There is a difference between the Irish battle for the land in the nineteenth century and the battle for the soil. Soil is what land becomes when it is ideologically constructed as a natal source, that element out of which the Irish originate and to which their past generations have returned. It is a political notion stripped, by a strategy of sacralisation, of all economic and commercial reference.

‘Racy of the soil’The epigraph for The Nation, ‘racy of the soil’, indicates that newspaper’s determined drive towards a ‘rediscovery’—really a reconstruction—of authenticity. The struggle for the land and, indeed, the struggle with the land, is contrastingly marked by an inexhaustible series of references to its economic status—property, rent, productivity, upkeep, leases, encumbrances, improvement, impoverishment, ownership, tenant right, landlord right, buying and seIling, state purchase, redistribution, etc .. The distinction is not peculiar to Ireland nor is it confined to versions, sacred and secular, of territory. It has its origins in the counter-revolutionary reaction to the radical redrawing of French territory during the revolution when the traditional boundaries between the old provinces were replaced by divisions based on a mathematical and symmetrical model. Burke fulminated against this rationalisation but so too did French commentators, seeing it not only as an assault on historically sanctioned pieties, but as a characteristically modern reinterpretation of land as merely an administrative or economic category. Stripped of its ancient associations, it entered into the world of the political economists whose new-fangled idiom of measure and price displaced the older idiom of presence and value. Nationalism was the two-faced ideology that could exploit both idioms, although in doing so, it rarely interfused them. It could make the claim to authenticity in terms of the soil and make that in turn part of the concurrent claim to ownership of the land. In Ireland, the relationship between landlord and tenant was particularly fraught; the relationship between the land and its inhabitants was dangerously poised, especially after the agricultural collapse of 1815 and the continuing rise in a population increasingly dependent on one crop—the potato—and even more on one variety of that crop—the lumper. Lalor and DavittThe Famine made the exchange between soil and land a politically charged transaction. Two writers in particular, James Fintan Lalor and Michael Davitt, made the distinction between these terms a central feature of their political programmes. In effect, ownership of the soil was interpreted by them as a national right; ownership of the land was an individual claim. In his pamphlet Some Suggestions For A Final Settlement of the Land Question (1902), Davitt admitted that his ‘plan of Land Nationalisation’ had failed: The plan was either disliked, or misunderstood, or the principle on which it rested—national, as against individual, lordship of the soil—did not appeal to the strong human desire or passion to hold the land as ‘owner’ which is so inherent in Celtic nature. In addition, Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party had deferred to the wishes of the tenant-farmers, ‘the preponderant political force in Ireland’, ignoring the cottiers’ claims: so the country has remained … overwhelmingly for an ‘occupier ownership’ of the land as against the ‘national ownership’ which Fintan Lalor passionately pleaded for after the great Famine, and which I have urged almost in vain upon the acceptance of the Nationalists of my time.

‘Ireland her own’

Davitt is referring here to Fintan Lalor’s famous letter to Gavan Duffy, editor of The Nation (which published it on 24 April 1847 under the title ‘A New Nation’), and his article in the first number of The Irish Felon (24 June 1848) in both of which he warned the Irish landlords to’commit themselves to Ireland, to their tenantry and to the new Social Constitution that he proposed for the country or to perish. What he called in the 1848 essay ‘the first great Article of Association in the National Covenant of organised defence and armed resistance is described in a famous passage:

On a wider fighting field, with stronger positions and greater resources than are afforded by the paltry question of Repeal, must we close for our final struggle with England, or sink and surrender. Ireland her own—Ireland her own, and all therein, from the sod to the sky. The soil of Ireland for the people of Ireland, to have and to hold from God alone who gave it—to have and to hold to them and their heirs for ever, without suit or service, faith or fealty, rent or render, to any power under Heaven. From a worse bondage than the bondage of any foreign government, from a dominion more grievous and grinding than the dominion of England in its worst days—from the cruellest tyranny that ever yet laid its vulture clutch on the soul and body of a country, from the robber rights and robber rule that have turned us into slaves and beggars in the land that God gave us for ours—Deliverance, oh Lord; Deliverance or Death—Deliverance, or this island a desert! This is the one prayer, and terrible need, and real passion of Ireland today, as it has been for ages.

Lalor’s aim was, in one version, grandiose:

Not to repeal the Union, then, but to repeal the Conquest—not to disturb or dismantle the empire, but to abolish it forever—not to fall back on ’82 but act up to ’48—not to resume or restore an old constitution, but to found a new nation, and raise up a free people, and strong as well as free, and secure as well as strong, based on a peasantry rooted like rocks in the soil of the land—this is my object …

In another version, it was more specific. Lalor pleaded for what he called ‘a combination of classes’. The movement for repeal of the Union was, he claimed, ‘a question of the population’; but ‘the land tenure question is that of the country peasantry’. In merging them together in one enterprise, he appeals to the power of the distinction between soil as a material- metaphysical possession and land as a political-legal entity. The nation is of the soil; the State is of the land:

I hold and maintain that the entire soil of a country belongs of right to the people of that country, and is the rightful property not of anyone class, but of the nation at large, in full effective possession, to let to whom they will on whatever tenures, terms, rents, services and conditions they will; one condition, however, being unavoidable, and essential, the condition that the tenant shall bear full, true, and undivided fealty, and allegiance to the nation .. .! hold further … that the enjoyment by the people of this right, of first ownership of the soil, is essential to the vigour and vitality of all other rights … For let no people deceive themselves, or be deceived by the words, and colours, and phrases, and forms, of a mock freedom, by constitutions and charters and articles, and franchises. These things are paper and parchment, waste and worthless. Let laws and institutions say what they will, this fact will be stronger than all laws, and prevail against them.

From there, Lalor goes on to attack the landlords, recommend their removal and the assertion thereby of the rights of eight million people against the selfish interests of a class of eight thousand.

Soil prior to landThe laws of the land are, in this vision, dependent upon the rightful ownership of the soil. Soil is prior to land. It is actual and symbolic, the more symbolic because of its claim to sheer materiality. The romanticnationalist conception of the soil, its identity with the nation, its ownership by the people, its priority over all the superimposed administrative and commercial systems that transform it into land is the more powerful because it is formulated as a reality that is beyond the embrace of any concept. It does not belong to the world of ideas; it gives birth to the idea of the world as a politically and economically ordered system. This formulation had great appeal for leftwing, socialist or proto-socialist activists like Lalor, Mitchel and Davitt. It had equal appeal for those who identified the emergence of a bureaucratic, heavily administered society with intrusive modernity and espoused instead a conservative, reactionary vision of the nation, particularly of Ireland, as an organic territory not conducive to such rationalised ordering. As in the instance of Burke, who regarded administrative rationalisation as an unnatural imposition of inhuman, geometric reason on the natural conditions of the traditional soil of France in the revolutionary period, Irish writers of the post-Famine generation and beyond rewrote the opposition to landlordism and to British rule as a characteristically national repudiation of modernity. ‘Celtic’ land hungerIt is curious that Davitt should have believed that ‘Celtic’ land hunger should have made his dream of national ownership impossible. For the various figurings of national character that are produced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are generally concerned to portray the Celt as dreamy, imaginative, indifferent to the material world. It is appropriate that Lalor should speak in terms of classes and communities, peasants and town-dwellers, because he wrote before the image of the Celt was fully formed. Lalor’s views reflected the material world. However, his very division between peasant and town-dweller, between one who is anchored in the soil and one who is tied to the petty disputes of politics and commerce, was readily recruited into the descriptions of national character that we find, contested indeed but confined within recognisable boundaries, in the writings of Yeats and Pearse, Joyce and Sigerson, William P. Ryan and Thomas MacDonagh. The apotheosis of the peasant and of the Celt easily allied itself with the notion that the soil was a sacred possession, mystically owned by the dispossessed (the peasantry) and disgracefully betrayed by its negligent, rapacious owners (the landlords).

Dracula: the story of an absentee landlord

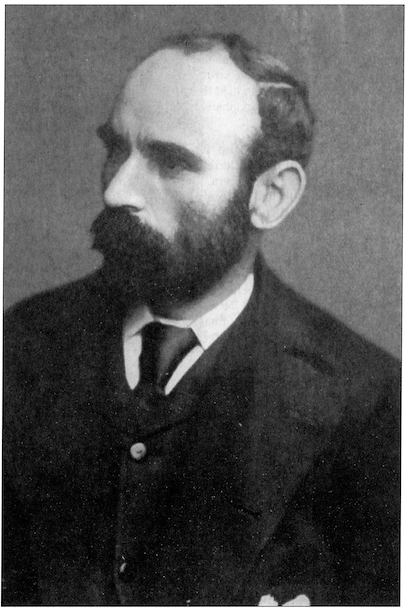

The landlords also had their role to play in this dispute about territory and the nature of the various claimsmanto it. As they lost their grip on the land, they were attacked even by those who believed that they had, or had once had, a right to it that went beyond legal entitlement. The brunt of Standish James O’Grady’s attack on the Irish landlords was that they had contrived to loose their ardour and refinement and become brutish foxhunters, people who had come ‘to despise your birthright … till the very clay of the earth is more intelligent than yours’. The term ‘earth’ , in such a context, denotes something much more inert than soil. It is pure, untransformed materiality. Yet O’Grady does have a version of the potential alliance between peasantry and landlords—later adapted by Yeats—who live in another territory, a Celtic world untainted by actuality, narrativised into legend but not into history, where it is always dawn or twilight, never monotonous daylight.

A nation’s history is made for it by circumstances, and the irresistible progress of events; but their legends, they make for themselves. In that dim twilight region, where day meets night, the intellect of man, tired by contact with the vulgarity of actual things, goes back for rest and recuperation, and there sleeping, projects its dreams against the waning night and before the rising sun.

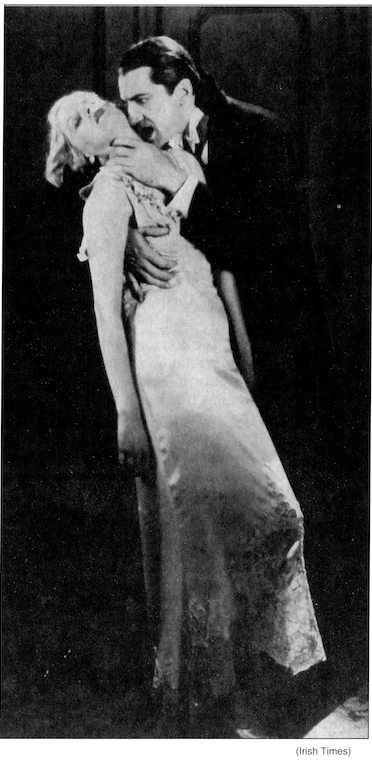

This is obviously Yeatsian, even to the uncertain grammar of the first sentence and the premonitory indication of the political and cultural uses to which the poet was later to put occult theory and its fetish of dawn, twilight, sleep, dream. It is also a recognisable moment in the long evolution of Protestant Gothic which was, like Catholic Nationalism, always seeking for a rhetoric that would both providing an analysis of the political question of land and land ownership, and a simultaneous account that would transpose its intractable features into another language. After all, Gothic fiction is devoted to the question of ownership, wills, heirs, testaments, hauntings of places formerly owned. Its most commercially successful manifestation, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), tells the story of an absentee landlord who is dependent in his London residence on the maintenance of a supply of soil in which he might coffin himself before the dawn comes. He moves, like an O’Grady version of the Celtic hero, between dusk and dawn; but, landlord that he is, with all his enslaved victims, his Celtic twilight is endangered by the approach of a nationalist dawn, a Home Rule sun inexorably rising behind the old Irish Parliament. Dracula’s dwindling soil and his vam-piric appetites consort well enough with the image of the Irish landlord current in the nineteenth century. Running out of soil, this peculiar version of the absentee landlord in London will flee the light of day and be consigned to the only territory left to him, that of legend. Like O’Grady’s and Yeats’s Anglo-Irish, he will be evicted from history and relocated in the never-never land of myth. He will be demonised more covertly but also more effectively than by the overt rhetoric of a Lalor, Mitchel or Davitt. Caught between geography and historyUltimately, the question of the land and its relation to the soil lost its force as landlordism faded and tenant-proprietorship became common. Owner occupation closed the gap between soil and land. But it left a deficit that had to be met. The territory of Ireland, with all its nationalist and all its gothic graves, with all its mouldering estates and emerging farms, its Land Acts and its history of confiscations, was in need of redefinition by the early years of the century. Exile, the high cultural form of emigration, became one of the most favoured strategies for the representation of Ireland in the early twentieth century. It was a form of dispossession that retained—imaginatively—the claim to possession. It was also a position from which a critique of the ‘peasant’ view of Ireland could be mounted. It was, in effect, a position occupied by writers of the ‘town population’—Dubliners like Shaw, Wilde, O’Casey, Beckett and Joyce, the most famous of Irish exiles in this regard. For Joyce’s Dublin, the Ireland he wrote of, was, in an important sense, a nowhere, a territory not yet represented, caught between geography and history. His sense of place was haunted by displacement. In A Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man, Stephen experiences just this sensation as he approaches 86 St Stephen’s Green, the site of University College. The house once belonged to an anti-Catholic Anglo-Irishman, Buck Whaley. Now it belongs to the Jesuits. But Stephen’s experience, which immediately precedes the disturbing episode with the Dean of Studies, is of a place in which history has receded from geography, poised between two dispensations, an interstitial absence: The corridor was dark and silent but not unwatchful. Why did he feel that it was not unwatchful? Was it because he had heard that in Buck Whaley’s time there was a secret staircase there? Or was the Jesuit house extraterritorial and was he walking among aliens? The Ireland of Tone and of Parnell seemed to have receded in space. This, along with the subsequent alienating conversation with the Dean, is a critical moment in Stephen’s obverse vision of Ireland. Previous to this, his walk through the city, from north to south, had been a soothing exercise in the rhetoric of familiarity; now this is abruptly displaced by the rhetoric of estrangement. Neither cancels the other. They subsist together. A territory is possessed and then the possessor of it is dispossesed. Exile is the other side of home. It was at such moments in his fiction that Joyce rewrote the idea of national character and replaced it by the idea of a character in search of a nation to which he could belong. The convergence of the geography of Dublin and the history of Ireland produces extraterritoriality. Moreover, with Joyce the citydweller, the construction of Ireland passes from the inhabitants of the land to those of the town. Lalor’s land and soil is exchanged for a Parnellite’s vision of a city that comes to represent both Ireland and the whole condition of modernity.

Seamus Deane is Keough Professor of Irish Studies, University of Notre Dame, Indiana.

Further reading:

M. Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland (Dublin 1904).

S. Deane et al (eds.), The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry 1991), Vol. II, pp. 172-74,280,525-6.

N. Marlowe (ed.), James Fintan Lalor: Collected Writings (Dublin and London 1916).

G. Sigerson, Modern Ireland; Its Vital Questions, Secret Societies and Government (London 1868).