The materials of diplomacy between England and Gaelic Ireland in the later Middle Ages.

By Elizabeth Biggs

From 19 October 1394 until 1 May 1395, Richard II of England fought, negotiated and feasted his way from Waterford to Kilkenny, Dublin and Dundalk and back again. He was the first English king to visit the island in person for almost two centuries. The high point of his stay was the negotiation and performance of over 80 submissions of the Irish kings and their major nobles, recorded in around 60 written documents. All of these submissions involved the Irish kings swearing to be Richard’s ‘true liege man’ and to abide by the king’s peace. While historians have pointed out the ways in which this peace was broken even before the English king’s ship, La Trinitie, left Waterford harbour, they have also debated whether the agreements had any lasting value. Certainly, Richard and his officials thought that they were important, because the English treasurer ordered the documents to be copied for safe keeping and then deposited in the treasury of receipt in Westminster, where other treaties and high-value documents such as Domesday Book were stored. Additional copies were kept in Dublin Castle, in the Bermingham Tower, for working reference within the Irish context. Each individual Irish king would also have a copy of his own agreement. Similarly, at other times in the later Middle Ages Irish kings came to agreements with the English government in Dublin and also received copies of their accords. The surviving copies suggest the importance and ceremonial nature of these events, marking moments of negotiated peace amidst longer-standing, often violent conflict.

OATHS OF LOYALTY, SUBMISSION AND SUPPORT

The records are diplomatic documents recording events on a particular day and at a specific location. Some submissions happened in large, outdoor and public places, such as a field outside the town of Carlow, with a large public audience. Others were held in smaller rooms in Richard II’s lodgings, whether in Dublin, Dundalk, Kilkenny or Drogheda. In all cases, the submissions took place in front of witnesses who could later be asked to swear that they had taken place if there was any question. They were staged with great ceremony, and it could have taken a month or more to set up a meeting. Brian Ó Briain of Thomond (Co. Clare) wrote to Richard on 4 February 1395 but only met him in early March in Dublin. The Irish kings removed their hats, belts and knives before kneeling at Richard’s feet to take a pre-written oath of loyalty, submission and support. They swore that they would come to the Irish parliament, would aid the lieutenant—the chief governor in the king’s usual absence—against rebels, and more. In return, Richard would provide political support and intervene to counter the ambitions of the English magnates. Interpreters—sometimes priests such as Edmund Vale, the master of the Knights Hospitaller in Ireland, or major magnates such as James Butler, third earl of Ormond—translated the text of the oaths and agreements from the Irish used by the submitting kings into English for Richard and his entourage. Once the Irish kings and nobles had sworn on the Gospels to be the king’s liege men and to uphold the agreements, they were received into his service by being given the kiss of peace.

When the public ceremony was over, the text recording the submission was written down and some form of legal authentication issued. In the submissions to Richard from 1394/5, these took the form of notarial subscriptions and marks. A notary public wrote an attestation on each copy of the document that he had witnessed the event, that it was a true representation of what had happened and that it could be relied on later. He then drew his own distinctive mark, like one that belonged to Thomas Sparkford (p. 18), a priest in the household of Richard II who came to Ireland with the king in 1394–5. We find him receiving his wages and robes in the accounts for the expedition. Notaries were mostly used in ecclesiastical contexts, so Richard II’s use of notarised agreements perhaps owed something to the advice, local knowledge and influence of the archbishop of Armagh, John Colton. It may also suggest that both the Irish kings and Richard II wanted to invoke the legal power of the Church, the transnational authority they both acknowledged. If the agreements and the peace were broken, the Irish kings in theory would pay substantial sums of money to the papal courts in Rome, although we have no record of these penalties being enforced. Even as early as the summer of 1395 war was brewing in Leinster. Richard would return to Ireland in 1399, after the death of Roger Mortimer, earl of Ulster, in battle the previous year, to try again to enforce his peace.

‘ENGLISH REBELS’ AND ‘IRISH ENEMIES’

Among the submissions are those of relatively few Englishmen, about whom we have little information other than that they had ‘rebelled’ and were outside of the king’s peace. While they too had to swear allegiance, they were not asked to pay penalties. We also have a lovely example at the very end of Richard’s stay in Ireland when he was already aboard his ship in Waterford harbour, and Toirdelbach Ó Conchobhair Donn unexpectedly arrived with the English rebels William de Burgh and Walter Bermingham. Both men were from Anglo-Irish families with close ties to Irish kings and were major leaders in the west of Ireland. Ó Conchobhair Donn had already submitted, but this proof of political alliance called for a reward. Richard knighted all three men and gave them golden cups. Richard thus was treating the Irish kings similarly but not identically to how he treated the English in Ireland. The phrases used, however, in these agreements and in Richard’s own letter about his experiences in Ireland were usually ‘English rebels’ and ‘Irish enemies’, drawing a clear distinction between ethnicities which did not reflect the full range of cultural backgrounds present in Ireland.

Nevertheless, that does not mean that the Richard II agreements were merely a brief moment of constitutional experimentation, whereby Irish kings might have been transformed into English nobles, summoned to parliament in Dublin and assimilated into colonial government. Later fifteenth-century agreements were not quite so all-encompassing. They are sporadic agreements with individual kings rather than with the whole constellation of powerful individuals across the island. They also tend to be much more specific and keyed into particular cross-community disagreements, such as the agreements made about ‘the detestable custom known as “black rent”’ in the 1440s between Lord Lieutenant John Talbot, earl of Shrewsbury, and various Irish kings (p. 20). There are also, however, similarities and resonances with the earlier submissions. The fifteenth-century ones too have clauses about the Irish lord being the king’s faithful liege man and supporting the English government in Ireland, including a fiction that the relevant lord had ‘always been the [English] king’s true liege man’. They also refer back often to the agreements of 1394–5, ‘if they may be found’. They could be found if needed. We know that as late as the early seventeenth century there were still copies of the 1395 submissions in the records of the Irish exchequer in Dublin Castle, from where they were cited in a legal case.

We do not actually know how many of this type of agreement were made in the later Middle Ages. The surviving examples come to us by chance and accident. Some originals survive in the UK National Archives, where they were deposited among the other diplomatic documents as records of treaties made on the English king’s behalf. They cluster around particular points of conflict and seem aimed at regional pacification rather than full assimilation. Clearly, however, the copies in England are not the whole collection that once existed. One 1449 agreement between Richard, duke of York, and Muirchertach Buidhe Ó Néill involved the archbishop of Armagh, John Mey, who had it copied into his register, which survives in Belfast at the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. Several other agreements are only known because they were taken or copied by antiquarians in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in both England and Ireland. Because of the surviving originals, we can see how these documents were authenticated and handed out, how they might later be used and why they were kept.

INDENTURES AND SEALS

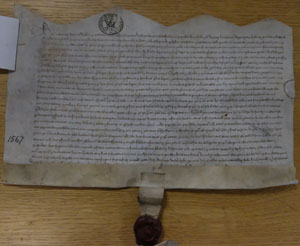

The first exciting thing about the later agreements is that they (sometimes) bear the original seal of the Irish lord making the agreement—rare physical and material manifestations of identity and membership of western European chivalric culture. Seals were personal and heraldic signifiers used to mark acceptance or authorisation of a legal agreement. The later medieval agreements after Richard II’s reign did not use notarial marks but instead were indentures (e.g. p. 20). These are a type of legal document authenticated by the individuals involved and by the legal form and format of the document itself. The agreement would be copied twice onto the same piece of parchment, each written so that the top of the text was in the middle. Once the agreement was finalised, the copies were cut apart with a wavy or zigzag line and impressions of seals in coloured wax would be added at the bottom of each copy, producing the distinctive look of an indenture. The copy with the seal of the English lieutenant would be given to the Irish lord, and the English government would retain the copy with the Irish lord’s seal. If there was any doubt about their validity, the two copies could be brought together to see whether they matched along the jagged edge, and the seals could be checked. The formula used in the documents is usually some variant of ‘in witness of these things, this named person has placed their seal’.

Not every Irish lord had a seal. In 1445 Cahir Ó Diomusaigh came to an agreement with John Talbot, earl of Shrewsbury, who was then the king’s lieutenant in Ireland. Because he did not have his own seal, he borrowed the seal of the prior of Conall Abbey, who was one of the witnesses. This was noted in the text of the agreement because otherwise the seal would not reflect Cahir’s own actions but those of the prior. The images on seals, when they were personal seals, can also be suggestive of how individuals wanted to present themselves in an English legal context. Other Irish lords seem to have had seals that they used when dealing with English officials, such as the seal of Donnchadh Ó Broin in 1425 (p. 21). Here he gave his name in Latin as ‘Donatus Obryn capitaneus [nacionis sue]’; capitaneus nacione is the English term often used for Irish lords in this type of document and can be translated as ‘chief of his kindred’. The English did not usually grant Irish lords the Latin titles of rex (king) or princeps (prince) that they would have used among their Irish [English?] subjects, so Donnchadh is presenting himself in a context that the English would understand.

The documents were kept because they marked points of agreement and, amid high expectations of support for the English government, they often conveyed rights that Irish lords valued, such as the grant of rents or manors in contested territory. They could also be used for improving a lord’s position within Irish political life. Eochaidh Mathghamhna, for example, received the manor of Fernwy in County Louth (modern Farney, Co. Monaghan), worth £10 annually in English money in 1402, when he submitted to Thomas of Lancaster, son of King Henry IV and his lieutenant in Ireland. He was not the lord of Uriel, who was instead Ardghal Mac Mathghamhna. Eochaidh’s ambitions became a threat and he was imprisoned by Ardghal’s son, Brian. The grant of Farney, and the agreements that he might get aid from the English against Ardghal and Brian, would have been good reasons for him to negotiate with Thomas of Lancaster. Over twenty years later, in 1425, amidst conflict within the Ui Néill of Ulster, Brian Mac Mathghamhna was part of negotiations that led to the submissions of Eóghan Ó Néill and Donnchadh Ó Briain, as well as those of himself and his brothers, Ruairi and Mahon. In return, he received English agreement to his right to lands of other Irish nobles in Ulster. Eóghan similarly traded English support for his status within the Ui Néill as lord of Tír Eóghain for acknowledging that he was the vassal of the English earl of Ulster. English ability to enforce the vassalage, however, was very limited.

Our collection of agreements between Irish lords and English rulers is a small fragment of what would once have been a much larger body of materials testifying to the regular contact and negotiation on the borders between the English and Gaelic Ireland. The ceremonies of submission played out before their audiences, and then fixed by writing them down and archiving copies, were important occasions that could be referenced in the future, but they also reflected political aspirations that might quickly change and were hard to enforce. In the longer context of the fifteenth century, Richard II’s agreements look more all-encompassing but also more fragile.

Translations of the agreements between Irish lords and English rulers are now available on the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland website (https://virtualtreasury.ie/curated-collections/irish-kings-and-english-rulers).

Elizabeth Biggs is a postdoctoral research fellow in medieval history working on the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland project at Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

P. Crooks (ed.), Government, war and society in medieval Ireland (Dublin, 2008).

E. Curtis, Richard II in Ireland, 1394–5 (Oxford, 1927).

S. Kinrons, ‘In the footsteps of a king’, History Ireland 24 (1) (2016), 14–17.

D. McGettigan, Richard II and the Irish kings (Dublin, 2016).