By David Burke

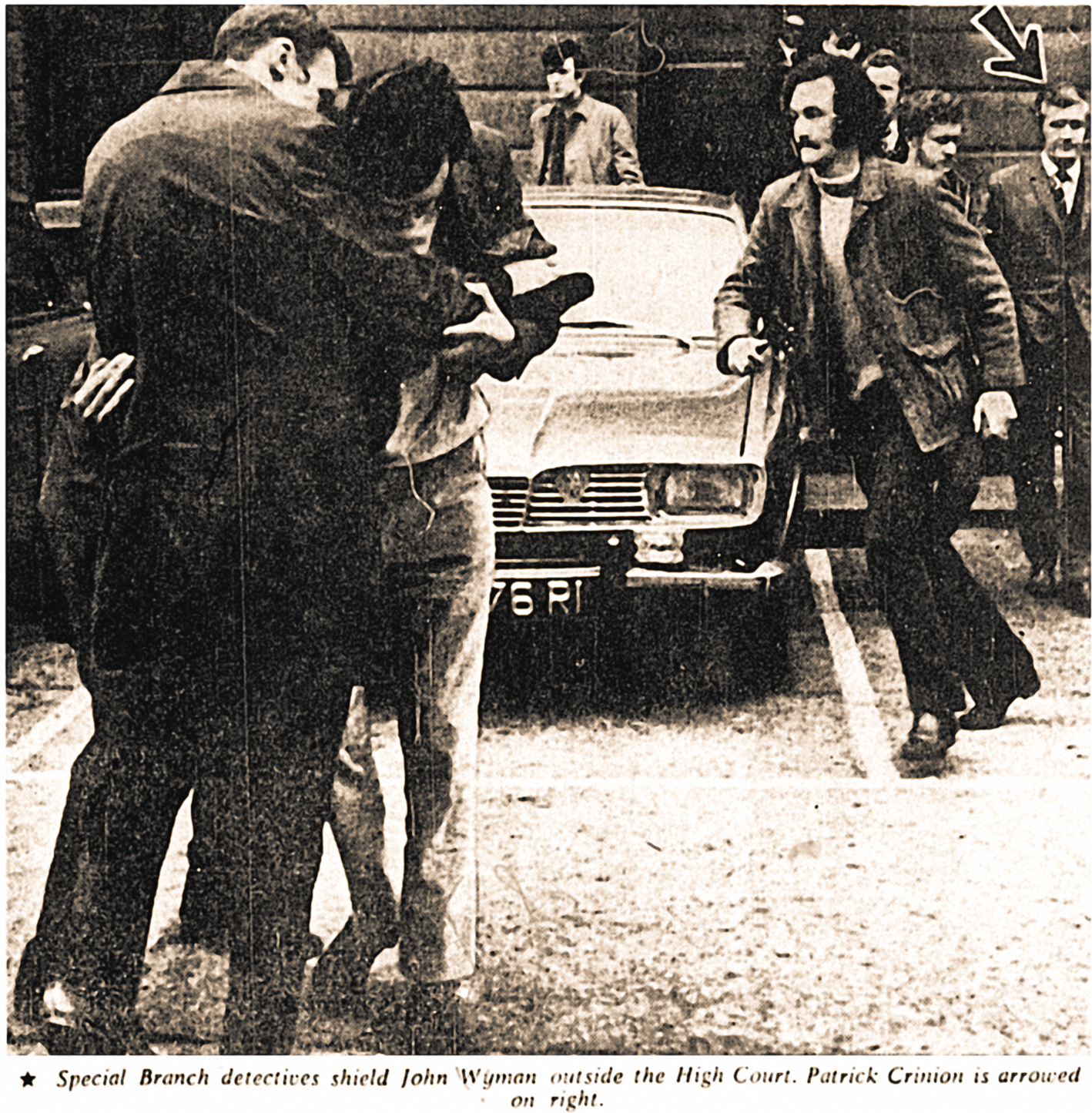

Previously in History Ireland (HI 26.3, May/June 2018) Margaret Urwin and Niall Meehan re-examined the case of Patrick Crinnion, a senior Garda intelligence officer who, for over a decade, betrayed Garda security secrets to Britain’s MI6. The article provided convincing evidence that a man called Alex Forsey was part of a network of British spies in the Republic of Ireland. The web was overseen by MI6 officer John Wyman, who ran both Forsey and Crinnion, as well as English agents provocateurs bank robbers Kenneth and Keith Littlejohn. Urwin and Meehan described how Forsey’s arrest led first to Wyman and then Crinnion in December 1972.

I published The puppet masters, on the Crinnion–Wyman scandal, in June 2024. A benefit of getting a book on the shelves is that untapped sources can often subsequently emerge in response. Recently I was given a handwritten letter, quoted at length below, written by a retired senior official. Although he has since passed away, he must remain anonymous. I will call him the ‘commentator’. He was directly involved in events that took place during Crinnion’s and Wyman’s Mountjoy Prison incarceration.

CRINNION AND WYMAN

Over the period 1972–3 Crinnion and Wyman were held in Mountjoy Prison. A Department of Justice (DoJ) instruction prohibiting communication was undermined, according to the ‘commentator’. ‘Contrived lavatory visits’ were ‘combined with staff failure in allowing [them] to coincide’. Cell doors were not routinely locked. As a result, it ‘gave opportunity to both prisoners to flick notes, on small scraps of paper, into each other’s cells’. They were discovered after a search and confirm Urwin’s and Meehan’s view of Forsey as a British spy. News of the notes was relayed to the DoJ. A further search revealed that Crinnion’s food tray hid more information:

‘It was an ordinarily sized, brown, laminated, wooden, tray, pressed mechanically into its shape. [Crinnion] had a folio sized sheet of silver foil, folded to conform to the size of the tray, in the depression uppermost on the tray, as a sort of “tray-cloth”.’

Inside were revealed ‘several sheets of A4 sized stationery’ with a ‘closely written on both sides of every leaf, lengthy, letter’, running to four or five leaves, ‘addressed to An Taoiseach’ (then Jack Lynch).

THE EARL OF GRANARD

The puppet masters ventured that Crinnion’s deferential Ascendancy attitudes stemmed from his mother’s role as housemaid at Powerscourt House, Co. Wicklow, and from their residing in an estate cottage on the Boghall Road, Bray. In his Mountjoy letter, Crinnion reportedly revealed that he also spent a formative part of his youth in County Longford, working on the Earl of Granard’s Castleforbes estate. The ‘commentator’ went on to describe how

‘… [Crinnion’s] father seemed to have been absent from his childhood. Nuancing indicated an ingrained “tenantry” obeisance to the Earl. There was acknowledgement of kindness by the Earl to the family. It was also clear that the [Earl had] British rather than Irish propensities …’

Crinnion was bright; he later joined Mensa. This was noted by co-workers. One of the ‘estate people’ made ‘a personal approach to the Earl when Crinnion was in early adulthood’. This, said the ‘commentator’,

‘… resulted in [Crinnion] going to England, either to join, or be—in some unrecollected way—“familiarised” with policing. Without any great lapse of time, advised, I think, either directly, or indirectly by the Earl, Crinnion returned to Ireland, to join An Taca Síochána [the part-time garda reserve], from which he ultimately joined An Garda Síochána.

It was conveyed to Crinnion; either when he was associated, in whatever way he was, with policing in England; or when he later joined An Taca Síochána; whether directly or indirectly by the Earl, or by somebody else. I cannot recall at all; that he should respond cooperatively, when, one day, he would be “approached” career-wise.’

Crinnion became, in other words, a ‘sleeper-agent’, awaiting activation.

Arthur Forbes, the Earl of Granard (1915–92), was UK air attaché to Romania at the start of the Second World War. He spirited diplomats and politicians escaping newly occupied Poland from Romania to Greece via Bucharest on his Percival Q6 aircraft. The following year, he was deputy air attaché to Greece. Later again, his insights were sought as an adviser to Britain’s minister of state for the Middle East. The Earl presumably had, and possibly retained, a relationship with one or more British intelligence agencies.

A CLANDESTINE MEETING WITH THE SECRETARY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

Having joined An Taca Síochána, Crinnion passed his Garda exams and, on 10 May 1955, joined the force proper. A legal action against the Garda Commissioner, while on the beat, was something that should ordinarily have stalled his career. Instead, he was quickly assigned to Dublin Castle’s Special Detective Unit (SDU).

While there, he reportedly received an extraordinary summons to a clandestine meeting with Thomas Coyne, DoJ secretary from 1949 to 1961. Born in 1901, Coyne joined the Royal Flying Corps during a politically significant year, 1918. The aviation community in Ireland at this time was small, suggesting that, if for no other reason, Coyne and the Earl of Granard may have known each other. As Coyne retired in February 1961 and Crinnion was sent to C3 (responsible for national security) at Garda HQ in the Phoenix Park around December 1960, the Coyne–Crinnion meeting probably took place at some stage towards the end of 1960.

The ‘commentator’s’ letter reveals that ‘Tommy Coyne’ asked Crinnion to come see him in the Department of Justice. There, he ‘received instructions from Coyne’:

‘He was informed that he was going to be assigned to duty, with whatever Garda Division it was that handled Security, in the Depot in Phoenix Park. He would start at the clerical bottom, inform himself, be efficient, become valued and maintain confidentiality about being seen by Mr Coyne. The Department of Justice did not want to hear from him. He might hear from the Department. If he did, the expectancy was that he would be appropriately productive and cooperative. [Crinnion] did not elaborate further in his letter.

[Crinnion] maintained, when interrogated [in 1972], that transactions, such as his with Wyman, were “ordinary” practice in the Garda. My recollection such as it is, tends to be that he was implying that what had happened came under the umbrella of his understanding with Mr Coyne. I clearly remember the shock his letter was to any of those in the Department who succeeded to the office or the functions of Mr Coyne, or who served with him. At that juncture, Mr Coyne was deceased and [Coyne’s successor] Mr [Peter] Berry retired.’

As The puppet masters explains, MI6 already had a C3 garda spy, the about-to-retire Thomas Mullen, who later admitted his role to Mick Hughes of the Special Detective Unit. Mullen justified his spying on the basis that ‘there has to be someone to forward information to Britain’. He also revealed that there had been another spy in C3 who had recruited him. In other words, there was an unbroken MI6 line in C3, at least since the Second World War.

FOLLOWING DOJ ORDERS

The ‘commentator’ said that the thrust of Crinnion’s approach in his letter to Jack Lynch

‘… was that personal investigation, by An Taoiseach, if sensitively conducted, person to person, at Commissioner level, would establish his bona-fides and would likewise establish that liaisons, such as his with Wyman, were known about and not excluded at the level at which he was operating, in a sector of mutual concern. Reassured, An Taoiseach could then facilitate appropriate disposal of his prosecution.’

The decision-making authority on Garda co-operation with foreign intelligence services resided then—as now—with the government, not the DoJ. Hence, while Lynch might have felt some sympathy for Crinnion—as a pawn in a larger game—it was unlikely that he would accept that Crinnion had acted legally.

More importantly, it should have been clear to Lynch that Crinnion could blow apart the case against former ministers Haughey and Blaney, and Captain Kelly, in the 1970 Arms Trial. By his own admission, as The puppet masters reveals, in concert with Wyman, Crinnion alerted opposition leader Liam Cosgrave in May 1970 to a seemingly illegal arms importation attempt. Though anonymous, that ‘garda note’ precipitated the Arms Crisis. The spy-pair were obsessed with portraying ministers Haughey and Blaney as IRA collaborators. They were successful.

DID COYNE HAVE AN ACCOMPLICE?

It is likely that Coyne, anxious to ensure continuity, had a DoJ accomplice. Recall that Coyne reportedly stated that the DoJ ‘did not want to hear from’ Crinnion although Crinnion ‘might hear from the Department’. Since Crinnion was to go to C3 and ‘start at the clerical bottom’, it was clearly envisaged that this process would take time. Coyne resigned shortly after talking to Crinnion, plausibly indicating that another DoJ official was in place to continue operations.

The ‘commentator’ knew Coyne’s successor, Peter Berry, DoJ assistant secretary in charge of state security up to 1961. He felt that the Crinnion affair should not exclude the ‘possible role of Peter Berry’. If Berry also knew of Crinnion, it further turns the 1970 Arms Crisis on its head. In 1970 Berry shared the Crinnion–Wyman view of Haughey and Blaney and communicated ‘evidence’ of illegal ministerial activity to Jack Lynch. He was dismayed by Lynch’s seeming indifference. Afterwards, Cosgrave received Crinnion’s anonymous garda note. Berry was in turn close to his 1971–86 successor, Andy Ward. Ward took no action on the prima facie case that Coyne had engaged covertly with Crinnion.

As best as I can tell, Assistant Garda Commissioner Ned Garvey, who oversaw C Division (which included C3), and Larry Wren, director of C3, did not ensure that Crinnion was debriefed. If they did, they buried it. After return to office in 1977, the Fianna Fáil government peremptorily, without explanation, dismissed Garvey, who had been promoted to Garda Commissioner in the interim. In 1979 Wren’s successor, Joe Ainsworth, discovered that C3 did not keep a file on the Crinnion affair.

The Crinnion–Wyman trial took place in February 1973. Minister for Justice Des O’Malley, a Jack Lynch ally, instructed that official documents that Crinnion allegedly intended to pass to Wyman be withheld. Consequently, the pair were convicted on lesser charges and released at the end of the trial. That same day Crinnion and Wyman flew from Dublin Airport to Birmingham on a private MI6 jet.

In The puppet masters I speculated that the chief of MI6, Sir Maurice Oldfield, had ‘other horses in the race’. I am now more convinced of that than ever. A copy of Crinnion’s Mountjoy letter was placed in the archive of the ‘Security’ department of the DoJ. Another should be with the Department of the Taoiseach. It should be released, along with all other information concerning British spying and agent provocateur activity in the Republic in the early 1970s.

David Burke is the author of The puppet masters: how MI6 masterminded Ireland’s deepest state crisis (Mercier Press, 2024).