by Ian McCabe

Before President John Fitzgerald Kennedy visited Ireland, there was considerable behind the scenes diplomatic and security manoeuvring. Six months before the visit, Secretary of State Dean Rusk paid a flying visit and met members of the government. During his six hour stay, he lunched with the Taoiseach, Sean Lemass, and Minister for External Affairs, Frank Aiken. They discussed Cuba, the Congo, the EEC and ‘limited hopes’ for a nuclear disarmament conference. The US Ambassador to Ireland, Mathew McCloskey, was impressed by the red carpet treatment accorded to Rusk, informing Lemass that ‘it set a standard for all time’. A couple of weeks later, during his Christmas holidays McCloskey met Kennedy who told him he was ‘anxious to visit Ireland’ and spoke about an earlier visit to his Irish relations in Wexford.

No red carpet

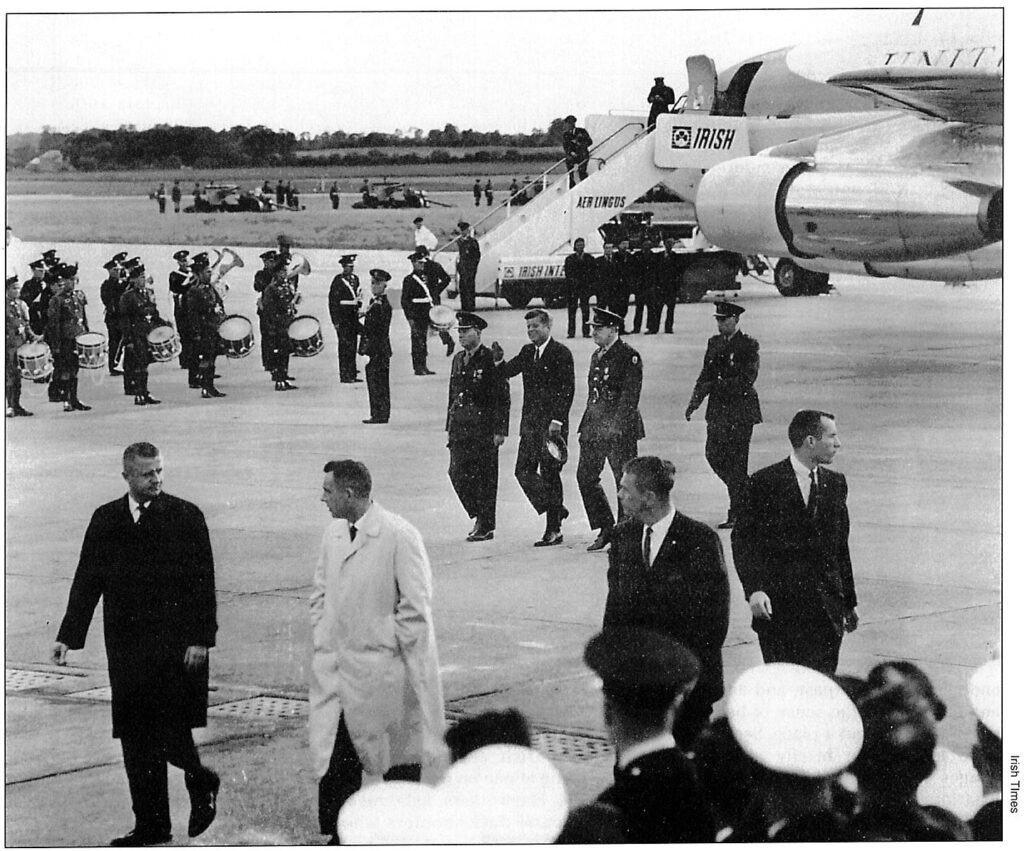

At three minutes past eight on the evening of 26 June 1963, President John Fitzgerald Kennedy arrived at Dublin Airport. A few days before, the Office of Public Works had decided President Kennedy arriving at Dublin airport. The OPW decided against a red carpet in case of rain. not to lay a carpet on the airport tarmac fearing it might rain and ruin the carpet ‘at a total cost of £250’. The fifty-strong reception party of state dignitaries contained only one woman, the president’s sister, Jean Kennedy-Smith, now US Ambassador to Ireland.

Kennedy’s charismatic personality, his commanding presence, ability to combine humour and seriousness, statesmanship with the common touch, made him a perfect performer for television. Accordingly, the visit was stage-managed by a public relations team who arrived ahead of the Presidential party. They ‘strongly expressed’ their wishes to the Department of External Affairs that the airport ceremonies should take place in the open and that press, radio and television representatives should be accommodated close by in a special enclosure on the tarmac. In contrast, the Irish Embassy in Washington warned External Affairs . about American journalists: ‘stern measures may be necessary on all public occasions to keep them in order. They are accustomed to taking more liberties in the US than their brethren in Ireland would dream of doing and it is to be feared that they will behave in the same fashion when they get to Ireland.’ In accordance with his policy of maximising photo opportunities, Kennedy travelled with President de Valera in an open car to Áras an Uachtaráin.

A month before, representatives of the gardaí and the military were arguing over whether troops should line the route. The military maintained that lining the streets with troops was an important part of the army’s ceremonial duties and were worried that if absent the public might get the impression that their ceremonial activities were being curtailed. The gardaí were ‘strongly opposed’ to any form of street lining by troops because it ‘rendered control of crowds by the police almost impossible.’ The military were prepared to compromise and suggested that they line the route either from the Parnell Monument to O’Connell Bridge or from the Central Terminal Building at the airport to the entrance on Collinstown Road. Diplomats at Iveagh House ascertained that the gardaí’s objection to lining a portion of the route at Dublin airport would not be ‘at all so strong’ as their objection to the O’Connell Street route.

Diplomatic strain

From the files it is evident that there was a certain amount of jockeying for position among US and Irish officials. This caused some diplomatic strain between the departments involved. The Central Intelligence Agency assumed that the US secret service would control security arrangements. Indeed, Kennedy brought his own personal armed bodyguards. Reputedly one of the advance team of secret service men drew his gun during a fracas in the bar of the Intercontinental Hotel. Such was the goodwill towards Kennedy’s entourage that the press did not report the incident.

The Department of Posts and Telegraphs were wary of supplying US security officials with personal information about their staff. They informed External Affairs that they were not prepared to give US officials more than a list of names, addresses and telephone numbers of engineering staff entering the security areas of Dublin airport and recommended that ‘we should not deal directly with the Americans on this matter.’

On the first morning of his visit Kennedy met the Taoiseach, Sean Lemass, for diplomatic discussions at the US Embassy residence. For the Irish government, this was the highlight of the visit. It represented public acknowledgement that Ireland had been accepted back into the western fold despite the ‘rejection’ of NATO and military neutrality.

Lemass an ‘inveterate gambler’

The Central Intelligence Agency provided Kennedy with a detailed profile of the political and personal lives of members of · the cabinet, including the allegation that Lemass was an ‘inveterate gambler and as a result has at times been involved in serious financial difficulties.’

Kennedy had been briefed by the State department to press for the removal of the compulsory stop-over at Shannon. However, he had also been advised to thank the Irish government for their assistance during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis in searching Eastern bloc aircraft at Shannon en route to Cuba and to press for the continuation of these searches. Although the transcript of the talks do not refer to the Shannon talks nor reveal the outcome, it might be reasonable to suggest that a quid pro quo arrangement was agreed ‘behind closed doors’, symbolised by Kennedy’s eventual departure from Shannon. Additionally, Kennedy was reminded to thank Ireland for her contribution to ‘world peace’. He drew attention to Ireland’s intermediary role between the West and the Third World, referring specifically to the Irish-sponsored resolution which quelled hostilities between Pakistan and India over the Kashmir border dispute. In particular he expressed thanks for Ireland’s peace-keeping role — a reminder of the 1961 Congo massacre and the loss of twenty three men during that peace-keeping operation.

Referring to De Gaulle’s dislike of the US monopolising the West’s nuclear deterrent, Kennedy explained that ‘if danger of nuclear war emerged there would not be time for a committee meeting to discuss it’. He implied that the Soviet Union accepted US supremacy and was no longer a danger but feared that the Chinese would become a nuclear power and with their ‘enormous population and Stalinist doctrines, they will, by then, be the major problem for the world, which our successors will have to face.

Partition discussed

As though playing cat and mouse, both men waited until they were well into their talks before Kennedy broached the subject of partition asking ‘is any progress being made?’ Kennedy had been briefed to state that the US was unable to take a position on the issue but to add that the EEC would diminish the importance of borders. Lemass did not press him to intervene on partition, saying that ultimately ‘this is a question which must be settled in Ireland, that any form of international pressure would not alter the basic situation’. Referring to the practical difficulties of uniting Ireland, Lemass, building on Kennedy’s reference to the EEC, explained: ‘We had seen in membership of the EEC the solution of certain problems, including our commercial relations with Britain, our participation in European political integration including defence, and the economic consequences of partition.’

This could be interpreted as offering co-operation with the western powers on defence without strict prior conditions on unity. Lemass’s vision of an united Ireland included ‘the retention of the Northern Ireland parliament and government with their present powers’. He told Kennedy that ‘what we wanted from the British government was an indication that they would welcome such agreement in Ireland and that there was no British interest in preventing it’. Lemass hoped that Kennedy would act as a go-between and pass on these remarks in the hope that the gesture would be reciprocated by Britain. Lemass’s approaches were ignored.

CIA expected demonstrations

The CIA expected that there would be demonstrations to highlight partition. However, the only public embarrassment was when the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O’Neill, publicly invited Kennedy to visit a NATO base in Derry to see the contribution Northern Ireland was making to NATO. Lemass learnt that the UK Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, was angry at O’Neill’s stunt. Less publicly, a splinter group of nationalist MPs in Northern Ireland failed in their attempts to pressurise the Department of External Affairs to arrange a meeting with Kennedy to discuss partition. External Affairs noted that Eddie McAteer ‘is very unhappy about this request and wishes to disassociate himself from it.’

Ten shillings charge

Following his meeting with Lemass, and accompanied by Frank Aiken, Kennedy flew by US helicopter to New Ross where he was greeted by the colourful Chairman of the Urban District Council, Andrew Minihan. The protocol division of External Affairs had earlier made known its displeasure over the proposal to build a platform in New Ross to accommodate 2,000 people, with an admittance charge of ten shillings.

From New Ross, Kennedy travelled by motorcade to the ancestral home of his great grandfather in Dunganstown. Files relating to security on the visit refer to the gardai’s heightened concern because ‘of a serious breakdown in the policing’ during former president Dwight Eisenhower’s visit to Wexford the previous August. Kennedy’s second cousin once removed, Mary Ryan, had assured gardai that only twenty people would be invited to the house including the parish priest and curate. Despite the crushing crowds, pictures of Kennedy having a cosy chat over tea with his cousin Mary were relayed throughout the world. Reports from Irish embassies record that photographs of the meeting touched the hearts not just of emigrants in America but of people throughout the world.

From Dunganstown he flew to Wexford and landed in the town park. The Town Clerk had informed the gardai that he was ‘opposed to the admission’ of members of the public to the park during the landing. From the park Kennedy travelled by motorcade to Crescent Quay and solemnly laid a wreath at the statue of John Barry, ‘the father of the American Navy’. Next, he went to Redmond Place where the Mayor, Thomas Byrne, bestowed the freedom of Wexford town upon him.

Garden party turned into ‘rugby scrummage’

Back in Dublin that e'(ening he attended a Presidential garden party in Aras an Uachtarain. Much to the embarrassment of External Affairs, overseas newspapers derided the rain-swept evening: ‘It was part rugby scrummage and part adoring struggle for the glory of a presidential handshake. It was everybody for himself. No nonsense about waiting to be called forward for an introduction.’

Later that evening Kennedy attended a State Dinner at Iveagh House. The Civil Service Dining Club was responsible for the function. Special Branch checked all staff in advance and on the night, each was personally identified. Staff from the dining club normally gained access to Iveagh House through an interconnecting basement door. Shortly before the beginning of the function, it was found to be locked. The Dining Club chairman later complained to External Affairs that it was only with the assistance of the Special Branch that they managed eventually to get the doors unlocked with only half an hour to go before the commencement of the reception; he wrote that ‘certain candelabras, flowers and other table decoration which we had prepared beforehand could not be set up.’ The dinner for eighty one people cost £1,575 13s 2d.

On the third day of his visit Kennedy was awarded the freedom of Cork city by the Lord Mayor, Sean Casey. Members of the Fitzgeralds of Cork complained to him that not enough recognition was given to his grandfather, a Fitzgerald, who was mayor of Boston. Kennedy quipped that his vote-catching grandfather ‘used to tell everybody he was from Limerick and Donegal and Galway or wherever.’

That afternoon Kennedy addressed a joint session of the Oireachtas. Permission to televise the proceedings had been granted to RTE Director General, Kevin McCourt. He supervised a survey of Leinster House assuring the Ceann Comhairle, Patrick Hogan, that the cameras would not interrupt the proceedings. Kennedy declared prophetically in the course of the speech: ‘Those who suffer beyond that wall I saw in Berlin must not despair of their future. Let them remember the constancy, faith, endurance, and final success of the Irish .. .’

Following his visit to the Oireachtas, he went to Dublin Castle where the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Sean Moore, awarded him the freedom of the city. Later that day he received honorary doctorates at both the National University and Trinity College. Diplomatically he claimed that he now felt part of both: when they were opponents in sport he would ‘cheer for Trinity and pray for National’. On the last day of his visit, he was greeted in Galway by crowds which included three hundred schoolchildren dressed in green, white, and orange forming a representation of the national flag. In Eyre Square the Mayor, Patrick Ryan, awarded him the freedom of the city. He departed from Salthill for Limerick by helicopter to the strains of ‘Galway Bay’.

Publicity ‘worth millions’

Originally, Limerick was not on his itinerary. However, it was included following questions in the Dail by Stephen Coughlin and a personal letter from Thomas O’Donnell to Frank Aiken which pointed out ‘the President’s grandfather Mr Fitzgerald visited Limerick in 1938 and met relatives in the Bruff area’. The mayor, Mrs Frances Condell, welcomed Kennedy to Limerick and at City Hall conferred the freedom of the city upon him. By all accounts she gave the most eloquent welcoming speech of the tour. His final visit in Ireland was Shapnon. Welcoming him, the chairman of Clare County Council, Sean Brady described him as ‘a prince of peace’.

The Irish Embassy in Washington reckoned that the publicity was worth ‘millions’. At that time it was customary to give first place in the news to any major story about the President. Accordingly US newspapers, several thousand radio stations and the three major TV networks, NBC, CBS and ABC allowed a total audience of seventy million to share in Kennedy’s visit home.

National morale uplifted

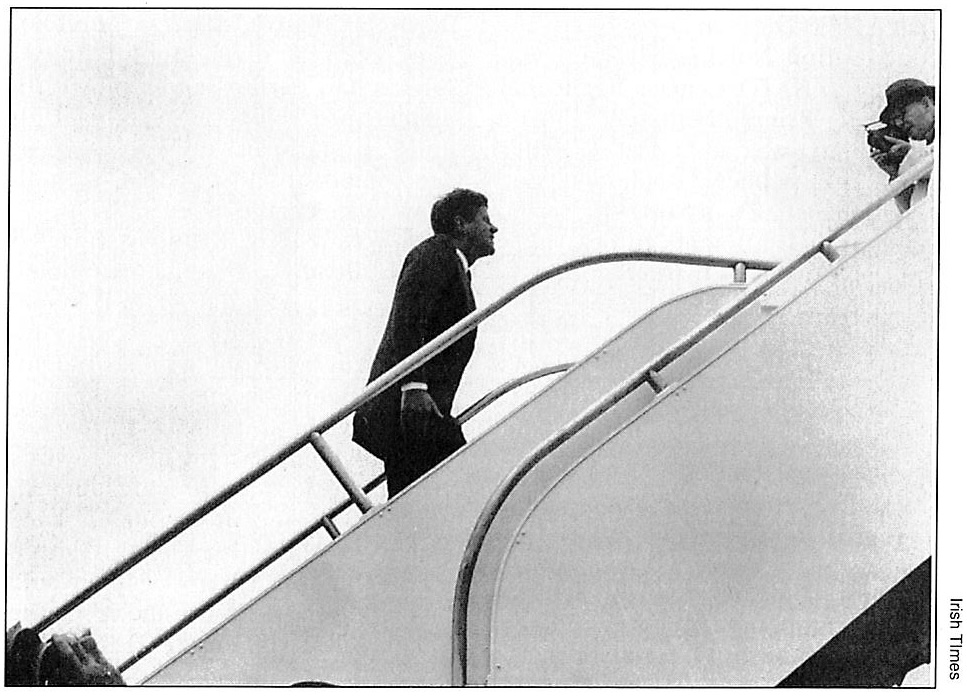

The triumphant return of the great grandson of an emigrant as the thirty- fifth President of the US uplifted national morale — as though the Irish had been waiting for this archetypal ‘return’ to confirm that the wounds caused to the national psyche by the famine and emigration had been healed. Kennedy spoke often of returning — ‘I can imagine nothing more pleasant than day after day to drive through the streets of Dublin and wave — I may come back to do it.’ But it was not to be. His assassination five months later left Irish people numbed, as though a close relative had been lost.

Ian McCabe is author of a diplomatic history of Ireland 1948-49.