Jim Blaney

The ballad known as McCafferty or McCaffery has long been a favourite. It was said to have been so popular that it was banned in the British army, since it appeared to authorities to be altogether too sympathetic to Private Patrick McCaffery, who had been executed for shooting two of his superior officers.

When I was scarcely eighteen years of age,

Into the army I did engage,

I left my house with full intent

To join the forty-second [sic] regiment;

To Fulwood barracks I then did go

To do some duty in that old depot,

But out of trouble I never was free,

For my captain took a dislike to me.

As I was posted on guard one day

Some soldiers’ children came out to play,

From the officers’ quarters my captain came

And he ordered me to take the parents’ names.

I took one name just out of three,

For neglect of duty he then charged me,

To the orderly room the next morning I did appear,

But my sad story he refused to hear.

With a loaded rifle I did prepare

To shoot my captain on the barrack square,

It was my captain I meant to kill,

But I shot my colonel against my will;

I shot my colonel I shed the blood,

At Liverpool assizes my trial I stood,

Says the judge to me, ‘McCafferty,

Prepare yourself for the gallows tree’.

I have no mother to break her heart,

Nor yet a father to take my part,

But I have one and a girl is she,

Would lay down her life for McCafferty.

All you young officers take warning by me,

And treat your men with some decency,

But all you people who pass this way,

Say ‘May the Lord have mercy on McCafferty’.

____________________

(Lyrics from the late Patrick Loughran, Lurgan,

County Armagh)

Some music critics have denigrated this fine composition by relegating it to the realms of fiction, one asserting that ‘no-one died and McCaffery wasn’t hanged’ (Dominic Behan), another suggesting that it ‘was probably a figment of a bored soldier’s imagination and not based on fact’ (Bill Meek). In fact the anonymous songwriter was remarkably accurate in his chronicle of events.

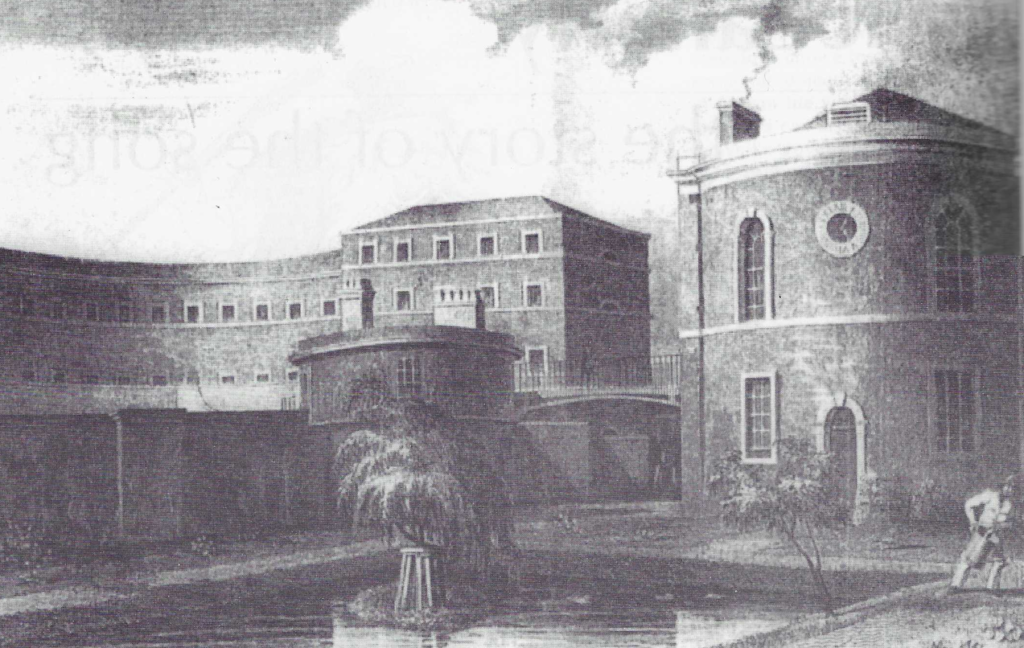

At Fulwood barracks near Preston, about eleven o’clock on Saturday morning 14 September 1861, Private Patrick McCaffery was taken before Colonel Crofton and Adjutant Hanham. After being charged with neglect of duty he was sentenced to be confined to barracks for fourteen days. Soon afterwards the colonel and adjutant were walking together in the barrack square, and McCaffery seeing them from his room, took down his rifle (an Enfield no.106), went into the square, kneeled down on one knee, took aim at Hanham and fired from a distance of some sixty to sixty-five yards. The ball however struck Colonel Crofton on the right side, passing through his left lung before striking Adjutant Hanham’s left arm and lodging in the lower part of his thigh. Hanham managed to walk to his room unassisted, but Crofton had to be helped to his quarters by shocked comrades. The victims were immediately attended by Doctors Clarke and Donald of the barracks and Dr Hammond of Preston.

‘I meant it for the captain’

McCaffery, who had returned to his room after the shooting, was at once lodged in the refractory cell, his shoes and braces were removed and his hands were fettered. Captain Elgee, chief of the county constabulary and superintendent Robert Green were sent for, and the prisoner was taken into custody and removed to the Preston House of Correction. In the course of interrogation McCaffery stated: ‘I did not intend to murder them’, and later added ‘I did not intend to shoot the colonel, I meant it for the captain, however it does not matter much’.

Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Dennis Crofton, aged forty-seven, expired at 10.15 on Sunday night 15 September. Adjutant and Captain John Hanham died the following morning at 11.15. The colonel had served with distinction in the Crimea (1854-55), where he was severely wounded at the battle of Inkermann. He was honourably mentioned in dispatches, and his decorations included the French Order of the Legion of Honour and the Sultan’s Fifth Cross of the Mejidie. He left a wife and three young children. Captain Hanham was wounded at the battle of Moodkee during the Sutlej campaign (1845-46), and had displayed great bravery at Kabul. He left a wife and four very young children. The inquest into the tragedy took place at the House of Correction (Kirkdale County Jail), on Monday and Tuesday, when a number of witnesses were called to give evidence. At the conclusion of the evidence the jury retired for two or three minutes and returned with a verdict of ‘wilful murder’ against Patrick McCaffery. The coroner then made out a warrant for his committal to the next Lancashire assizes.

Newspaper speculation

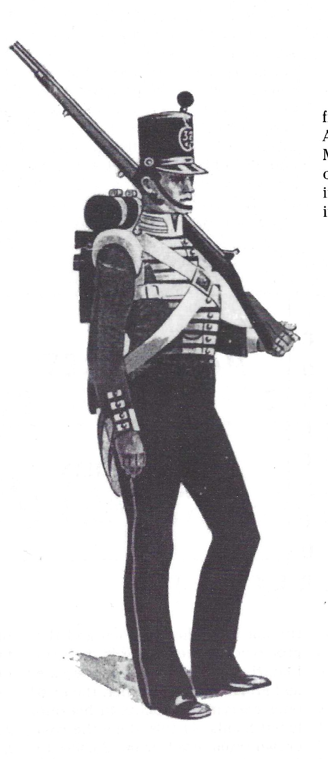

McCaffery, who was described as being of fair complexion and short in stature, had only joined the 32nd Regiment (Lucknow Heroes) the previous October (1860), and although his age was given as nineteen, he was, according to the census taken on 7 April 1861, aged eighteen. The newspapers took a great interest in his career, vying with each other to supply information on his background and family history. He was variously described as ‘the wretch’, ‘the assassin McCaffery’, etc. and readers were informed that ‘he bears a very bad character for drunkenness and insubordination’, and that ‘he has not borne the best character while in the regiment, his father also was transported a few years since for being concerned in a poaching affray’. It was claimed that he had been in the cells before. Most newspapers declared him to be a native of Preston, some allowed that he was an Irishman, one informant however, said to be an acquaintance of McCaffery, stated that

contrary to newspaper reports, he was not a native of Preston, although probably entered the regimental books as such, but was born in the neighbourhood of Aughnacloy, County Tyrone. From thence the family moved to Belfast where they resided for two or three years, the father working as a dock labourer, before moving to England. He has still relatives in Belfast employed as mill workers. McCaffery is a Roman Catholic.

The south Lancashire assizes were held on Thursday 12 December 1861, before Mr Baron Channel. The court was already crowded to excess when his lordship took his seat at 10am. Patrick McCaffery was then placed at the bar and formally charged with murder. He was dressed in the uniform of the 32nd Regiment and looked the picture of innocent youth. His regiment shared Fulwood barracks with five others under the command of Colonel Crofton, with Captain Hanham as his adjutant.

Harsh realities of army life

Evidence was given by many witnesses, including comrades of the prisoner. From these we learn something of the harsh realities of life in an army barracks, and the background to the tragedy. On Friday 13 September 1861 Patrick McCaffery was picket sentry near the officers’ quarters, who were being annoyed by noisy barrack children playing outside their quarters. Captain Hanham came out and ordered McCaffery to get the names of their parents. He returned with the name of only one. Captain Hanham then ordered him to the guard room and there he remained till the following morning when he was brought before Colonel Crofton and Hanham and charged with neglect of duty and of not obeying an order. The colonel asked the prisoner what he had to say and he replied, ‘I did my best, the children ran away, and I could only get the name of one of the parents’. He was then confined to barracks for fourteen days, with the further punishment of pack drill, with his knapsack on his shoulders. Then one of the sergeants took him around the other sentries, in order that he would not be able to pass out of the gates (this was done as much for the disgrace as for the punishment). He was then set at ‘liberty’. It was some time after this that he went to his room, took out his rifle, and prepared to shoot Captain Hanham.

The trial lasted until about 4pm. Mr Russell for the defence asked the jury to look at the circumstances:

a lad scarce emerged from childhood, and considering the awful feeling which must have since occupied his mind, he was more to pitied than dispised. Unjust treatment he had received at the hands of Captain Hanham, and that for a simple offence the prisoner had been placed under arrest, had passed a sleepless night and been subjected to the degradation of confinement to barracks. Smarting under the indignity of the disgrace of imprisonment in the guard room by the orders of Captain Hanham was it unnatural of him to take revenge for the harsh treatment of his officer?

The judge’s summing up was decidedly against the prisoner. The jury retired to consider its verdict and the prisoner was removed to one of the cells below. Ten minutes later the jury re-entered the court and the prisoner was brought back into the dock. The clerk of the court put the usual question and the foreman announced a verdict of wilful murder. The judge then assumed the black cap and passed sentence of death on the prisoner:

Patrick McCaffery, a jury of your country has found you guilty upon this indictment of the charge of wilful murder, and in that verdict I entirely concur. It has been said that you had been smarting under provocation from what you considered unjust punishment, but no such complaint on your part can justify the acts of violence to which you resorted…I earnestly implore you, indulge in no belief that your life will be spared. I pronounce upon sentence according to the law, that you be taken from hence to the place from which you came, thence to the place of execution, and that you be there hanged by the neck until you be dead, and that your body be buried within the precincts of the prison in which you were last confined, and may God have mercy on your soul.

The date of the execution was fixed for Saturday 11 January 1862. A private letter written by one of McCaffery’s comrades on the day of the shooting gives an interesting insight into the background of the incident:

McCaffery had been up before the colonel two or three times lately for very trivial things, and has been occasionally confined to barracks. A short time ago they gave him seven days in cells, and all his hair was cut off his head. Yesterday he was on picket—that is on duty in the barracks to keep people away from the officers’ quarters. During the afternoon some children belonging to the soldiers of the battalion to which he belongs were playing near the officers’ mess, when the adjutant came up and asked him why he allowed the children to play there. In reply he said he had no orders against their being allowed to do so. The adjutant then ordered him to get the names of the parents of the children. The youngsters however, ran away and he could only get the name of one of them. As soon as he told the adjutant that he could only obtain one name, the adjutant had him placed in the guard room. There he was kept all night, and this morning he was brought before the colonel, who gave him fourteen days confinement to barracks. This seems to have exasperated him to such an extent that he determined on taking revenge for being confined for so simple an offence.

On 6 January, a few days before his execution, McCaffery wrote two letters from Kirkdale Jail, one to a comrade, the other to his sergeant, McLernon:

You see the end I have come to; and whose fault is it but my own? How many times have I thought on the advice you proffered me so often, and rejected with contempt. Ah yes, I see it now, but it is too late to profit by it. However, I know you will be pleased with me for asking your forgiveness, which I know you will freely grant me. Friend, I am sorry for what I have done, and the misery I have caused. You might wish to know how I feel now, and what my thoughts are. My thoughts are now wholly occupied with God. I hope Him who died for us on the cross will be merciful to me when my mortal life is no more. Friend, pray for me that God may pardon my sins. My execution will take place on 11 January, Saturday next.

I am yours,

Patrick McCaffery.

Preparations for the execution began on Friday the 10th. A platform was erected against the jail wall about eighteen feet from the ground and close to the cell of the condemned man. This was covered in front with black cloth about four feet long. Inside the platform standing on an iron railing was the gallows. On Friday evening there were various rumours going around—that a reprieve was likely owing to the extreme youth of the prisoner, of his great penitence, and of the sympathy of his colleagues. He retired to rest that night at 11pm and slept soundly. He rose at 5am and from there until the arrival of the Revd. H. Gibson and Fr Lanns at 7am he was engaged in prayer. After receiving the Holy Sacrament he had his breakfast around 8am.

Like a fair day

From an early hour incessant rain had been falling. At 10am 200 Liverpool police arrived to do duty at the scene of execution. From 10.30 the crowd began to increase rapidly, consisting chiefly of young men and many women, some with children in their arms. Remarks heard in the crowd suggested a lot of sympathy for the prisoner: ‘It’s a pity to hang him’, said one’; ‘they persecuted the poor fellow enough before he did it’, said another; ‘they drove him to it’, etc.. Around 11am a large crowd arrived by train from the manufacturing districts and from then on every thoroughfare was densely thronged with people heading towards the place of execution. By 11.30 the area around the jail resembled a market or fair day, though by now the rain was pouring down in torrents. All available vantage points were occupied, and on one side of Whitehead Lane there were about 200 cabs, carts and other vehicles, which had brought their occupants from nearly all parts of Liverpool.

At a quarter to twelve the under sheriff and the governor and other officials of the jail arrived at the condemned cell and the process of pinioning began. When McCaffery was informed that his time had nearly expired he thanked the governor, Captain Gibbs, and the two priests for their kindness, and gave himself up to the executioner Calcraft. At ten minutes to twelve the iron doors of the jail were thrown open and the procession moved towards the scaffold, the Revd. Gibson on one side and Fr. Lanns on the other, the prisoner carrying a crucifix in his pinioned hands. At this stage the vast crowd numbered from 25,000 to 30,000. The turnout was about equal to that which witnessed the execution of Gallagher the shoemaker, who murdered his wife about twelve months before.

Resigned to his fate

Revd Gibson read the prayers according to the rite of the Catholic Church, entitled ‘The recommendation of a Departing Soul’. The prisoner came to the front of the platform and gazed into the crowd. His physical appearance had deteriorated since his trial, his face was exceedingly pale and he seemed to be suffering from intense mental agony, but managed eventually to compose himself and appear resigned to his fate. As he emerged from the doorway, he was followed by Calcraft the hangman and then by Fr. Lanns. He was dressed in prison garb (a grey jacket and trousers) and he replied to the priests’ prayers with ‘Jesus have mercy on my soul’. His mild countenance and boyish appearance elicited the greatest sympathy from the vast crowd. Calcraft then came forward and placed the white cap on the condemned man’s head and put the rope around his neck, and after a short delay he attached the hook at the end of the rope to the chain above. McCaffery expressed a wish to address the crowd, but his request was denied. He had been so tightly pinioned that his hands had turned a purple colour. Calcraft went below, and after a longer than usual delay withdrew the bolt. Shrieks came from the crowd. There was the noise of a jerk and the grating of the chain, and the body fell heavily. After a moment the limbs began to shake but after about forty seconds all was stilled for ever. Several of the females in the crowd left weeping. Many were the prayers offered up by the sympathetic crowd, such as ‘God help him’, ‘God bless him’, and ‘Lord have mercy on him’. After an hour hanging on the scaffold the body was cut down, and during the afternoon was interred within the precincts of the jail. Calcraft completed his task amidst yells, hisses and maledictions from the crowd. Thus ended the young life of Patrick McCaffery.

Jim Blaney is a local historian from Lurgan, County Armagh.

Further reading:

L. Snell, A Short History of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry 1702-1945 (Aldershot 1945).

H. Shimmin, ‘At a private execution [in Kirkdale Gaol], in Porcupine, vol.II (1870).