By William Cumming

Kilmainham Gaol is significant as the site of the executions of the 1916 leaders and of the imprisonment of many of those involved in the major struggles for independence or reform during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But it is often forgotten that the prison was built, and primarily served, as a place of confinement for ‘common criminals’.

In the eighteenth century prisons were places of cruelty and squalor. Kilmainham was to be different. Inspired by the ideas of the Enlightenment, the new prison was to be a modern facility where, through a regime of separation, hygiene and work, prisoners would be reformed to be ‘safely’ released back into society.

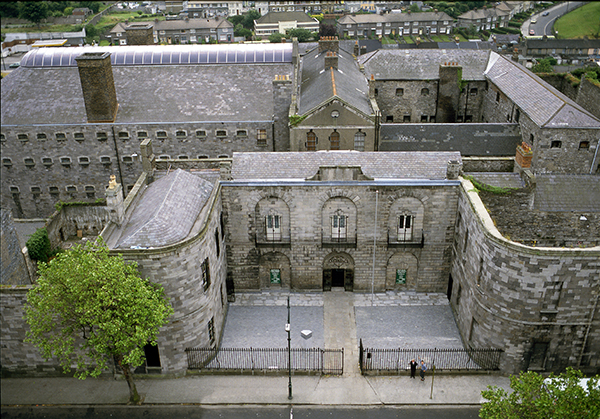

The original complex, opened in 1796 and built to a design by Sir John Trail (c. 1725–1801), had an entrance and administrative block to the north, a spine block running north–south and, to either side, the cells set around two central yards. A series of yards, dedicated to specific activities or types of prisoner, were arranged around the cell blocks. A high limestone wall with bastions to the four corners enclosed the entire complex. The present entrance block, with its heavy rusticated and vermiculated stonework and chained hydra (a mythical and dangerous many-headed serpent) over the door, was part of the original building. The two wings on either side of the entrance, forming the entrance court, are later additions: to the east the governor’s apartments, to the west the stone-breakers’ yard. Public hangings were from a gallows directly above the doorway; the combination of the hydra in chains and the hanged emphasised the control of those threatening society.

Despite the original intentions the prison soon became overcrowded, with cells built for one often holding multiple prisoners. In 1840 a block of 30 cells was added to the west wing, but soon after this was completed there was a major increase in prisoners arising from the Great Famine. The prison registers for the period show a dramatic rise in imprisonment for food-related offences. In times of mass famine a prison diet was preferable to starvation. To discourage such prisoners the prison diet was reduced to a minimum.

The next major attempt to deal with overcrowding involved the demolition of the old east wing and its replacement in 1861 by a new three-storey-over-basement wing to an award-winning design by John McCurdy (c. 1824–85). This is a classic Victorian prison design organised around the principle of central observation and control, allowing prison staff to have, from a central point, a view of every cell door in the block.

The prison finally closed in 1910, only to reopen six years later as a detention centre after the Rising. It continued in use as such to the end of the Civil War. It lay empty and falling into ruin from 1924 to 1960. Photographs from the 1950s show collapsed roofs and trees growing out of the rubble. Various proposals, including demolition, were considered.

The Kilmainham Gaol Restoration Committee, a voluntary body, was established in 1960 with the objective of restoring and reopening the prison for the 50th anniversary of the Rising. Kilmainham was officially reopened in 1966 by President de Valera, its last prisoner. The Committee continued to manage the prison until it was handed over to the state in 1986.

William Cumming is Director of the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Series based on the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage’s ‘building of the month’, www.buildingsofireland.ie.