By Emily Mark-FitzGerald and Kathryn Milligan

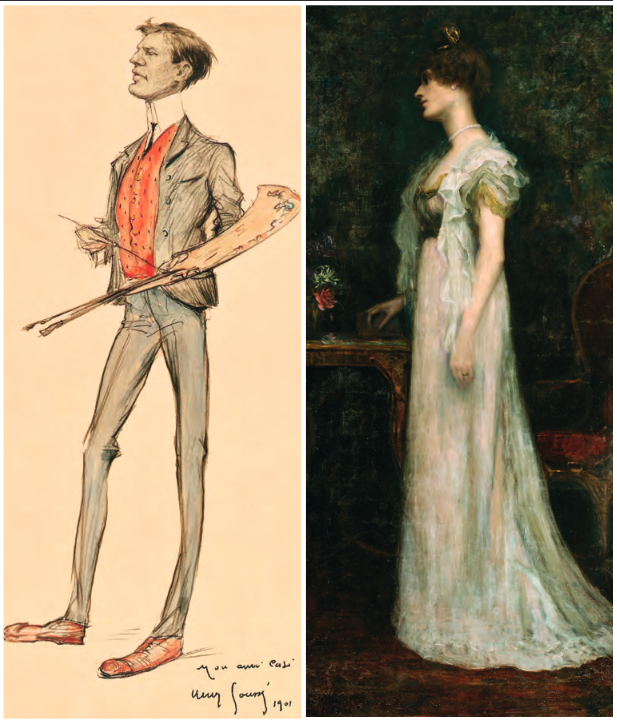

On a Paris evening in early 1899, two Polish friends arrived at a ball attended by fellow international art students, drawn to the hedonistic atmosphere of the fin-de-siècle city and its artistic charms. One of the young men—the writer Stefan Krzywoszewski—was struck by a young Irishwoman present, ‘who appeared to be about twenty years of age … conspicuous for her proud bearing. She was a living Rossetti or Burne-Jones.’ Seizing his friend Casimir Markievicz, he insisted, ‘Do dance with this lady. You will be well matched in height and bearing.’ Thus began one account of the first meeting of Constance Gore-Booth (1868–1927) and Casimir Markievicz (1874–1932), who married in 1900 after a whirlwind courtship in Paris.

In Ireland, the name ‘Markievicz’ instantly conjures up the figure of Constance, the daughter of Anglo-Irish gentry of Lissadell House, Co. Sligo, who was destined to become one of Ireland’s revolutionary heroines. An art and historical exhibition in Dublin Castle—Casimir Markievicz: A Polish Artist in Bohemian Dublin (1903–13)—which opened in April 2025 seeks to bring Casimir back into the frame, restoring him as a central player in Dublin’s bohemian life before the revolution. Casimir’s life, art and theatre connect the histories of Poland, Ukraine and Ireland, and their parallel quests for independence and self-determination.

Casimir’s background in a Polish landed family settled in Ukraine mirrored Constance’s upper-class upbringing, and both sought to rebel against bourgeois society in adopting an unconventional lifestyle and marriage. From 1903 to 1913 ‘Casi and Con’, as they affectionately called one another, made Dublin their home. In a city teeming with rival theatrical factions, writers and visionaries of the Irish Revival, they pursued their artistic ambitions. Cycling around Dublin with paint and canvases strapped to their bicycles, they revelled in (and led) its avant-garde clubs and salons, whilst also gliding amongst the élite of Dublin Castle. It was a decade of competing visions of what art could be, of how theatre and art might inform politics (and vice versa), and what fate lay ahead for Ireland as a nation.

Casimir and Constance’s involvement in Dublin’s cultural endeavours crossed social and class divides. As skilled painters, the couple were enthusiastic supporters of Hugh Lane’s project for a municipal gallery of modern art and his ambition to bring Continental art to Dublin. Their regular exhibitions with George Russell (AE) and others from 1904 to 1913 became a key part of Dublin’s art calendar. They were co-founders of the United Arts Club in 1907, along with Ellie Duncan, W.B. Yeats, John M. Synge and others. From 1908 they wrote and staged plays and set up numerous theatre companies in the city, at times attracting the ire of Yeats and Lady Gregory for rivalling the Abbey Theatre’s claim on national audiences. A magnet for the city’s artists, writers and performers, Casimir was a larger-than-life presence in its gatherings. Towering over 6ft in height, his reputation for boisterous partying and his passion for theatre made him a popular and highly visible figure in the city. At the same time the couple were part of the fashionable ‘Dublin Castle set’ who attended regular balls hosted by figures such as the Earl and Countess of Dudley (viceroy and vicereine, 1902–5).

Perceived as an exotic ‘foreigner’ in Dublin, Casimir’s congeniality and general disinterest in politics enabled him to move easily between these opposite worlds—ones that by 1908 Constance could no longer reconcile. As she became radicalised within the Irish revolutionary movement, their relationship grew distant and they separated (but never divorced) in 1913. Nevertheless, the exhibition reveals the many threads linking the pair. Constance’s own political awakening was significantly influenced by Polish nationalism and her experiences of visiting Casimir’s family in Ukraine; the exhibition includes numerous paintings by both of them of Ukrainian scenes, many of which have never been exhibited in Ireland since their original creation.

The exhibition is drawn from paintings, drawings, photographs and objects in the public collections of the National Gallery, the Crawford Gallery, Model in Sligo, the Hugh Lane Gallery, the National Museum, the National Library, the Pearse Museum, UCD Special Collections and the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, along with works from private collections including those of Lissadell House, the United Arts Club and Sir Josslyn Gore-Booth. It includes paintings and photographs from the Malkievicz and Libicki families (Markievicz family relations and the inheritors of his legacy), including little-known photographs taken by Constance of Ukrainian landscapes and people. Sponsored by the Embassy of Poland in Ireland and co-produced with the OPW/Dublin Castle, the exhibition testifies to the irrepressible spirit of Casimir Markievicz, embodied in the motto of the Dublin ‘Reality League’ club that he founded: ‘Long Live Life!’

Casimir Markievicz: A Polish Artist in Bohemian Dublin, curated by Prof. Emily Mark-FitzGerald (UCD) and Dr Kathryn Milligan (NCAD), is on view in the State Apartment Galleries of Dublin Castle until 14 September 2025.