By Fiona Fitzsimons

Official attitudes to emigration were cautious. The state viewed it as stripping skilled workers from the economy and weakening economic growth. Its main contribution was in social engineering: in cities, the ‘idle poor’ were rounded up and shipped out; convicted criminals and debtors were transported to the American colonies and, after 1791, to Australia. Officials called these unwilling emigrants ‘waste people’ who would ‘manure’ the uninhabited ‘wasteland’. The practice continued into the twentieth century with the Home-Child scheme. Despite, or perhaps because of, official attitudes to poor emigrants, there was no effort to keep records of those who left, and we only have scattered short runs.

In 1890 the Board of Trade began keeping complete records of all passengers leaving the UK, including Ireland. Between 1890 and 1922 we have full records of everyone sailing from Irish ports, and from 1922 to 1960 for passengers departing from Belfast and Derry in Northern Ireland. These were long-haul passengers, bound for destinations beyond Europe, often to distant outposts of the British Empire. A closer look reveals evidence of Ireland’s long tradition of sending religious missionaries overseas. In August 1956 a group of nuns from the St Louis Convent in Monaghan appear in the records: Sheela Agnes Gillespie, teacher (born 24 May 1912), bound for the Gold Coast (Ghana); Mary Moane, teacher (born 7 November 1920), and S.M. ‘Chrysostom’ O’Daly (born 5 July 1912), both bound for Nigeria. Although they took new names on entering religious life, their passports were issued in their birth names.

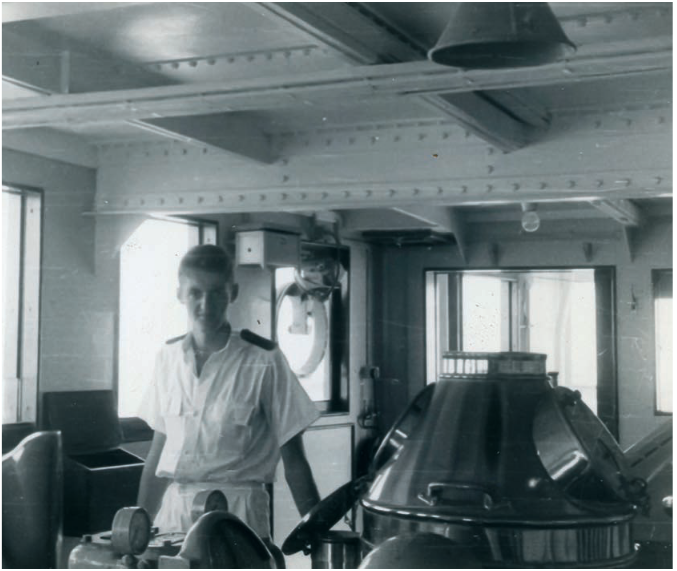

The crews of Royal Navy and merchant navy vessels are not listed in these records but we can find sailors travelling to join their ships. In 1956, for example, Brian Fitzsimons, 24 years old, a merchant navy radio officer, appears travelling on an Irish passport aboard the P&O liner Corfu, bound for Singapore. His country of residence for the previous and following twelve months was simply recorded as ‘at sea’.

There is no single standard format for a passenger list; the data captured change over time, and many shipping lines used their own pre-printed forms. Nevertheless, all records include at a minimum the passenger’s name, sex, age, marital status, occupation, date and port of departure, the destination port and country, the ship’s name, the ship’s master and the number of passengers onboard. Later records often have additional evidence, including the passenger’s date of birth, last residence and intended residence. For November and December 1960 there are sea departure cards, which have more biographical evidence and, critically, the person’s signature.

These records document 24 million passengers, telling us that movement across borders is woven into the fabric of human history and human nature alike.

Fiona Fitzsimons is a director of Eneclann, a Trinity campus company, and of findmypast Ireland.