By Fiona Fitzsimons

The Local Government (Ireland) Act, 1898, swept away the existing system of county government, grand juries and Poor Law boards. It introduced a new two-tier structure of local government, with county and city boroughs on the first tier, and urban and rural districts below them. It introduced democratically elected councils to manage the administrative and financial duties of local government, while responsibility for social welfare and health remained with the Poor Law authorities and judicial matters with the grand juries. It reformed the local government franchise for cities and the larger towns, extending it to all men over 21, and to women over 30, who met a property qualification. The franchise reforms brought tens of thousands of new voters, including women, into local politics for the first time. Women could now stand for election to urban and rural district councils, though they were not eligible for county and city councils until the Local Authorities (Qualification of Women) Act, 1911. After 1898, local elections were reorganised on a three-year cycle, except for borough and urban district councils, which continued with annual elections until 1919.

The Local Government (Ireland) Act, 1898, became effective in August of that year. The city councils began the process of registering eligible voters, including:

- rated occupiers and resident householders: owner/occupiers of business or residential properties had to show that the annual rateable valuation of their property met a minimum threshold of £4;

- freeholders and leaseholders;

- lodgers: under the Act, lodgers either had to pay rates themselves or be listed on the rate register;

- freemen: The descendants of all former freemen were themselves eligible by birth. This legacy of the medieval guilds was only closed by the Representation of the People Act, 1918.

The electoral rolls are broken up by county, divisions and wards. Voters were grouped within their ward by category, i.e. parliamentary and/or local government voter, and then by qualification, e.g. lodger, freeholder etc. The record of every registered voter includes their full name, address and criteria for eligibility. There is some additional information in these categories. Lodgers had to provide the name and address of their landlord; to describe their rooms or lodgings, including whether furnished or unfurnished; the rent they paid; and what they received in board and lodgings.

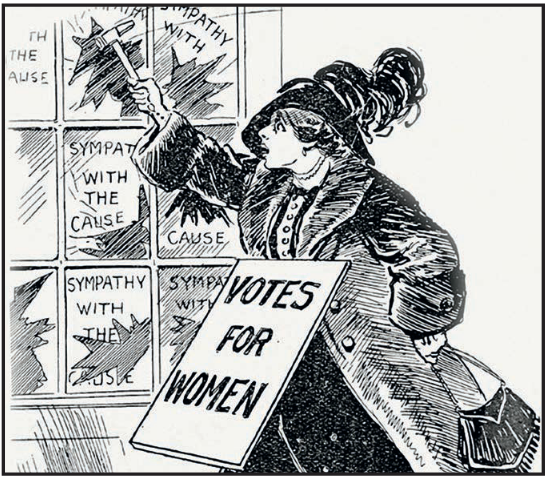

The Irish Women’s Suffrage and Local Government Association (IWSLGA) led a campaign to register female voters. We find Anna Haslam, secretary of the IWSLGA, writing to newspapers to remind women to use their vote. Working with the electoral rolls, it is clear that the property qualifications were not always strictly adhered to. Lodgers were supposed to occupy a room valued at 4s. a week, or £10 per annum; they should be resident for a whole year before the register was updated; and they should have a contract with their landlord, although they didn’t have to pay rent. Moreover, they had to request to be assessed for inclusion. In many instances we find adult daughters prevailing on their parents to register them as lodgers so that they were eligible to vote. In 1913 we see sisters Miss Maria Josephine Robinson and Miss Ellen Cope Robinson, registered as lodgers, leasing furnished rooms, ‘no rent by agreement’, in the family home, 22 Palmerston Park (Rathmines Ward). Their father, Archibald Robinson, was also eligible to vote as a freeholder. In fact, the only member of the family who didn’t have a vote was their mother, Mrs Maria Josephine Robinson.

The reform of the local government franchise was a transitional moment in Irish political life, preparing the ground for the Representation of the People Act, 1918.

Fiona Fitzsimons is a director of Eneclann, a Trinity campus company, and of findmypast Ireland.