By Joanne Rothwell

On 29 March 1941 a circular letter transmitting ‘Emergency Powers (No. 73) Order, 1941’ to local authorities was sent out by the Department of Local Government and Public Health. It empowered local authorities to compulsorily acquire bogland for the purposes of exercising by direct labour a right of turbary over the land. They were given the responsibility of closing the huge gap in energy supply that had arisen through the massive reduction in coal imports from the UK. Doubts were raised by Patrick Baxter, TD for Cavan, in a Dáil motion to annul the order on 3 April 1941:

‘At this stage I would like to say that I am in favour of local authorities like county councils, in a limited way, taking upon themselves the responsibility of providing from bogs within their domain a quantity of fuel that will be sufficient, say, for their machinery or even for their institutions. If they can do that, it is all to the good. In attempting to carry out even a scheme like that there are certain limitations. You cannot send anybody at all into a bog and be satisfied that he is going to give a good return for his time there. Quite the contrary. I am not quite clear how many of our county or assistant engineers are competent to plan and to carry out the kind of work required in bogs.’

In spite of these misgivings, and in light of the desperate need for fuel to supply institutions and homes, the county surveyors took on the task and rose to the occasion admirably. Waterford County Council offers an interesting case-study, as it took up turf production directly in response to the order and its bogs were ‘few and far between’. On 1 August 1941 the Munster Express carried a report from Waterford County Council’s meeting at which Commissioner Simon J. Moynihan paid tribute to the county surveyor, John Bowen, and his staff for the great progress made on the turf scheme.

As an incentive to county surveyors and their staff, the Department of Local Government and Public Health provided bonuses for turf production. These bonuses were to be charged against the cost of turf production. In Waterford County Council the ‘Record of Expenditure on Road Work Executed by Direct Labour’ was repurposed as the ‘Turf Account Book’. Waterford County Council acquired turbary rights in Knocknaree and Boola, Comeragh Mountain, Kilcannon, Reamanagh East, Knockalougha and Knockaveelish, and in Garrynagree, having issued the required vesting orders on 16 and 26 April 1941.

The logistics of getting the turf out did present difficulties, however: getting to the turf, finding men available to cut it and transporting it were all hurdles that needed to be overcome. On 23 May 1941 John Bowen, Waterford’s county surveyor, wrote to the secretary of the Department of Local Government (Turf Section):

‘In this county men are very scarce, and the bogs are also few and far between. Every available man is at the turf cutting. The making of these bog roads is now a matter of vital urgency, as without them the turf could not be got out.’

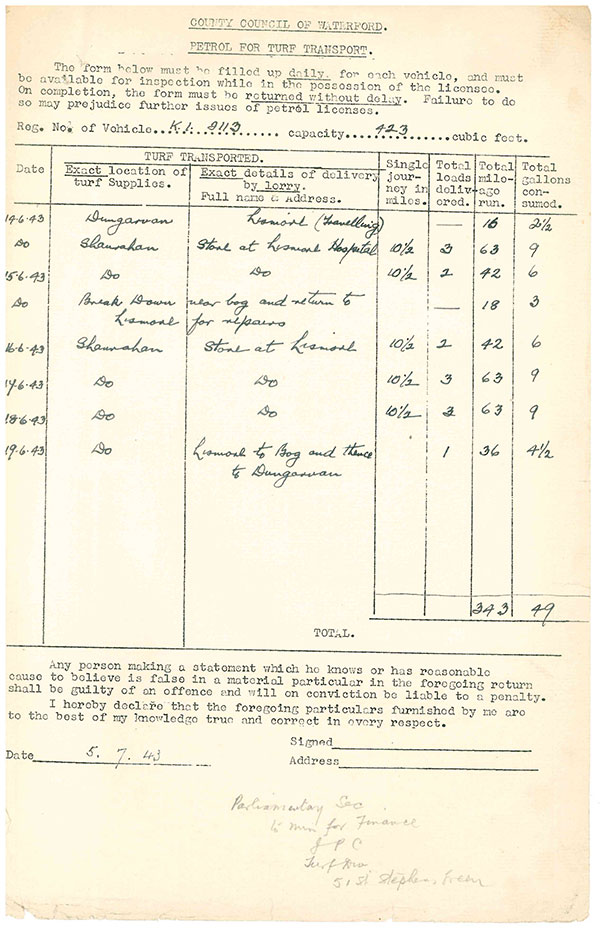

Once the road was built, the turf had to be transported, and this required the use of the limited petrol supplies.

The turf harvested was used by the council’s machinery yard, by the County Home and by the district hospitals as a priority. In May 1944 Councillors Michael O’Regan and David Coughlan complained that the people of Kilmacthomas, who could not buy turf directly from the bogs of County Waterford, had to watch turf arriving from Kerry pass through their station without stopping and then pay extra to get it sent back to them from Waterford.

The drying and storage of turf for later distribution not only was a logistical problem but also presented a dangerous hazard. Tall cairns of turf had been stored against the wall of Ballybricken Jail and on 4 March 1943 the wall collapsed, crashing onto a row of small houses on Kings Terrace. The collapse occurred during the early hours of the morning and ten people were killed, with many more injured. A special meeting was convened on 9 March 1943 by the mayor, Alderman Paul Caulfield, to raise funds for the many families who had lost their homes and loved ones.

Turf production largely operated at a loss throughout the Emergency and required an ongoing overdraft accommodation. On 2 August 1946 Waterford County Council’s acting county surveyor reported that he had 3,468 tons of turf on hand, of which 1,800 were on the bog. The total value of the turf was £9,262 and the turf overdraft was £14,436. The accumulated loss since the inception of the scheme was £4,600. The county manager reported that the recoupment of the loss would be addressed at the conclusion of turf-cutting operations. The turf campaign did not come to an end in Waterford County until 20 October 1951, when the last payment was made in the Turf Account Book.

Although beset by the expense and difficulties of production, the turf campaign did succeed in offering much-needed work and provided fuel to offset the increased costs and difficulty of meeting demands on the limited coal and petrol supplies available. The records of turf production in local authorities provide an insight into the impact that the lack of supplies during the Emergency had in Ireland and the coming together of central and local government in an effort to keep the lights on.

Joanne Rothwell is Waterford City and County Archivist and a member of Local Government Archivists and Records Managers (LGARM) and the Archives and Records Association (ARA).