by Donard de Cogan

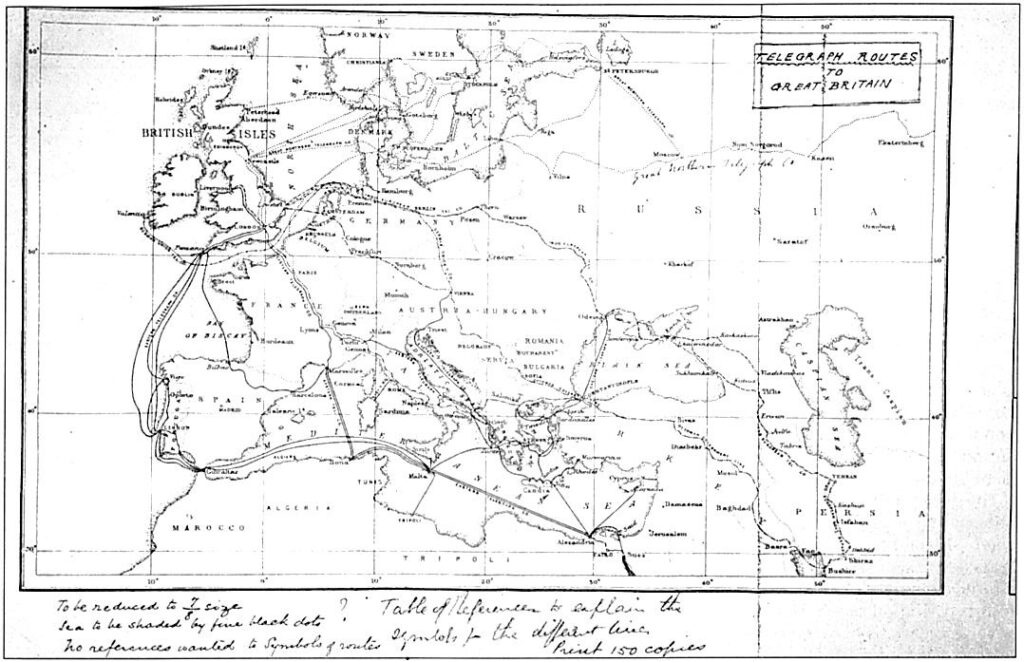

The electric telegraph was invented in 1837 and proved to be an instant success. It provided new possibilities for the rapid transmission of news and business information. International communications required the use of insulated electrical conductors and the first techniques for coating copper wires with a suitable material were patented by Siemens Brothers in Prussia. Henry Bewley of Dublin provided an alternative method of insulation which laid the foundations for British domination of the submarine cable industry. The new cables from Britain to Europe were first used for commercial purposes with very little government intervention. The promoters saw enormous financial benefits in being able to communicate with Summer 1993 America and by the mid 1850s there were moves to establish a transatlantic telegraph link. This was new technology fraught with potential problems. Chief amongst these was the uncertainty that electricity could travel that distance or be sustained under the terrific pressure of deep ocean. The shortest route was therefore essential and, as the Kerry coast was one of the westernmost parts of Europe, it was natural to start from there to Newfoundland, the equivalent easternmost part of north America. Attempts to lay cables in 1857 and 1858 were unsuccessful, leading to a severe loss of confidence amongst the financial backers: with the additional interruption of the American Civil War, it was not until 1866 that permanent communications were established from Valentia.

White Strand Ballycarbery Point on

the mainland near Valentia Island –

1857. (Left and top right)

(FROM THE COOKE COLLECTION OF DRAWINGS INTHE ARCHIVES OF THE INSTITUTION OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERS, LONDON)

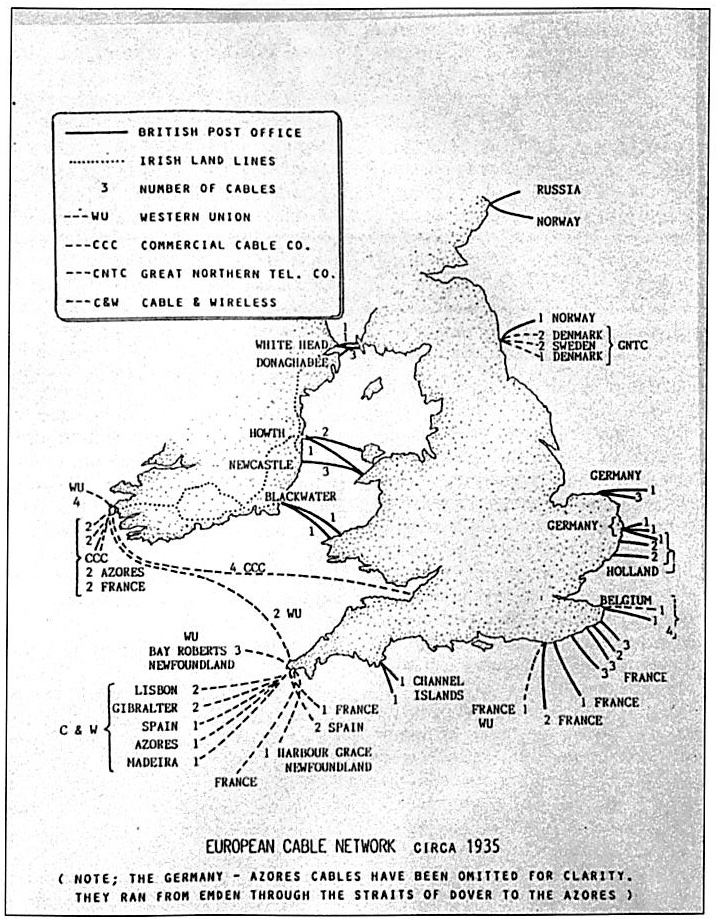

Commercial success soon led to competition and by the turn of the century there were links to Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Britain, France and Germany. Ballinskelligs station was opened in 1874 but was soon absorbed by the Anglo American Telegraph Co., who also owned the Valentia station. The Commercial Cable Co., which operated the Waterville station, was a wholly American company, founded by James Gordon-Bennett and John W. Mackay, an emigrant from Dublin who became a Nevada silver magnate and one of the richest men in America. It opened for business in 1885. As a result of a financial deal, Ballinskelligs and Valentia came under the control of the Western Union Telegraph Co. in 1911.

The telegraph and imperial rivalries

The British Treasury had subsidised some of the early attempts to get lines of communication to India and Canada and when these failed there was an effective moratorium on further funding. Thus, in contrast to other European countries, the expansion of the cable network in the 1870s was totally financed by private enterprise and within a very favourable financial environment. It was a successful technology: when the UK inland telegraph service came under Post Office control after nationalisation in 1871, the large release of capital was thereafter available for investment in new international ventures.

The telegraph played its part in imperial rivalries. There was shock when Bismarck precipitated the Franco-Prussian war by means of an altered telegram, but at least this reduced Anglo-French rivalries for several years. There were scares over Russian expansionist policies in 1878. A further scare in 1885 led to the establishment of the Colonial Defence Committee which recommended an All Red Route for the transmission of official government traffic. It also recommended that the cable network only land on Imperial soil or territory controlled by trusted friends (e.g. Portugal, Britain’s oldest ally); that the network should be duplicated in case of damage; that it should be operated by trusted staff only; and that censorship apply in times of crisis.

The basis for these recommendations was reinforced by several events in the late 1890s. There was much cable-cutting during the Spanish-American war and for a time it appeared that British lines of communication might be disrupted. The recommendations were used to good effect as tensions developed during the scramble for Africa. Both France and Germany had to communicate with their new possessions via British cables and on several occasions (such as the Fashoda incident: an Anglo-French military confrontation on the upper Nile in 1898) the inspection and ‘delay’ of messages were used to British diplomatic advantage.

Censorship

On 5 December 1913, the War Office drew up ‘Regulations for censorship of submarine cable communications throughout the British Empire’ which aimed to deny naval or military intelligence to the enemy; to prevent the spread of false reports likely to affect the morale of the civil population; to collect and distribute enemy information to government departments; to deny the use of British cables to any person or firm, British, allied or neutral for commercial transactions with the enemy; and to interfere as little as possible with legitimate British and neutral trade.

The Post Office was responsible for issuing, at the request of the War Office, the necessary notification to the International Telegraph Office; the issue of notification to the public; the establishment of temporary censorship at the Central Telegraph Office pending the establishment of censorship by military officers; maintaining a watch at the various cable repeater stations (whether belonging to the Post Office or the cable companies) with a view to guarding against any telegrams being sent or received at these places; providing assistants to the Chief Censor and the Deputy Chief Censor at the Central Telegraph Office; and generally taking all steps necessary to ensure that telegrams to and from places abroad passing over continental cables should be submitted to the censors.

At first sight one might perceive the possibility of legal problems since the Irish cable stations were operated by private companies. The Valentia station was owned by the Anglo American Telegraph Co. BalIinskelIigs was the Irish terminus of the Direct United States Telegraph Co., a British company which had been established to provide competition and to force down tariff rates. When it proved too successful it was bought out and absorbed by Anglo. At the other end the lines which fed traffic from Canada to the financial heartland of the United States were operated by the Western Union Telegraph Co. There was much concern when Waterville was opened in 1885 as its owner, the Commercial Cable Co., was wholly American owned and had a direct line from Waterville to France which avoided transit through Britain. The apparent extent of British control seemed to decrease even more when operational control of Valentia and BallinskelIigs passed to Western Union in 1911. However, the private operations valued the license to land cables on Imperial soil and were prepared to comply with whatever conditions the government laid down.

The Irish cable stations at war

The first world war brought chaos to the Irish cable stations. The volume of government traffic increased dramatically. Censors were installed and were mainly retired army officers with very little experience of cable communications and technicalities. Although at a later stage some civilians such as retired colonial governors were employed, it was felt that a military background and an ability to make decisions on personal initiative was more important than any technical knowledge. Messages were frequently delayed for two weeks or more.

The initial draconian reaction was followed by a process of rationalisation. In October 1914 censors were transferred from Valentia and BalIinskelIigs to the Western Union Offices in London. It was then the duty of Post Office staff at the stations to ensure that all messages were sent via the censors prior to transmission. A censor was maintained at Waterville to deal with the company’s traffic between France and America.

The use of codes in ordinary telegrams was prohibited at the start of the war and this caused a dramatic reduction in the volume of commercial traffic. Banks, financiers and even small companies had always used their own codes. They inhibited the possibility of commercial espionage and they allowed messages to be compressed, thus saving costs. Over a period of time, the rules were relaxed to allow specific code books to be used and decoding clerks were employed in the censorship offices. It would seem that commercial concerns were prepared to tolerate delay rather than sacrifice the confidentiality of their telegrams.

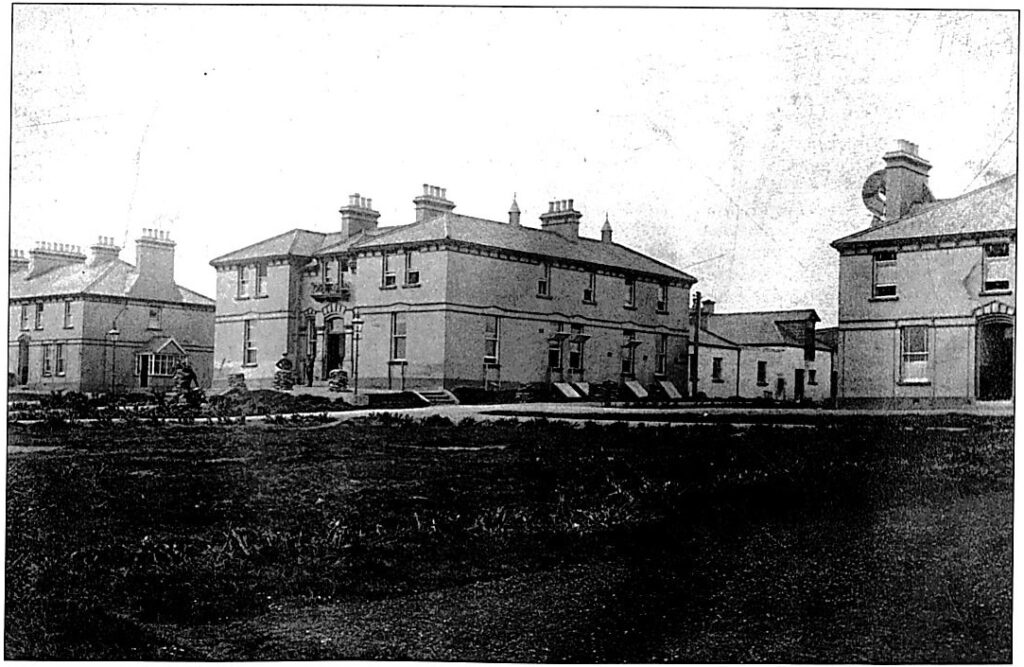

The war changed the way of life for the cable station staff and their families. Each station was now surrounded by barbed wire and kept under military guard. Admission was by pass only and at Valentia the guarded area included many of the staff houses. Even children on their way from school had to show their passes.

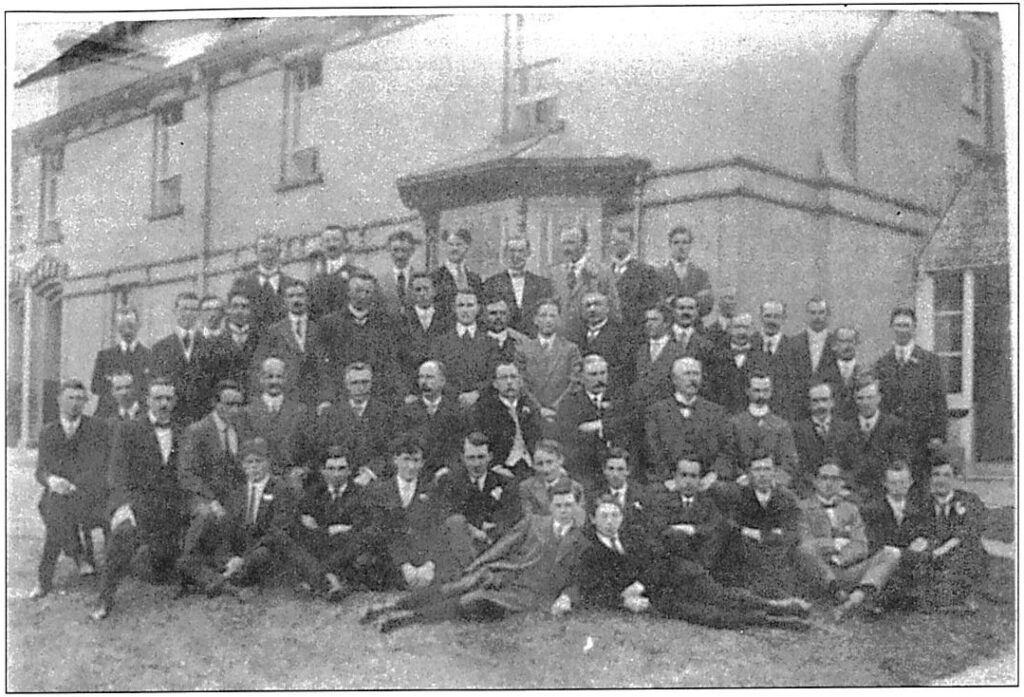

Following the removal of censors to London, there was a large Post Office technical staff at the stations. This was later increased for security reasons so that towards the end of the war there were eleven at Valentia, three at Ballinskelligs and six at Waterville. Nevertheless in spite of their official title and function, the rest of the station staff at Valentia always referred to them as ‘censors’ and although there were fairly cordial relations, both groups maintained their distance.

The other way in which the war impinged on staff at the cable stations was the sheer volume of work that had to be handled. A large volume of traffic required a large staff; indeed towards the end of the war there were 200 people working at the Valentia station. Staff had to work long hours. Twelve hour shifts (6am-6pm and 6pm-6am) were the norm. There was much relief amongst the Valentia staff when in 1917 the fastest cable (in terms of words per minute) went out of service. As the other three were being worked to full capacity, the load per operator was forcibly reduced.

The 1916 Easter Rising

The news of the 1916 Easter Rising was first publicised abroad in America and was largely due to the efforts of certain staff at the Valentia station. Precise details have until recently been classified (document DEFEI 350 in the Public Record Office at Kew, London). ‘

During the early stages of the war, the general spirit of the staff at the Irish cable stations (of which the great bulk were Irish at Valentia and Ballinskelligs and about half at Waterville) were sympathetic to the Allied cause. However some months before the 1916 Easter Rising, it was revealed that a large number of operators at Valentia were Sinn Fein supporters, among them members of the Ring family who formed an important element in the life of the station and included a number who were senior supervising officers.

Some days before the Rising operator Eugene Ring sent an irregular message to Heart’s Content, Newfoundland. It was detected by the Post Office checker and reported to the superintendent. The message did not arouse suspicions as it merely asked the operator at the other end if he wished to buy a bicycle. (It is obvious that this was a trial message intended to test how tight the security system really was. The fact that it was detected confirmed to them that it would be impossible to use the cable directly for the transmission of their more important message.)

Shortly before the Rising, Tim Ring, Eugene’s brother, using an assumed name, sent a message to an address in New York from Valentia Post Office. Popular reports say it was dispatched on the instructions of Austin Stack from Fermoy Post Office. The message – Tom successfully operated on today – was passed as an ordinary private message by the censors in London.

With the publication of the news in New York, it proved impossible for the authorities to hush the matter up and America, not yet in the war, was able to focus full attention on the Irish question. The New York address of the recipient of this telegram ‘was subsequently discovered to be the offices of the Irish Extremist Movement’. It had been sent to the housekeeper in the home of John Devoy.

The Ring brothers were arrested on 15 August 1916 and held under the Defence of the Realm Act. Since Eugene Ring had contravened company regulations (on the transmission of private messages), he was dismissed, but Western Union were unwilling to dismiss Tim who had not broken any company rules. The military wanted all cable staff with republican sympathies to be replaced by operators in the service of the government. Western Union would only acquiesce to these demands if the Post Office or Army Signals Corps were able to make up the loss in manpower. As neither could provide the necessary staff of experienced operators, things remained as they were. There was some concession to pressure from the authorities. Some Irish operators were transferred to the Western Union cable station at Sennen near Penzance. This caused a flurry of official activity. Security was strengthened and three additional Post Office operators were drafted in as scrutineers. Company records indicate that Tim Ring was released from prison on 1 May 1917 and applied to be reinstated. He was appointed to the Accounts Department in the London office where he remained until 1 January 1920.

The aftermath

Despite the end of the first world war, the volume of traffic remained very high as the Allies argued amongst themselves over the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles. However, the Irish stations were living on borrowed time. Technical developments meant that telex on cables (automatic transmission from a keyboard rather than a manually keyed version of Morse code) became feasible and after about 1924 there were no more than about twenty staff at Valentia. Redundant operators dispersed throughout the world, many finding employment in the cable networks which were rapidly expanding elsewhere.

Messages were no longer censored before transmission but this did not mean an end to telegraph interception. Under the conditions of the landing licenses, the cable companies were required to hand over copies of each day’s traffic to the Post Office. This implies that all Irish international cablegrams were subject to scrutiny. The Irish component of total traffic through Valentia and Waterville was so small that it was ‘easier’ to queue it in at the terminus in London. Thus any message arriving at these stations from within the State was first rerouted to London where it joined the bulk of west-bound traffic. Despite some embarrassing questions concerning British scrutiny of American traffic at a US Congressional hearing in the 1930s, this remained the practice for the cable companies until the mid-1960s, when disclosure by Chapman Pincher led to the D-Notice scandal which rocked the government of Harold Wilson.

Conclusion

The Irish stations were of vital strategic significance during this period. The British government, conscious of the mistake of not having its own cable, managed to buy the Ballinskelligs operation from Anglo/Western Union in 1919, but following the disruption of the Civil War in 1922, they had the cable diverted to Penzance and the station was closed. Valentia and Waterville remained in operation as repeater stations until the mid-1960s when advances in telephone cables rendered the network of telegraph cables obsolete.

Donard de Cogan is a senior lecturer in electronics in the School of Information Systems at the University of East Anglia at Norwich. Further reading: D. Hendrick, The Invisible Weapon (Oxford 1992).

Further Reading:

D. Hendrick, The Invisible Weapon (Oxford 1992)