By N.C. Fleming

The prospect of Irish unification has received greater attention since Brexit. Much has been made of the willingness of some northerners from a unionist background to discuss how it could take shape. Though it might seem unprecedented, it is not a novel development. The 7th Marquess of Londonderry (1878–1949) was a long-standing member of the Ulster Unionist Council (UUC) and a minister in the first government of Northern Ireland. He later served in the British cabinet as secretary of state for air. He was for many years a hesitant partitionist.

Londonderry was regarded by contemporaries as a moderate Ulster unionist. As such, he was never fully trusted by hard-liners in the movement. At the same time, he was respected by politicians and statesmen in southern Ireland, including Michael Collins, W.T. Cosgrave and Kevin O’Higgins. The latter even floated the idea in 1926 that Londonderry become the viceroy-type figure of a ‘Commonwealth of Northern and Southern Ireland’. Londonderry’s moderation has led some historians to dismiss him as an aberration, but the pragmatic, anti-populist strain of Ulster unionism that he articulated both preceded and succeeded him, albeit in the shadow of its more vocal and populist counterpart.

FORMATIVE VIEWS

Londonderry’s parents were immersed in Ulster unionism. The 6th marquess had been viceroy of Ireland between 1886 and 1889. From 1912 he was often found at Sir Edward Carson’s side at the Ulster unionists’ large set-piece demonstrations. Londonderry’s mother was for many years a leading figure in the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council. Before inheriting the marquessate from his father in 1915, the 7th marquess was known by the courtesy title of Viscount Castlereagh. In his maiden speech as MP for Maidstone, delivered in February 1906, he articulated a formula that he repeated with some variation for almost a quarter of a century and which would have a significant bearing on his attitude to partition, namely that he was in ‘sympathy with the claim that Ireland should be ruled according to Irish ideas, but [he] insisted that they should be consistent with the unity of the Empire’.

When, however, partition was first mooted in the House of Commons, by Thomas Agar-Robartes, in June 1912, Castlereagh’s initial reaction was that he had ‘no sort of idea’ why the Liberal MP for St Austell had proposed it, especially as he had not addressed ‘the machinery which was necessary to carry out his object’. He nevertheless welcomed it as an opportunity for the House to realise ‘that there is a deep-seated and a passionate feeling on the part of the community which lives in the province of Ulster’.

THE FIRST WORLD WAR AND PARTITION

In the wake of the Easter Rising, David Lloyd George held separate talks with Carson and the leader of the Irish nationalist party, John Redmond. Out of this emerged an agreement to implement Home Rule with the proviso that the six north-eastern counties would be excluded, though what each of the Irish leaders knew about the likely duration of exclusion is not altogether clear. In June 1916, hundreds of UUC delegates gathered on two occasions to give their judgement on the deal. These were difficult meetings, but a majority fell in behind the abandonment of both southern unionists and Ulster unionists in the outlying counties of Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan.

Like his late father, the 7th marquess allied himself to Carson and the east Ulster heartland of northern unionism. His rationale, however, was grounded in the need to settle the Irish question for the sake of securing victory in the First World War. Southern unionist opposition to the agreement—which ultimately undermined it—reached Londonderry through his wife. In disagreeing with her, he admitted that the war meant that he would still support the deal even if exclusion was less permanent than Carson had led him to believe.

THE IRISH CONVENTION

Londonderry was the honorary secretary of the UUC delegation sent to the Irish Convention. Meeting between July 1917 and April 1918, it was billed as an opportunity for ‘Irishmen on Irish soil’ to hammer out a constitutional settlement. In August Londonderry opened for the Ulster unionists. He claimed that they had come in ‘friendliness’ and with an ‘open mind’ to reach ‘some general kind of agreement of what is the best for the government of this country’. They believed that Ulster’s economic prosperity was attributable to the Union and the empire, and they viewed the British Isles as a common unity. He added, however, that unionists could be ‘won if they can be persuaded that self-government is better than the Union’. In private, he wrote afterwards to his mother: ‘We could govern Ireland from Belfast but I am not sure the stalwarts want to do that; they would much prefer to remain behind a six county [border] and make faces at the rest of Ireland’.

In an effort to inject momentum into the Convention, nine delegates, representing nationalism and unionism, agreed to form a subcommittee to discuss a hypothetical Irish parliament. Progress was made on its composition: an appointed upper house and a lower house with 40% of seats allocated to unionists. Representation at Westminster would continue. The subcommittee stumbled over fiscal powers, however. Nationalist members expected that an Irish parliament would control customs and excise, but the Ulster unionists feared that this would be detrimental to their province’s economic interests. In a last-ditch attempt to salvage its initial progress, Londonderry offered to propose a federal United Kingdom but he was dissuaded by other Ulster unionists, and federalism would not in any case have addressed the nationalists’ demand for fiscal autonomy.

The resulting stalemate reflected the delegates’ concerns about their political credibility beyond the Convention. Nationalists could not help but be aware of the challenge posed by Sinn Féin, and Ulster unionist delegates knew that retreating from partition risked creating further divisions in the UUC. ‘The Leadership of Ulster is not altogether a comfortable position’, Londonderry wrote to his mother in January 1918. ‘I think the Ulster men have a great opportunity, but I do not think they are going to take it.’ A fortnight later he lamented to his wife that ‘not even to win the war is a single concession going to be made … the rest of Ireland can go to blazes … Belfast always disheartens me … and the hatred of Ireland is a thing I really resent.’

NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE BOUNDARY COMMISSION

Londonderry was appointed minister for education and leader of the senate in Sir James Craig’s first government of Northern Ireland. The prime minister was aware of his minister’s reputation as a moderate. Writing in the Belfast News-Letter the year before, on Christmas Eve 1920, Londonderry had declared that the ‘setting up of two Parliaments gives the best chance of ultimate unity. Those acute points of difference may disappear in the discharge of duties common to the whole of Ireland … I do venture to hope that every Irishman, whether he be of the North or of the South, will … give his wholehearted co-operation towards achieving success.’ Similarly, in December 1921, in his remarks to the House of Lords on the Anglo-Irish treaty, Londonderry commented that the Dáil only needed to prove itself worthy for the Ulster unionists to consider participating in it, as they had ‘never expressed a determination to remain outside for all time’.

Given controversy in our own time about the alternatives of a hard border and an Irish Sea border, it is noteworthy that Londonderry signalled his preference for the latter when addressing the House of Lords in February 1923. Claiming on that occasion ‘to speak for the whole of Ireland’ on the restrictions imposed on Irish cattle imported to Great Britain arising from an outbreak of foot and mouth disease, he reasoned that these could not be relaxed only for cattle from Northern Ireland, as this ‘would mean the establishment of a strict surveillance of the frontier between Northern and Southern Ireland, and entail great expense’.

The 1921 treaty provided for a Boundary Commission to adjust the border, but in 1924 the Northern Ireland government threw a spanner in the works by refusing to appoint its commissioner. In public Londonderry defended partition. The ‘great clash between North and South was not some petty idiosyncrasy of the Ulsterman as opposed to that of an inhabitant of the South of Ireland’, he informed the Ulster Association in London. ‘It was the clash of ideals. Ulster would never agree with the South as long as the latter were looking at themselves and considering their own grievances and difficulties while Ulstermen were thinking of the Empire and keeping their eyes fixed on the Imperial ideal.’ Speaking shortly afterwards to the North Down Unionist Association, he referred to the southern government’s ‘grudging acceptance of the Imperial idea. So long as the South was actuated by those motives, it was no use for them to suggest any union with the North.’ Invoking the empire allowed Londonderry to sidestep his private concerns about the parochialism of Northern Ireland by casting Irish nationalism as insular.

Londonderry was nevertheless inclined to support the nomination of a boundary commissioner. A significant factor was the possible constitutional crisis that would flow from the Conservative-controlled House of Lords expressing its support for Craig’s unyielding position, in defiance of the Labour government. The deputy cabinet secretary, Thomas Jones, noted in his diary in August 1924 that Londonderry—then deputising for Craig at inter-governmental negotiations in London—was ‘the only reasonable negotiator’, but ‘too weak to bring along the rest of his party’. Shortly afterwards, Londonderry received a delegation of Conservative and Unionist MPs at his Mayfair home. His visitors made it clear that he had to stick to Craig’s cry of ‘not an inch’, and he was subsequently obliged to issue public assurances that he had not made any agreement behind Craig’s back. This, however, did not prevent Londonderry from working behind the scenes with allies in the Lords to avoid a showdown with the Commons, and as a result help pave the way for the British government to appoint Northern Ireland’s commissioner.

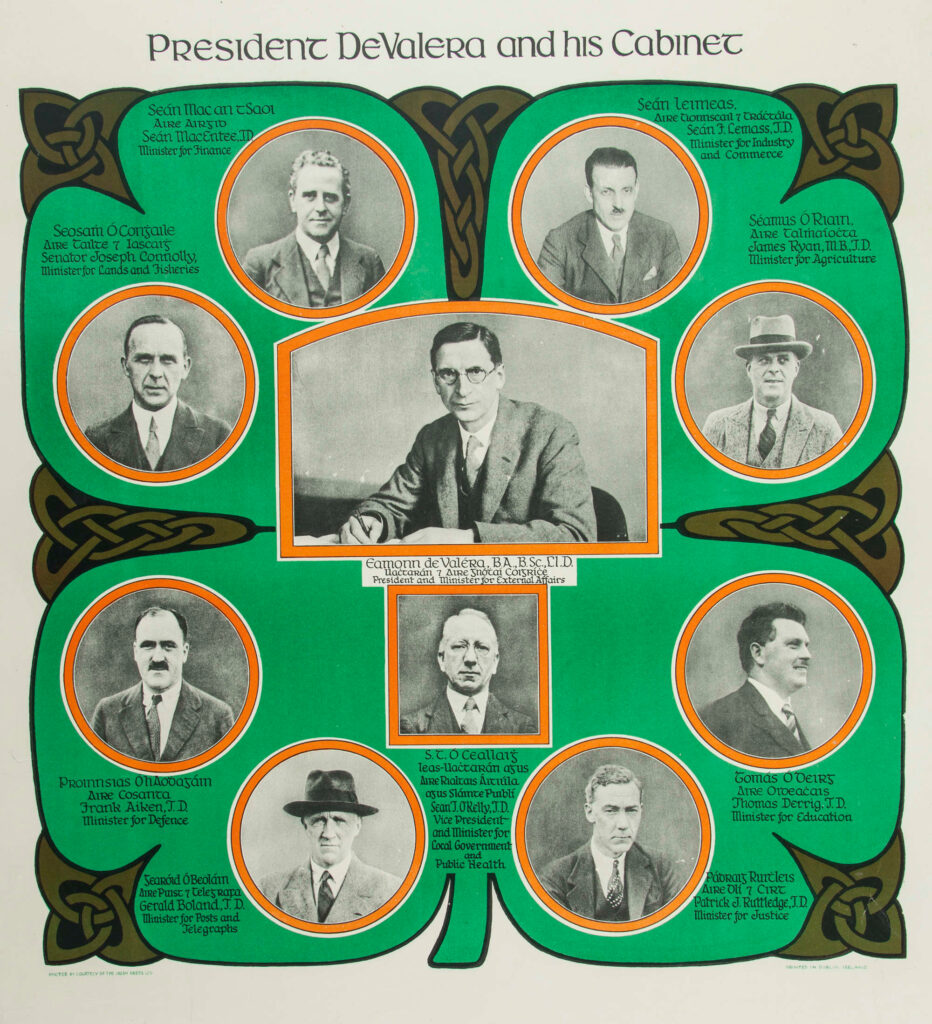

FIANNA FÁIL

The contrast that Londonderry made between north and south sharpened after Fianna Fáil took office in 1932. Éamon de Valera’s government put into practice the sort of anti-British and anti-imperial ideals that Londonderry regarded as irreconcilable with his sense of unionism. As a British cabinet minister in the early 1930s, he tried to discourage his colleagues from discussing the border with their Dublin counterparts. He maintained the posture after leaving office in 1935, most notably when the question of partition re-emerged during the Second World War as part of British efforts to secure the co-operation of the Irish government. His stance at this juncture is all the more noteworthy, given that several other Ulster aristocrats were now open to the possibility of unification if it helped the war effort, applying a rationale that Londonderry had once articulated, albeit in private, during the First World War.

The imperial, British and Irish aspects of Londonderry’s sense of national identity together shaped his views and actions about the partition of Ireland. The first was ill defined, though it encompassed support for Indian self-government. In the context of Irish affairs, it often boiled down to supporting Great Britain as a world power. His British identity was reflexive, a product of his aristocratic roots in Scotland, England and Wales. Londonderry’s Irishness was sincerely felt, but it recoiled from expressions of national identity that rejected Britishness and the ‘imperial ideal’. As a result, his receptiveness to an all-Ireland constitutional settlement was greater when nationalism appeared to be similarly supple in response to unionism, as was fleetingly the case at the Irish Convention. Correspondingly, the constitutional and economic policies pursued by successive Fianna Fáil governments in the 1930s and 1940s rendered him consistently hostile to any steps that undermined the integrity of Northern Ireland.

In the final analysis, Londonderry believed that the achievement of an all-Ireland settlement could not be secured by nationalists winning over some open-minded Ulster unionists but rather through finding an effective and practical constitutional arrangement that reconciled nationalism and unionism. ‘There would be nothing easier’, he informed Lady Fingall in November 1917, ‘than … by means of a few phrases to gain thunderous applause from a number of very ignorant men. Suppose I had reason to suddenly change my views … those amongst whom I live are of totally different material. And after all, what is the gist of your argument, that we are so stupid or so avaricious that we will not subscribe to the Sinn Féin programme?’

N.C. Fleming is Professor of Modern History, University of Worcester, and author of The Marquess of Londonderry (revised edition, London, 2024).

Further reading

N.C. Fleming, Aristocracy, democracy, and dictatorship: the political papers of the seventh Marquess of Londonderry (Cambridge, 2022).

N.C. Fleming & J.H. Murphy (eds), Ireland and partition: context and consequences (Clemson, 2021).

C. O’Halloran, Partition and the limits of Irish nationalism: an ideology under stress (Dublin, 1987).

A. Parkinson & B.M. Walker (eds), Ulster 1912–22: change, controversy, conflict (Belfast, 2024).