By Fiona Brennan

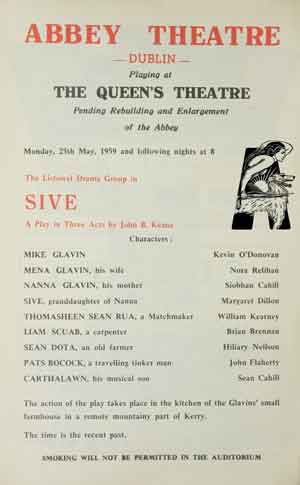

The dramatic tragedy Sive, written by the Kerry playwright John B. Keane, enjoys iconic status within the annals of Irish theatre history. Following its initial rejection by the Abbey Theatre in 1958, its acclaimed production by the amateur Listowel Drama Group the following year is legendary. Sixty-five years later, the play remains a popular choice among drama groups countrywide. Its most recent revivals were by the Abbey (2014) and Druid (2018) theatre companies, and earlier this year its production at the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin enjoyed a seven-week run, which is, perhaps, a testament to the unflinching fascination that this tale still holds for the theatre-going public.

Set in Kerry during the 1930s, it tells the story of Sive, an eighteen-year-old illegitimate orphan who lives with her uncle, Mike Glavin, his wife Mena and his mother, Nanna Glavin, on a small holding. Mena is approached by the matchmaker, Thomasheen Seán Rua, to arrange a match for Sive with a prosperous farmer, Seán Dota. This lecherous old man, who is almost 70 years old and described as a ‘hardy thief with the mad mind’ for the young girl, has promised the Glavins 200 sovereigns should Mike consent to the match.

When two tinkers, Pats Bocock and his son Cartalawn, call on Nanna the tension in the house heightens. In both verse and rhyme, the men share their dark forebodings at the impending marriage. Indeed, tragedy does strike when, the night before her wedding, Sive makes her escape across the bog, where she falters and drowns. In the play’s final moments, her sweetheart, Liam Scuab, enters the kitchen carrying her body across the threshold. It is one of the most enduring images in twentieth-century Irish drama. As Sive’s body is laid on the table, Scuab castigates Mena, accusing her of murder. At the same time, both the matchmaker and Seán Dota sneak out the door as stealthily as possible. Keane later confirmed that he was ‘writing about the thirties [in an Ireland where] … times were never harder since the Great Famine’. The play is an ominous reminder of an era when an innate Catholic moral order held Irish society to ransom and where appearance was everything. The play’s themes exposed the contemptible air of superiority of those who identified illegitimate children like Sive—and her unmarried mother before her—as morally reprehensible.

Keane, a publican in Listowel town, once recounted that a customer asked him where he might buy a very cheap ring. Keane duly obliged with the information and, weeks later, was sickened at meeting the ugly old man with his seventeen-year-old bride trailing behind him. At the time of the dissolution of the Cumann na nGaedhael government in 1932, the Free State was in the throes of the Great Depression, which caused a depletion in trade and spiralling unemployment rates. The great majority of the population was living in the countryside, where most agricultural holdings were very small. There was a pattern of late marriages as well as very high birth rates within marriage. The advancement of protectionist policies by the new Fianna Fáil government and the continuing economic war with Britain suppressed trade and prolonged mass emigration.

The Catholic Church’s dominance of Irish society and its control of people’s moral and social lives was unforgiving. Clerical condemnation of promiscuous behaviour and the evils of sexual immorality reached near-hysteria. Subsequently, the Church’s so-called ‘Lenten ban’ on attendances at cinema and dancehalls intensified people’s search for alternative social entertainments. Thus dancehalls began to reverberate to the sounds of amateur dramatic activities. There was a phenomenal increase in dramatic expression and countless new groups were formed. Many of these groups became inclined towards developing productions on a more ambitious footing and the 1940s became synonymous with the advent of drama festivals, which nurtured a highly competitive spirit amongst participating groups. Several groups produced contemporaneous Abbey plays by T.C. Murray and P.V. Carroll, among others, which encompassed hard-hitting societal, cultural and religious themes.

The significance of the festivals’ ‘New Writing’ award proved fortuitous for aspiring playwrights like Keane. He had never disguised his disgust at the Abbey’s initial rejection of Sive and, following its all-Ireland winning success in 1959, an Abbey invitation was issued to the Listowel group to perform the play there. This brought the playwright immense satisfaction. At that time, Micheál Ó hAodha, the head of RTÉ radio drama, commended the festivals’ promotion of new writing, without which, he claimed, professional theatre could not have survived. It was fortuitous for Keane that, since its founding in 1944, the Listowel drama group had developed into an impressively talented outfit. Its co-founder, the Abbey playwright Bryan MacMahon, had his first play, The Bugle in the Blood, produced at the Abbey in 1948. Two more group members, Eamon Kelly—who appeared in all three Abbey productions of Sive between 1985 and 1993—and his wife Maura, joined the Raidío Éireann players in 1952.

When Brendan Carroll, producer with the Listowel drama group, read the script, he identified its raw potential as well as its necessary reworking, to which Keane agreed. While Carroll believed in the play’s potential to win all-Ireland glory, he was concerned that it would be ‘too strong for the more sensitive in the audience’. There had been no need to worry and, following its première at the Listowel Ballroom in February 1959, word spread like wildfire regarding this ‘must-see’ play. Similarly, when the group embarked on the competitive circuit, travelling to festivals in counties Clare, Kerry, Cork and Limerick, the excitement was at fever pitch. Black market tickets went on sale at the Kerry festival in Killarney, while at the Fr Matthew Hall in Limerick City a Garda presence was deemed necessary by the organisers to deal with the raucous crowd of people who had failed to gain entry to the performance.

With hindsight, the success of Sive is a credit to the innovative spirit within the amateur dramatic movement and to all those who believed in the theatrical majesty of Keane’s dark tale from North Kerry, which exposed Irish theatre to the erstwhile inexpressible dark underbelly of Irish society.

Fiona Brennan is co-editor (with Neil Buttimer and Gabriel Doherty) of The art and ideology of Terence McSwiney: caught in the living flame (Cork University Press, 2022).