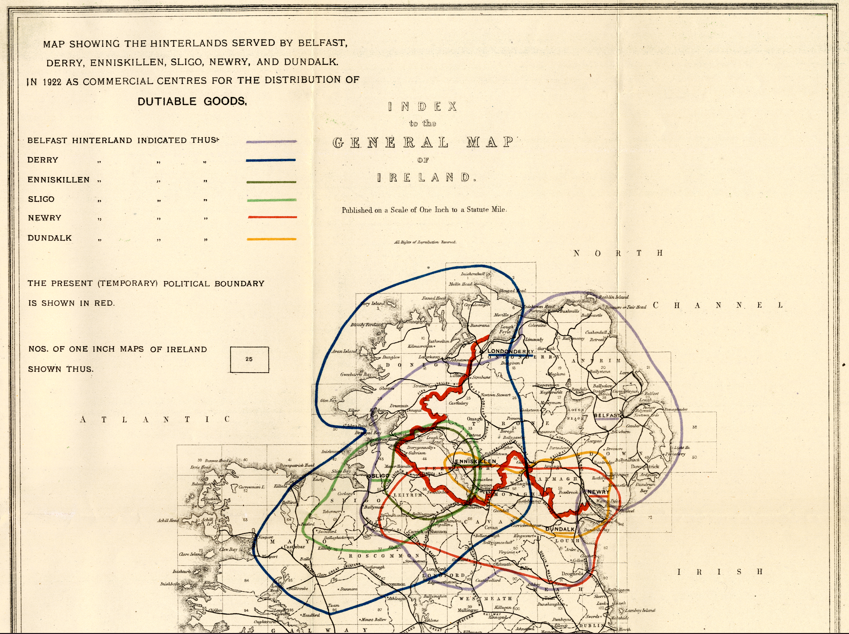

The second map is that produced by the Irish government in 1923 showing how the then-proposed border in Ulster cut through the natural economic hinterlands of many places reaching from north Galway to Donegal. It is a very simple map graphically, but a classic case of how maps convey information that cannot be put into words. It is one of a set of five (three are produced here, on pp 69–72) that show us how much work there is to be done on the history of Irish mapping (in every sense) and, indeed, how much more use historians can make of maps as primary historical evidence. For bringing this topic to our attention and reminding us just how much work remains to be done, we are in these authors’ debt.