Sean Murphy

It has been claimed that Molly Malone was a real person who lived in the late seventeenth century, and that records of her baptism in St Andrew’s Church and burial in St John’s Graveyard have been discovered. Accordingly, the Grafton Street statue of Molly is dressed in seventeenth- century style and is located around the corner from St Andrew’s Church. But is there any hard evidence that the baptism and burial records produced refer to Molly Malone, or indeed that she was even a real person? Could the Grafton Street statue be a major blunder based on invention and misconception?

Sometime in the last fifteen years or so, an anonymous individual decided without any supporting evidence that Molly Malone was a real person who lies buried in St John’s graveyard near Fishamble Street. This incipient legend was dignified by being committed to print in Viking Dublin exposed (1984, p. 103), where the alleged date of Molly’s burial is given as 1734. This work chronicles the unsuccessful campaign in the late seventies against the destruction of the Norse settlement site at Wood Quay, in order to make way for new Civic Offices. If it was thought that a little white lie would help to protect the remnants of St John’s graveyard (also on the controversial Civic Offices site), it was to be of no avail.

At sometime prior to the emergence of the unsupported St John’s graveyard burial yarn, a visiting American academic had apparently raised the possibility that Molly Malone might have died of typhoid fever contracted from consuming infected Dublin Bay cockles and mussels. Thus did the legend begin to grow, and it was to burst into full bloom during the Dublin ‘Millennium’ celebration of 1988, a festival which itself had dubious historical roots.

Frothy fantasy

The ‘Millennium’ thus encouraged an atmosphere where any frothy fantasy could supplant historical truth, and historians and others who objected were dismissed as cranks and party poopers. On 22 January 1988, at a press conference in St Andrew’s Church held to launch the ‘Dublin’s Fair City’ video show, it was solemnly announced that the baptism and burial records of Molly Malone had been discovered in the registers of St John’s Church (Irish Times, 23 January 1988). The entries in question relate to the baptism of a Mary Malone on 27 July 1663 and the burial of a person of the same name on 13 June 1699. St John’s Church was Church of Ireland in denomination and located behind Christ Church off Fishamble Street before being demolished in the last century. St John’s registers were published in 1906, and the originals are now held in the Representative Church Body Library.

While it is true that Molly is a form of the name Mary, no evidence was produced to show that the Mary or Marys listed in St John’s registers were known as Molly. Furthermore, there are quite a few Mary Malone entries in the Church of Ireland baptism registers of Dublin city, with many more again in the Roman Catholic registers, and there is no logical reason to choose the St John’s entries over the others. Finally, just as it was unwarranted to assume that Molly Malone was Church of Ireland and not Roman Catholic, so too was it capricious to assign her to the seventeenth instead of the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries.

Freelancing as a prostitute

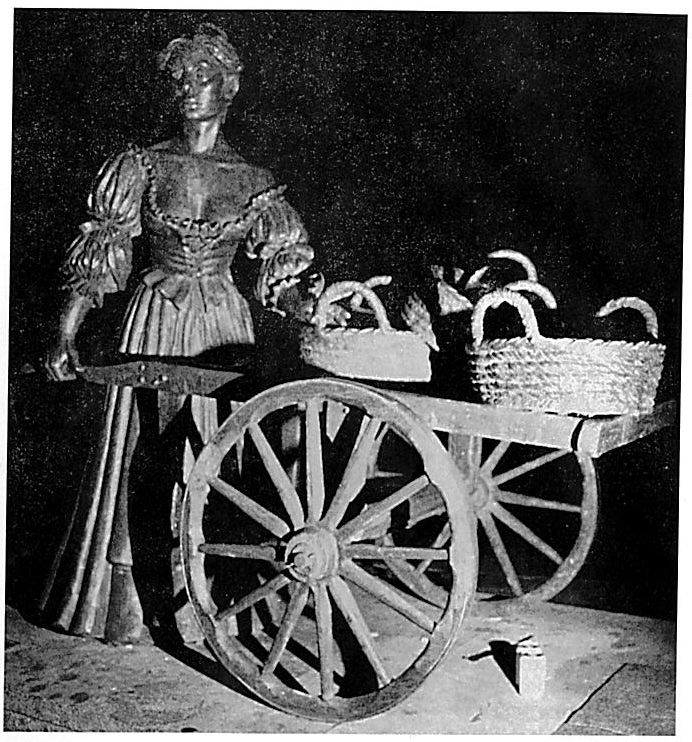

Such doubts did not trouble the partisans of the evolving Molly Malone legend, and the supremo of the Dublin ‘Millennium’ celebrations decided to commission a statue of the fishmonger. The contract to sculpt the statue was won by Jeanne Rynhart, who ‘researched the historical background for the statue’. The ‘research’ in question incorporated most of the elements of the Molly Malone legend as it then stood, but added a few new ones as well. Thus not only was Molly portrayed as a ‘Restoration citizen’ in seventeenthcentury dress, but with blithe disregard for the poor girl’s reputation, it was also claimed that she was ‘a prosperous trader who freelanced as a prostitute’. More than this, Molly’s ‘sales pitch’ was identified as eXtending from the Liberties to Grafton Street and St Stephen’s Green, and it was claimed that ‘she would have had clients in Trinity College, which was renowned for its debauchery at the time’. Molly’s statue was also clad with an extremely low-cut dress, on the grounds that as ‘women breastfed publicly in Molly’s time, breasts were popped out all over the place’ (Irish Times, 30 September 1989).

This was an avalanche of pure and unrestrained fantasy, but the worst blunder was yet to come. In 1989 the completed statue of Molly was placed at the junction of Grafton Street and Suffolk Street, on the stated grounds that this was around the corner from St Andrew’s Church where her baptism had taken place. It will be recalled that the original version of the legend had claimed that Molly was baptised in St John’s Church in 1663. The new claim seems to have been based on nothing more than a careless reading of the newspaper account of the January 1988 press conference (held in St Andrew’s) announcing the ‘discovery’ of the St John’s baptism entry!

The facts

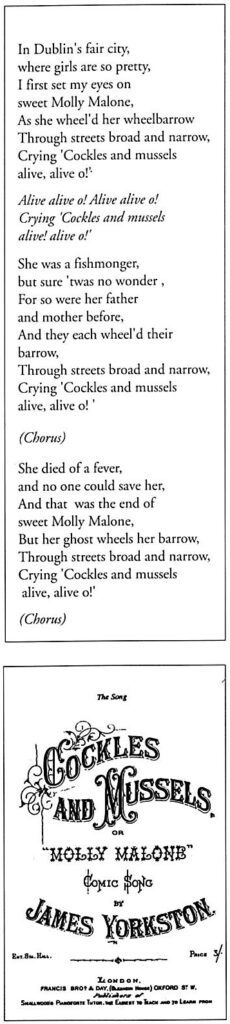

This then is the legend in all its glorious implausibility, but what of the facts, so far as they can be ascertained? In the first place, no version of ‘Cockles and Mussels’ predating 1850 has been found. Nor was it included in Colm 0 Lochlainn’s Irish street ballads or More Irish street ballads, indicating that it does not fit the mould of a conventional traditional song. The earliest version of ‘Cockles and Mussels’ traced to date was published in London in 1884 by Francis Brothers and Day, and a copy is held in the British Library. The 1884 version describes the piece as a ‘comic song’ written and composed by James Yorkston and arranged by Edmund Forman. The edition further acknowledges that the song was reprinted by permission of Messrs Kohler and Son of Edinburgh, so there must have been at least one earlier edition published in Scotland.

Enquiries to the National Library of Scotland failed to locate a copy of this earlier, and very possibly first edition, which was stated to be in number 35 of Kohler’s Musical Treasury, the date of publication of which was obviously sometime before 1884. ‘Cockles and Mussels’ was reprinted in editions of the Scottish Students’ Songbook in 1891 and after, where again it was credited to James Yorkston. According to Baptie’s Musical Scotland, 1894, Yorkston was a composer and editor of Messrs Kohler’s Musical Star, ‘for which publication he has arranged an immense number of part songs, Scottish and otherwise’. Further evidence of the Scottish provenance of ‘Cockles and Mussels’ and Yorkston’s authorship of it is provided by three twentieth-century editions of the song among the versions held in the Irish Traditional Music Archive. Two were published in Glasgow and all three credit Yorkston. Mention should also be made of another song entitled ‘Cockles and Mussels’, published in 1876 by James B Geoghegan. Although it contains the phrase ‘cockles and mussels, alive, alive, o!’, Geoghegan’s song is a distinct work with a different air and a different hero ‘Jim the Mussel Man’.

It would appear then that the version of ‘Cockles and Mussels’ sung today is not ‘traditional’, in the sense that it does not predate the 1880s or 1870s, and is the work of the Scottish-based composer James Yorkston. Yorkston may have been influenced by Geoghegan’s song of the same title, and both may have drawn inspiration from a traditional folk tune or tunes, as yet unidentified. Why Yorks ton set the song in Dublin, and not London or Edinburgh for example, is a point worthy of further investigation. It is not inconceivable that a real barrow girl in Dublin or even Edinburgh could have played a part in inspiring Yorkston, but it is more likely that the Molly Malone he portrayed was merely a type and not an actual person.

The song attributed to Yorkston was a ‘comic song’ replete with mock pathos, and having been performed in music halls, front parlours, student gatherings and elsewhere, it must have gained such popularity and been so widely dispersed that its origins were lost to memory and it was assumed to be just another anonymous folk song. As it was set in Dublin, it obviously attracted special interest there, and in time evolved into an unofficial municipal anthem.

Before the creation of the bizarre legend that Molly Malone was a real person who lived in the seventeenth century, many had an image of the fishmonger as a figure in a nineteenth-century Victorian setting. The evidence suggests that this impression is basically correct, and indeed this is the Molly Malone portrayed on the cover of Walton’s 1920s or 1930s edition of ‘Cockleds and Mussels’. She is set amid a Victorian Dublin scene, with a silhouette of Nelson’s Pillar in the background. Note also the details of Molly’s dress, and the fact that she wheels a barrow and not a handcraft as in Rynhart’s sculpture.

This nineteenth-century image of Molly Malone, backed up by research into period details and study of the origin of the song ‘Cockles and Mussels’, would have formed a better basis for a statue of the fishmonger. The Grafton Street sculpture is so false both in its form and in its setting that it might be better if it were removed to save the city further ridicule and replaced by a more authentic statue of Molly in nineteenth century dress sited, perhaps, in the Moore Street area, where Molly’s present-day successors, the fruit and fish-sellers, now play their trade. But sure what harm is it to take a few liberties with the truth, and isn’t it nice to have attractive fakes when so much of the real heritage of Dublin has been destroyed?

Sean Murphy is a genealogist and parttime lecturer in University College, Dublin.

Further reading:

S. Murphy, The mystery of Molly Malone (Dublin 1990).