By Kieran Rankin

Among the artist Lilian Lancaster’s renowned array of artfully drawn and vividly coloured maps of Ireland are some instances that combine Irish figures such as St Patrick with the map image of Ireland in a distinctive folkloric style. In contrast to more common feminised representations of Ireland in the form of Erin and Hibernia, the anthropomorphic maps introduced here show either St Patrick or the male Irish peasant as the predominant focus of Lancaster’s portrayals. The maps exhibit clear evidence of the artist’s inspiration from earlier works of the genre and of her own evolving style. They not only served an educational and entertaining purpose but also underlined Ireland’s archetypical associations with, for example, the colour green, Christianity and shamrock, both individually and in combination.

EARLY CAREER

Born in London in 1852, Lilian Lancaster first came to public notice in 1868 as the unnamed ‘young lady … in her fifteenth year’ who illustrated Geographical fun: being humorous outlines of various countries with twelve maps of various European countries. This book mentions that Lancaster’s original motivation was to cheer up her ill brother, and it includes a map of Ireland as an Irish peasant woman laden with a basket, a metal box and a simian-jawed baby holding a fish (HI 29.1, Jan./Feb. 2021, p. 22).

Lancaster embarked on a theatrical career from 1872 as a pantomime actress and variety show performer, which involved extensive touring across Britain and Ireland, including starring as Aladdin at Dublin’s Theatre Royal in 1876. In February 1880 her growing renown earned her a featured profile in the London-based weekly magazine The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, in which reference was made to audiences being entertained by her rapid sketches of celebrities of the day. During an American tour later that year, she drew a topical caricature satirising the upcoming presidential election between Republican candidate James Abram Garfield and Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock by representing them as squabbling children in girls’ dresses against the backdrop of a map of the United States.

A GENERIC IRISHMAN MAP

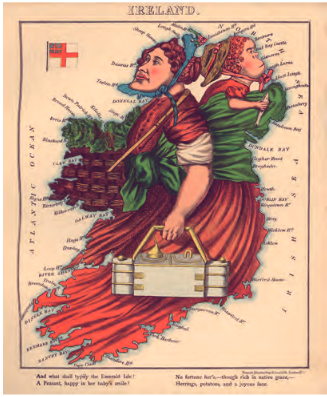

Lancaster was commissioned by pen manufacturers Ormiston & Glass, an Edinburgh company, to produce a map titled ‘Ireland—A Comic Geographical Sketch’ (p. 37). The lithograph was printed by Scott & Ferguson, also of Edinburgh. Lancaster’s authorship is indicated by the inscription ‘LANCASTER DEL[INEAVI]T’ (Latin for ‘Lancaster drew it’); while the map is undated, it probably appeared in 1884 or earlier, as from then on she signed later works under her married name of Tennant. (Versions for England and Scotland also exist but, while clearly exhibiting Lancaster’s style, show no definitive attribution or dates.) In the title, the capitalised letters of the word ‘Ireland’ are coloured green with black outlines, with the initial ‘I’ having a gold harp embedded in its vertical bar and shamrocks in its horizontal bars, with each following letter then having a shamrock attached to the left. This map shows a red-haired simian-jawed man with a pipe in his grinning mouth, wearing a black hat with a green band and leaning against a red-brick wall. He is backed by an unconventionally shaped golden harp, speckled with shamrock and with mermaid creatures embedded in its body, that occupies the eastern Ulster and Louth sections of the map. The man’s clothes throughout (green coat, red waistcoat, brown breeches and striped grey stockings) show a poor state of wear and tear, conveying an impoverished condition. Held in the man’s right arm is a young red-haired girl to the west, possibly the man’s daughter, wearing a blue dress with a pink petticoat. She grips his dotted brown scarf with one hand and holds a fish in the other. The man wields a brown shillelagh/cudgel between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand; by his black shoes, among some flowers and grass, is a small pig, rearing on its hind legs in anticipation, with its front trotters resting on the man’s leg.

The overall characterisation is evocative of Lancaster’s first map of Ireland in 1868 and strongly leans towards a stereotypical rural depiction of a poor Ireland within the then United Kingdom. The map itself is a derivative homage to Robert Dighton’s 1793 ‘Geography Bewitched’ (see HI 29.1, Jan./Feb. 2021, p. 20). Both of these feature rural peasants with children holding foodstuffs, and Dighton’s map of Ireland also features a prominent golden harp. From a cartographic perspective, there is a significant expanse of space for the inscribed Atlantic Ocean, North Channel and Irish Channel (the latter in place of Irish Sea), but it is notable that the map of Ireland is isolated by excluding what would be the geographically accurate rendering of Scotland’s neighbouring shores altogether. There are also a few curious anomalies, such as Birterbury Head in Galway, which would be now commonly known as Bertraghboy Bay, as well as the only mononym amid all the many inscribed bays, estuaries and headlands being Rush (Co. Dublin), whose name in Irish, ‘Ros’, can mean a (wooded) height, wood or promontory. These give hints as to the possible source and/or date of the conventional base map that Lancaster had probably adapted.

A PROTOTYPE ST PATRICK MAP?

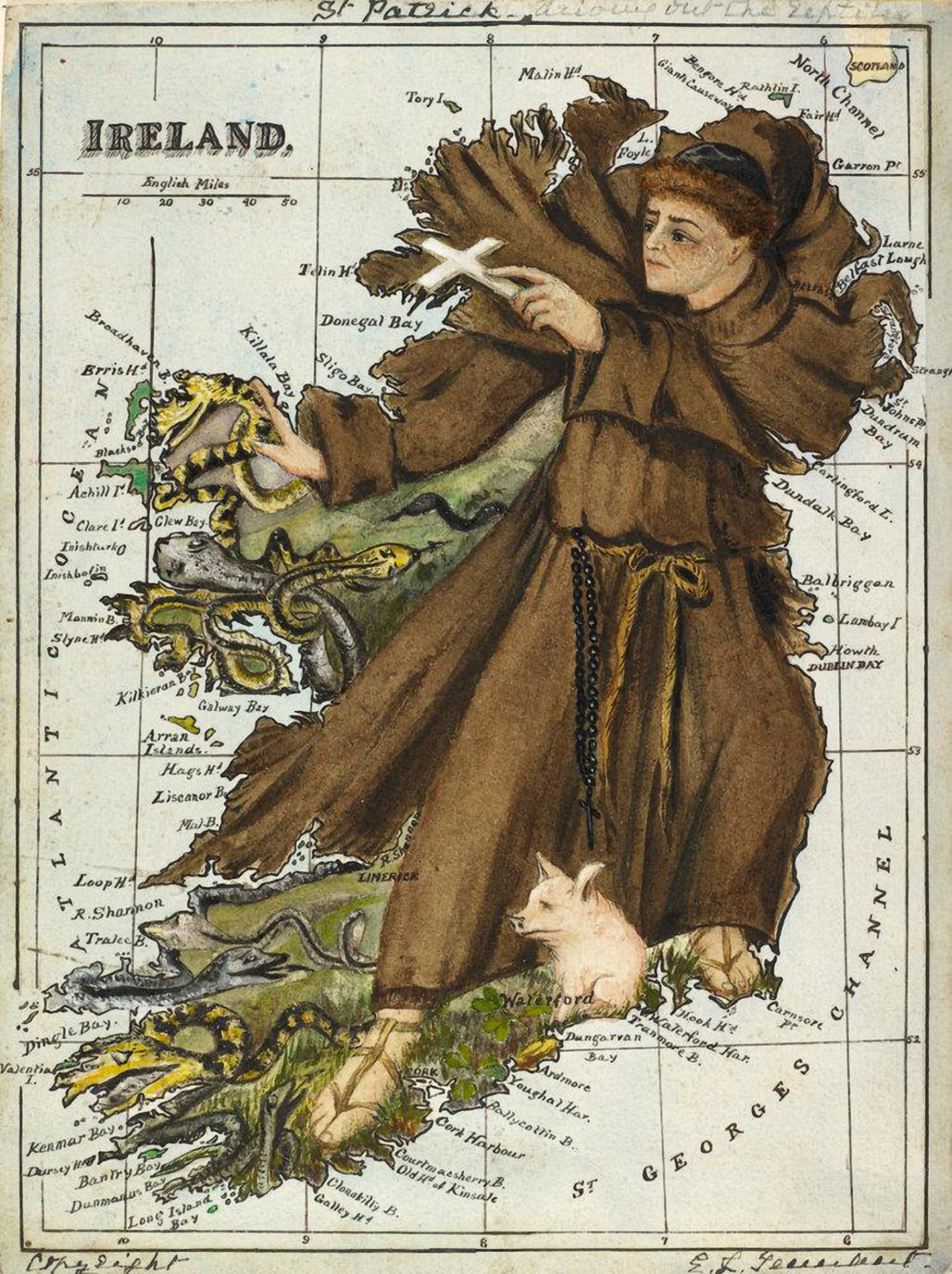

Lancaster had retired from the stage following her marriage in 1884 but proceeded to produce a flurry of unpublished maps, including of France and of Spain and Portugal, that are now held by the British Library. One of these is titled ‘St Patrick, driving out the reptiles’ (p. 38) and is executed in watercolour with ink. Although a handwritten ‘Copyright’ in the lower left corner would signal an intent for publication, no other editions of this map appear to exist. Although clearly hand-coloured and inscribed, it displays the orthodox conventions of a printed atlas map, with longitudes and latitudes shown as well as a scale. Tightly enclosed by its outer border, Scotland’s Mull of Kintyre sneaks into frame and, while the Atlantic Ocean and St George’s Channel are named, the Irish Sea is not. Other curious inconsistencies also appear on the map in that Belfast, Cork, Limerick and Waterford are the only places of the interior inscribed while Dublin is not (although the capitalised ‘Dublin Bay’ is).

Standing in combative pose, a russet-haired and clean-shaven St Patrick dominates the map, which renders the renowned hagiographic episode in which he expelled Ireland’s reptiles. Dressed in a plain brown habit along with windswept shoulder-cape, he wears a black zucchetto on his head and a bow-tied cincture girdled around his waist, from which some black rosary beads are draped. With his right hand in a gesture of repulse, his left brandishes a white crucifix, while both are directed at, as the faded handwritten subtitle describes, ‘driving out the reptiles’ to the west and south-west. The vignette is completed by the presence of a pig by Patrick’s thinly strapped sandalled feet, which probably references his past as a swineherd.

AN ARCHETYPAL ST PATRICK MAP

Lancaster’s artistic talents were summoned again for the 1912 book Stories of Old London, authored by Elizabeth Louisa Hoskyn. Aimed at the younger reader, the book adapts twelve tales from countries of Europe that highlight a particular historical event or legend strongly ingrained in each country’s literary tradition. To add further to the imagination, each is also illustrated with a map depicting key characters and events within the outline of the country’s boundaries, such as ‘St George Wins the Victory Over the Dragon’ (England) and ‘The Children Follow the Pied Piper’ (Germany).

For Ireland, to accompany an account of the life of Ireland’s patron saint, Lancaster significantly reworks her previous watercolour map of Ireland illustrating St Patrick’s banishment of the snakes. The result is a sharper and more detailed rendition titled ‘St Patrick Commands All the Reptiles to Leave Ireland’ (p. 39). While retaining some of the same cartographical conventions such as longitude and latitude (but not the scale bar) of her previous edition, this one does label the Irish Sea, as the frame and the map’s proportions allow more space to be represented.

The tale starts by referring to the illustrated hexagonal ‘strange rocks’ of the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland’s north-east before chronicling the story of St Patrick himself. He is fully dressed in ornate and heavily layered clerical vestments that include a dark green chasuble with an embroidered orange brocade and golden hem, all overlain by a white pallium, with black crosses (of the pattée fitchée type), symbolising his episcopal authority. In even more stark contrast with the austerely attired Patrick of before, an older, white-bearded St Patrick here is equipped with a bishop’s crozier (in classical shepherd’s-crook form) and his head is capped with a bejewelled and embroidered pretiosa mitre. A white halo radiating golden light circles his head, as was often rendered in historic artistic representations of holy figures.

With a gesture of benediction, Patrick calmly confronts Ireland’s snakes as per the hagiographic legend, as the tale informs the reader that he is ‘bidding them begone. Look how the snakes are rearing themselves up against him! yet they will have to go.’ Also behind by his feet are a couple of pigs, as opposed to the solitary one in the earlier rendition, again referencing Patrick’s swine-herding past. In pointing out the shamrock entwining Patrick’s crozier, the tale also includes the shamrock fable—the metaphor by which the Christian concept of the Holy Trinity is described. Although acknowledging some uncertainty over the original legend, the tale affirms that ‘if he did not drive out the snakes and toads he did a much better thing for Ireland, for he taught her people the Christian Faith, and for this reason he will always be loved and remembered’.

CONTEXTS AND OVERVIEW

Lilian Lancaster’s calling as a cartographer appears to have been appropriately book-ended by collections of various European countries published in illustrated books ostensibly targeted at children. Creatively designed and brimming with vivid detail, her anthropomorphic maps of Ireland exhibit several layers of mutually reinforcing symbolism and meaning. As all four of them were part of wider collections of other countries and not specifically aimed at an Irish readership as such, they only represent a small sample of her ranging canon of coverage. Nevertheless, there is a great deal to discern and extrapolate about how Ireland and aspects of ‘Irishness’ can be projected to a wide readership.

Their educational utility as conventional maps is initially made explicit by the projection of the map image that emphasises the shape of Ireland. While depicting the key scene means mostly foregoing the inscription of places within Ireland’s interior, this allows for Ireland’s coastal land-forms to be more pronounced and liberally indicated. Obviously, each of Lancaster’s maps necessarily involves considerable creative licence. After her earlier, more stereotyped characterisations of the Irish as simian-jawed peasants in a rural and impoverished setting, she later elects to show a hagiographic and anachronistic depiction of the fifth-century Patrick in more modernised liturgical dress.

In her profile of Patrick, Alannah Hopkin credits the ‘Irish people’ as having ‘in the late eighteenth century, chose[n] the colour green, the shamrock and Saint Patrick to symbolise their separate identity as a nation’. All three of these elements permeate Lancaster’s map canvas and entrench a nexus of already well-established and widely recognised symbols. The grass background and Patrick’s green chasuble in the 1912 map also play into the enduring ‘Emerald Isle’ epithet. The selective use of shamrock allows not only for the colour green but also for Christian religious undertones to be conveyed. Of course, Patrick himself, his name already conferred on many places and features throughout the Irish landscape, is shown as figuratively encompassing the island of Ireland and thus embodying a primacy as a marker of both Irish identity and the Christian religion—indeed a transcendent national symbol. This is all despite the ironies that neither the name Patrick nor Patrick’s early life are Irish in origin.

Considering the perennial strength and durability of the traditions linked to St Patrick that have augmented religious and national identity, the folklorist Jenny Butler has observed that the ‘close connection between St Patrick and emblems of national identity such as the shamrock and the colour green makes these customs more authentic and valid in popular understandings of folk tradition’. Nevertheless, whether projecting St Patrick as a peerless Irish icon or leaning into the more generic Irishman stereotype, Lilian Lancaster’s imagination in these cartographical curiosities not only exemplified that the very map of Ireland can be deployed as an appropriate and powerful motif but also is testament to the map as a versatile art form.

Kieran Rankin is a political and historical geographer currently working in Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

‘Aleph’ [William Harvey], Geographical fun: being humorous outlines of various countries (London, 1868).

R. Barron, ‘Lilian Lancaster (1852–1939)’ (http://barronmaps.com/lilian-lancaster-1852-1939/).

J. Butler, ‘St Patrick, folklore and Irish national identity’, in A. Heimo, T. Hovi & M. Vasenkari (eds), Saint Urho—Pyhä Urho—from fakelore to folklore (Turku, 2012), 84–101.

A. Hopkin, Patrick: from patron saint to modern influencer (Dublin, 2023).