By John Gleeson

When an eighteen-year-old Kerryman named John Sullivan arrived at a famous French military academy in La Flèche in 1785 to teach English and mathematics, few could have predicted the diverse and colourful life that was to follow. By 1793 Sullivan had sworn an oath of loyalty to the new French constitution and had become a French citizen. He had also acquired a political apprenticeship in the local Jacobin Club.

LA VENDÉE

By 1795 Sullivan had moved closer to the centre of political power in France by joining the French foreign ministry in Paris as the youngest of seven translators working under the watchful eye of the Head of Translation, his uncle and fellow Kerryman Nicholas Madgett. There he translated extracts from the English press, which became a prolific source of political and military intelligence for the French leadership. In 1796 he was part of the intensive linguistic and political collaboration between Nicholas Madgett and Tone. That collaboration was instrumental in persuading the French Directory to decide in June 1796 to launch a large military expedition to Ireland. Tone recorded his interaction with Sullivan in his diary entry for 3 April 1796: ‘After dinner walked with Sullivan for two hours in the Tuileries, talking red hot Irish politics. Sullivan is a good lad and I like him very well.’

WITH HUMBERT

Sullivan would have been well aware that his activities in France were probably known to the British authorities and would have been treated as treasonable were he to set foot in Ireland. The teacher, interpreter, translator, propagandist and intelligence operative was following his own rhetoric onto the battlefield when he returned to Ireland in 1798 with the small French invasion force led by General Humbert. Sullivan came in disguise as a French army officer, ‘Capitaine Laroche’. It nearly cost him his life. The story of his escape from the custody of the British Army after the surrender of French forces is a remarkable episode of his short life.

Why was Sullivan selected to go on that expedition? Humbert’s letter of 19 December 1798 to the Directory after the failed expedition explains that he needed un officier connaissant la langue et les usages du pays [‘an officer who knows the language and the customs of the country’]. There is no direct evidence that Sullivan was an Irish-speaker, though Humbert may have been adverting to the Irish language. Humbert adds in the same letter that Sullivan was appointed as the commander of the Irish volunteers whom he led into battle at Castlebar, and it is difficult to imagine how he could have carried out such a mission without communicating in Irish, which was probably the language of many local volunteers. Linguistic competence in French was, however, to prove crucial to Sullivan’s own survival.

Humbert’s letter of 19 December 1798 to the French Directory contains a eulogy of Sullivan’s performance during the unsuccessful invasion. Humbert recounts that Sullivan was not driven by any personal interest but nevertheless exposed himself to real danger. Humbert had appointed Sullivan to the rank of captain, but the departure from France was so hasty that the formal arrangements had not been put in place to confirm his appointment. According to Humbert, confirmation of Sullivan’s rank of captain would be small recompense for the sacrifices he had made. That rank was never subsequently ratified.

CASTLEBAR

Humbert gives a personal account of Sullivan’s bravery at the battle of Castlebar, which was the first French confrontation with British troops during the expedition. Sullivan’s appointment as the commander of the Irish volunteers meant a promotion in the field to battalion commander. He refused to accept the promotion, declaring himself content with the rank of captain. Richard Hayes also records Sullivan’s bravery in The last invasion of Ireland by referring to the reminiscence of a French general, Fontaine, that Sullivan exhibited ‘the most striking proof of individual valour’. Humbert’s assessment of Sullivan is fulsome: ‘Il a constamment montré l’attachement le plus inviolable pour la République et la haine la plus invétérée pour les oppresseurs de sa première patrie’ [‘He consistently showed the most unbreakable loyalty to the Republic and the most deep-seated hatred of the oppressors of his country of birth’].

Humbert’s observation denotes a form of symbiosis between Sullivan’s support for the French Revolution and the cause of the United Irishmen. Just as France had unchained itself from the fetters of monarchy and feudal privilege, a French invasion of Ireland would free that country from the yoke of English oppression. Sullivan’s active participation in the French military expedition demonstrates that he was concurrently loyal to the French Republic and a committed supporter of the United Irishmen. He also lost no time in trying to convert Irish soldiers who had been captured from the British side, if one is to believe the contemporaneous account of one James Fullam cited in Hayes’s work. This rings true in the light of Sullivan’s experience of proselytising English sailors in Brittany.

BALLINAMUCK

The 1798 Rebellion in Ireland had taken the French authorities by surprise. Much of France’s military strength was invested in Bonaparte’s campaign in Egypt. Signs of a new European coalition against France meant that resources for an Irish invasion were limited. In the event, Humbert recklessly led a contingent consisting of 1,000 untrained Irish volunteers and 900 French soldiers into battle at Ballinamuck, Co. Longford, in September 1798 against some 20,000 troops commanded by Cornwallis.

French officers were permitted to return to France immediately after the surrender to Cornwallis, as was the convention, but not Sullivan. He was detained and questioned on suspicion of being an Irish volunteer. The Freeman’s Journal of 13 September 1798 records that two French officers, believed to belong to the ‘Irish Treason Union’, were taken under British army escort to Dublin Castle. The report adds: ‘One says his name is La Roche and the other Tailon but it is suspected they are Irishmen and their real names Roche and Teeling’.

ESCAPE

Humbert confirms Sullivan’s own version of his escape after defeat at the hands of the British army. It was indeed a miracle that Sullivan escaped, which Humbert attributes to the adoption by Sullivan of the name ‘Laroche’ before his departure for Ireland, so as to assume the identity of a French officer. A number of documents emanating from both General Humbert and the French war ministry refer to him under the style of ‘Sullivan dit Laroche’ [‘Sullivan known as Laroche’] in the immediate aftermath of the Mayo adventure. A letter dated 29 December 1798 from Humbert to the war minister, and written in Sullivan’s unmistakable hand, denominates him as ‘Le Capitaine Sullivan, connu sous le nom de Laroche dans l’expédition d’Irlande’ [‘Captain Sullivan, known by the name of Laroche on the Irish expedition’].

Nevertheless, his escape cannot be attributed simply to the adopted French surname. Two further sources paint a fuller picture. A letter from the French ministry of war to the Directory in late December 1798 states that Sullivan was brought before a court martial after being captured by the British, but he was spared because it was not possible to prove that he had been born in Ireland, though his country of birth was almost certainly the subject of intensive interrogation.

Internal British army correspondence authored by Rupert George, dated 22 November 1798, yields further telling detail. This letter, filed in the National Archives in London, has not previously been brought to light and explains that ‘La Roche, a French officer’, left Dover with General Humbert on 26 October 1798, when they were repatriated to France. In an attempt to explain how Sullivan had been released, the author states:

‘We examined him very particularly previous to his departure and had no reason to doubt the account he gave of himself “that he was born in France of Irish parents”. He certainly spoke the language of a Frenchman and was detained in Ireland some days in custody after General Humbert left that kingdom, but no proofs of his being an Irishman having appeared, he was allowed to join his General at Litchfield.’

The letter strongly suggests that reservations about Sullivan’s nationality resurfaced not long after his departure from Dover to France in October 1798. Why those doubts appeared so soon after his interrogation is unclear. Secret military intelligence passing from Castlereagh to Wickham c. 29 October 1798 suggests that it was Edward Cooke, then British under-secretary in Dublin Castle, who let Sullivan slip through the net: ‘… he [Sullivan] was dismissed by Mr Cooke, with the other officers, having satisfied him that he had been born in France of English parents’.

The Irish who landed with Humbert in County Mayo were court-martialled and executed almost immediately. Local Irish volunteers were slaughtered after the French were defeated. Sullivan was in a situation of extreme peril. He owed his life to a clear command of spoken French, which his interrogators believed to be indistinguishable from that of a native speaker.

John Sullivan’s bilingual competence was beyond dispute and had been noted in an entirely different context earlier in 1798. He had translated a romantic novel, Ranspach or Mysteries of a Castle, from English into French. The reviewer in the Journal des Dames remarked that Sullivan’s knowledge of French was so exceptional that it read like an original work rather than a translation. His escape is all the more remarkable when one considers that he had crossed paths with a British government informer, Michael Burke, who had infiltrated the French forces in Castlebar on 31 August 1798. Sullivan, who was born in Tralee in 1767, had translated himself out of captivity and probable execution. He returned to Paris on 1 November 1798 with General Humbert.

DEATH

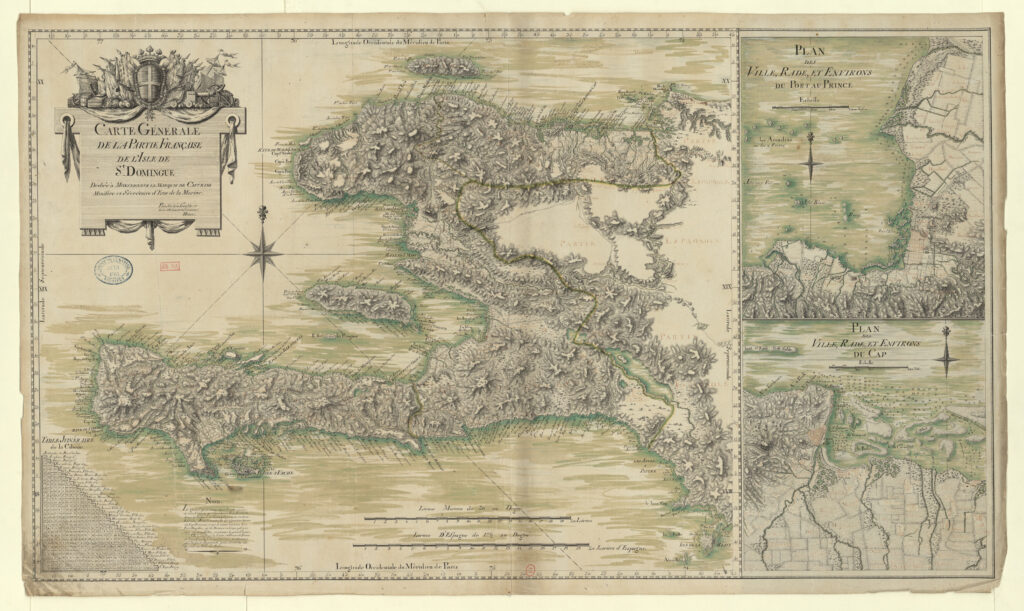

Despite having put his life on the line for the dual objectives of the French Republic and Irish independence, Sullivan subsequently had to survive a series of temporary military commissions in the French army. This was a far cry from the prestigious position of translator in the French foreign ministry. His untimely death from yellow fever in 1802 in a military hospital in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) occurred in the course of a Napoleonic expedition to retake control of the sugar-rich island. It is ironic that Sullivan, the United Irishman who embraced the revolutionary concepts of liberty and equality, should perish on a mission driven by Napoleon’s desire to restore slavery in the French colony.

John Gleeson is a post-doctoral researcher in the Trinity Centre for Literary and Cultural Translation.

Further reading

M. Elliott, Partners in revolution: the United Irishmen and France (Yale, 1982).

H. Gough & D. Dickson (eds), Ireland and the French Revolution (Dublin, 1990).

T.W Moody, R.B. McDowell & C.J. Woods (eds), The writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone, Vol. II. America, France and Bantry Bay, August 1795 to December 1796 (Oxford, 2001).