By Niall Whelehan

In 1888 the International Council of Women was founded at a conference in Washington DC that brought together over 50 organisations from nine countries. Present were the acclaimed feminists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, as well as Marguerite Moore, the only Irish delegate there. Addressing the convention, Moore described how, through the Ladies’ Land League, ‘we Irish women have already taken our place in the political van. When our brothers were imprisoned we stepped forward and carried on the work.’ Four years earlier Moore had emigrated to New York, where she became known as a leading feminist, labour reformer and Irish nationalist. She linked her campaigning for women’s rights at the turn of the twentieth century to her activities in the Ladies’ Land League, which had led to her imprisonment for three months in Tullamore in 1882. Later, during the revolutionary era, she provided a direct link between the Ladies’ Land League and the new Cumann na mBan generation in the United States.

The history of the Ladies’ Land League, which represented a marked advance in women’s involvement in Irish land reform and nationalism, is most often told from the perspective of its leader, Anna Parnell. The overlooked figure of Marguerite Moore presents a different view. The Ladies’ Land League came to an abrupt halt in August 1882 amidst exasperation with male leaders and acrimonious division between Anna and her brother, the Land League president Charles Stewart Parnell. Moore’s life, however, illustrates how some of the radical alliances forged in the organisation during the Land War proved resilient. In the aftermath of the Land War, feminism moved to the centre of her activism, though it was combined with nationalism rather than being in tension with it. This nationalism was sometimes colourfully expressed: Moore owned a pet parrot that greeted visitors to her New York home by squawking ‘God Save Ireland’ and ‘Erin go bragh’.

THE LADIES’ LAND LEAGUE

Marguerite Moore was born in Waterford in 1846 and was orphaned at the age of eleven. An inheritance provided for a convent school education in Tipperary, where one of her classmates was Mary Jane Irwin, the future wife of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. Moore married young and moved with her husband to Moville, Co. Donegal. The Land League had a strong presence on the Inishowen Peninsula and the Ladies’ Land League quickly took root there. The Moville branch was among the first in Ireland when it started in January 1881, with Moore and at least 50 other members. In May, Anna Parnell came to a demonstration in Moville and met with Moore, persuading her to take on a national role as a travelling organiser.

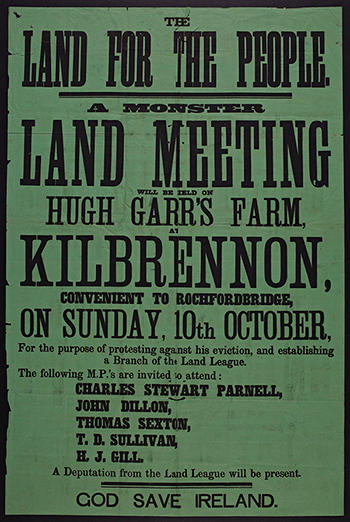

In 1881–2 Moore travelled across Ireland, organising branches, distributing relief and encouraging resistance to evictions. She quickly earned a reputation as an eloquent speaker who regularly used humour to win over audiences and to ridicule the RIC men present at her talks. Her organising also extended beyond Ireland. She made several trips across the Irish Sea and played an important role in linking emigrant branches in Scotland and England with the Ladies’ Land League in Ireland. She addressed rallies in Glasgow, Dundee, Birmingham, Durham, Darlington and Jarrow, amongst other cities, sometimes sharing the platform with British reformers and trade unionists. She told her audiences that the organisation was called ‘the Ladies’ Land League for the sake of euphony, but it was women they wanted, not ladies’. Her tours were well received. When imprisonment in Ireland prevented her from attending a rally in Dundee in 1882, an enthusiastic crowd, comprised mainly of working-class emigrant Irishwomen, gathered in the city centre to hear the Land Leaguer John Ferguson read out a letter that Moore had sent from her jail cell.

HENRY GEORGE

During the Land War Moore met the internationally acclaimed economist Henry George and his wife, Annie Corsina Fox, and considered him ‘the greatest political economist of his day’. In 1881 George arrived from the United States to radicalise the Land War and advance his version of the land nationalisation doctrine, whereby people would pay a rent or tax to the State to occupy land but could not own it as private property. The Irish land question was no ‘mere local question’, George proclaimed, ‘it is a universal question. It involves the great problem of the distribution of wealth, which is everywhere forcing itself upon attention.’ George worked closely with the Ladies’ Land League, which had been directing the agitation since the imprisonment of many male leaders in October 1881. Moore shared platforms with several George allies in Ireland and Scotland, including Edward McHugh, Ellen Quigley and Harold Rylett. In May 1882 the Land League leaders were released from prison and they contrived to shut down the Ladies’ Land League, partly because they viewed it as a more radical organisation. Throughout this period George’s column in the New York-based Irish World offered support to the women and criticised Charles Stewart Parnell’s new direction.

During the Land War Moore met the internationally acclaimed economist Henry George and his wife, Annie Corsina Fox, and considered him ‘the greatest political economist of his day’. In 1881 George arrived from the United States to radicalise the Land War and advance his version of the land nationalisation doctrine, whereby people would pay a rent or tax to the State to occupy land but could not own it as private property. The Irish land question was no ‘mere local question’, George proclaimed, ‘it is a universal question. It involves the great problem of the distribution of wealth, which is everywhere forcing itself upon attention.’ George worked closely with the Ladies’ Land League, which had been directing the agitation since the imprisonment of many male leaders in October 1881. Moore shared platforms with several George allies in Ireland and Scotland, including Edward McHugh, Ellen Quigley and Harold Rylett. In May 1882 the Land League leaders were released from prison and they contrived to shut down the Ladies’ Land League, partly because they viewed it as a more radical organisation. Throughout this period George’s column in the New York-based Irish World offered support to the women and criticised Charles Stewart Parnell’s new direction.

Despite giving the odd public lecture, Moore became a peripheral figure after the demise of the Ladies’ Land League. She became a widow in this period, and her eleven-year-old daughter Lelia also died. In 1884 Moore sailed to New York with her remaining children. Perhaps family tragedy contributed to a desire for a fresh start, but it seems likely that opportunities to continue activism in social and political reform were pull factors. In New York, Moore could maintain her links with Henry and Annie George. In 1884 George returned to Ireland for a short visit, and shipping records show that Moore sailed for New York by the same route just one week after his departure from Queenstown that April.

Moore quickly became a familiar face at Irish political and cultural events on the east coast of the United States. She participated in a range of causes and campaigns, including Henry George’s 1886 run for New York mayor, the Women’s Single Tax Club, the United Labor Party, the Irish National League, the Universal Peace Union, and the radical priest Edward McGlynn’s Anti-Poverty Society. It was for her involvement in women’s rights organisations, however, that Moore became most widely known, with one New York newspaper describing her as one of four ‘leaders in the movement that is making this the woman’s age’.

When the Ladies’ Land League first started, Fanny Parnell maintained that it was not a women’s rights organisation, yet there was a clear crossover. Just weeks after her initial call to arms in the Irish World in 1880, a front-page article in the same newspaper contended that ‘women are entitled to equal political rights with men, to equal rights to common property, to equal rights with men to the inheritance left by parents’. From the mid-1880s Moore contributed articles to the Woman’s Journal and spoke extensively on voting rights in eastern American cities, addressing meetings of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association, often sharing a platform with the prominent campaigner Lillie Devereux Blake. In 1894 Moore told a rally that ‘equal rights, not women’s rights, are what we want—the right to equal wages for equal work, equal right to own property and equal right to our children’. Her activism also took on internationalist dimensions and she attended the first convention of the International Council of Women, telling fellow delegates that ‘I stand here as a representative of Irish women … having received the highest honor in the power of the English government to bestow upon an Irish woman, that of imprisonment for the love of her country’.

ACTIVISM MAINTAINED

Despite the frustrations wrought by the end of the Ladies’ Land League, Moore remained active in nationalist circles and was a committee member of the Charles Stewart Parnell branch of the Irish National League of America. Following the 1890 split in the Home Rule party she remained a Parnellite. At the same time, she held personal links to more militant nationalists. In New York she was reunited with her former schoolmate, Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa, whose husband was one of the instigators of the dynamite campaign in British cities in the 1880s. They remained friends, and in 1916 Moore delivered the eulogy at the memorial following the other woman’s death. In 1914–15 Moore addressed rallies in New York with Francis Sheehy-Skeffington and with Gertrude B. Kelly, and openly compared the new generation of activists with the Ladies’ Land League of over 30 years earlier. She helped raise funds for the families of the 1916 rebels and in 1920, aged 74, she played a role in the American Women Pickets, a group of nationalists and suffragists who staged provocative protests at the British embassy in Washington.

After the War of Independence Moore faded from public view, and she died in 1933. Emigration had facilitated the development of her multifaceted activism and prominence as a women’s right campaigner. Yet her blend of feminism, nationalism and Georgism first took shape in the Ladies’ Land League in Ireland and through her encounters with Henry George and Anna Parnell rather than being simply a product of the United States. While the Ladies’ Land League came to an untimely end in 1882, Moore’s life reveals how the organisation generated progressive alliances that were sustained in the decades after the Land War.

Niall Whelehan lectures in history at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, and is the author of Changing land: diaspora activism and the Irish Land War (New York University Press, 2021).

Further reading

E.L. Hodges, ‘A transatlantic profile of Marguerite Moore’, New York Irish History 32 (2018).

T.M. McCarthy, Respectability and reform: Irish American women’s activism, 1880–1920 (Syracuse, 2018).