On 2 July 1883, fifteen-year-old Bridget Carroll arrived at the Spark’s Lake reformatory in Monaghan to serve the remainder of a sentence that had been imposed on her four years earlier. She had been tried at Loughrea petty sessions in September 1879 on a charge that she ‘Did threaten to stab Anne Flynn’. She was found guilty and sentenced to a short term of imprisonment, followed by five years in a reformatory in Ballinasloe. This reformatory, which had been her home for nearly four years, was now closing, and she had made the long journey to Monaghan to serve out her sentence under the supervision of the St Louis sisters.

Genevieve Beale

The foundress of the Monaghan school was Genevieve Beale, a Catholic convert. She had been born Priscilla Beale to Protestant, possibly Quaker, parents in London in 1822. Her father was a property developer and speculator and it was the failure of his business that led Priscilla to take up a position with a family in Cork. While there, she became acquainted with Fr Mathew, the ‘apostle of temperance’, and Ellen Woodlock, who, though a Cork native, had been living at Juilly in France. When Priscilla converted, Mrs Woodlock encouraged her to enter the convent founded by the Abbé Bautain at Juilly. She was professed there in October 1848 and became Sr Genevieve. She trained as a teacher and became superior of the newly established St Louis convent in Paris. Priscilla Beale was not the only young woman to make the journey from Ireland to France. Ellen Woodlock’s recruitment drive had been a successful one and six Irish women entered the convent at Juilly at around the same time.In Ireland, meanwhile, the Catholic Church was seizing the opportunity presented by new legislation to expand. The 1858 act ‘to promote and regulate reformatory schools for juvenile offenders in Ireland’ gave state support to institutions run by voluntary organisations for ‘the better training of juvenile offenders’. Within a year six reformatories had opened, five of which were run by Catholic groups and for the exclusive incarceration of Catholic children. In late 1858 a small but influential group began to plan for such an institution in Monaghan. John Lentaigne, the inspector of prisons, Mrs Lloyd, the mother of Lady Rossmore and also a convert, Ellen Woodlock, whose family owned the woollen mills at Blarney, and the bishop of Clogher decided to open a reformatory in Monaghan. Ellen Woodlock wrote that ‘the bishop, Mrs Lloyd and Mr Lentaigne request a well-bred, well educated French sister’ for the task. The bishop wrote to the abbé in France to ask that a foundation of the St Louis order be established in Monaghan. Three sisters, Genevieve, Clare and Clement, arrived there on 6 January 1859 after an eventful journey from France, with very little money and an expectation that a house awaited them. There was no house and, after some nights spent in a hotel, they moved into a small, unfurnished house.

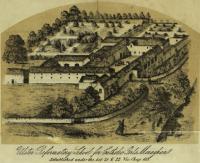

Spark’s Lake brewery

They survived for some time by teaching local children, until they were rescued by Charles Bianconi, who purchased an old brewery at Spark’s Lake. The sisters moved into the brewery and received their first reformatory child on 14 October 1859. Ellen Brown was an eleven-year-old girl from Belfast who had seven convictions prior to her reformatory sentence. Genevieve Beale wrote of her that she ‘presented a pale and emaciated appearance, from the habitual use of strong liquors, during the short periods when in the enjoyment of liberty, and owing to the rigours of a refractory cell, while undergoing punishment in gaol’.

By 1862 the inspector of reformatories was writing that the Monaghan school was receiving ‘some of the most vicious and refractory girls’ he had ever seen. These included girls who were rejected by other reformatories, such as prostitutes or those suffering from venereal diseases, and girls whose behaviour meant that other schools, particularly High Park in Dublin, could not cope with them. By 1865 the school had 39 inmates. The inspector said of Genevieve Beale that:

‘Were it not for the manager’s [Sr Beale’s] indomitable perseverance in her mission, and her courage in accepting the transfer from High Park of the worst class of Dublin girls, eight at least would have been thrown upon the world and into utter depravity. There are none so wicked, so violent—so, to all human judgement, lost—as to be beyond the scope of her zeal and sympathy.’

When the representatives of a government commission visited Spark’s Lake in January 1883 they were told that, in its early years, such was the violence of some of the girls to each other and to themselves that strait waistcoats were provided and sometimes used.

Ballinasloe reformatory

When the Monaghan school opened, it described itself as being the only reformatory for Catholic girls in the north and west of Ireland. This situation would not change until 1864, when Connacht’s only reformatory opened. On 7 December 1863 Mary Burke, the superior of the Mercy convent in Ballinasloe, wrote to the chief secretary, Robert Peel, that she had been preparing a building in the town for the reception of female juvenile offenders. She was acting under the direction of her bishop, Dr Derry. The inspector, whose job it was to recommend the building and the manager to the chief secretary, found a well-fitted-out building and a manager who was ‘fully prepared to receive twelve children, and has the complete school uniform, with beds, bedding and bed clothing’ when he visited. The new school received its first girl, Margaret Seery, in March 1864. Margaret was ten years old. She had been born in the workhouse and was described by the inspector as an ‘inveterate thief’ who had been trained to steal by her mother. She was arrested in Sligo with a woman, probably her mother, and found guilty of stealing a purse containing five shillings. She was given a sentence of one calendar month in Sligo gaol and five years in the new reformatory. Margaret found herself with few companions in her new home. Despite her preparations, Mary Burke’s school was undersubscribed, so that by 1866 there were only nine inmates.

‘Disposal of the inmates’

The great test of the reformatory system was that the children who were sent to the schools would leave them as honest and industrious individuals who were sufficiently trained to become self-supporting. ‘Disposal of the inmates’ was a challenge for all of the reformatory managers, and the inspector’s office in Dublin Castle requested that they keep a record of those who were released for three years after they had left the institutions. Both Mary Burke and Genevieve Beale tried to find work for the girls when they left. In 1862 Genevieve Beale wrote that ‘the future of our poor children is a source of increasing anxiety to us’. Mary Burke could tell the inspector in 1873 that, of the five girls discharged in the previous year, one remained in the school until a position was found for her in Ballinasloe, one had gone to her brother in New York, one was ‘keeping house for her father’, and two were ‘giving perfect satisfaction’ as general servants. Where it was felt that the girls would relapse into crime, or if their parents were criminal, great efforts were made to remove them from their former associates. In 1865 the inspector of reformatories reported what had happened in Monaghan when two girls—cousins—were about to be released from the school:

‘Their relatives, a gang of wandering tinkers, had been prowling about the reformatory, and were driven off by the constabulary. They went away, declaring their intention of returning on the day of the girls’ discharge . . . A steamer was to sail from Londonderry three days before the expected day of discharge. [The manager] telegraphed me to obtain a pardon from the chief secretary at once . . . and three days before the day of discharge the two girls were sailing for New York.’

The mother and grandmother of one of the girls were in convict prisons, and the father and brother of the other girl were in a prison and a reformatory. Genevieve Beale did not always succeed in removing the girls; two others were taken by their mothers at the expiration of their sentences in Monaghan ‘to live upon the wages of their sin, although the money for their passage and outfit, and honest employment in Canada, were secured for them’.

For some of the discharged girls, their passage to North America would prove eventful. ‘A.M.’ emigrated to New York and was married ‘immediately after landing’ to one of the ship’s crew. ‘M.B.’ received a proposal of marriage from the mate of the vessel in which she sailed to Boston, which she declined. ‘C.T.’ arrived at Monaghan a ‘depraved and immoral girl’ who had absconded from High Park, and was the recipient of a similar proposal from a fellow passenger, a commercial traveller, en route to New York. She refused him, on finding that he was ‘not religious’.

By the time that Bridget Carroll arrived in Monaghan, many changes had occurred in both the school that she was leaving and the one to which she was sent. Ballinasloe had never reached its capacity of inmates, although its numbers were boosted for a time by the transfer of refractory children from industrial schools. In 1883 Mary Burke applied for recertification of the reformatory as an industrial school. Her application was granted and she remained the manager until 1894. When the representatives of the Reformatories and Industrial Schools Commission visited Spark’s Lake four months before Bridget’s arrival, they noted a ‘general improvement in character of the committed children’. Genevieve Beale had died at the age of 56 in 1878. The school that she had founded closed in 1903. Bridget Carroll remained in Monaghan until October 1884. She emigrated to New York and in the two years after her discharge was reported to be ‘doing well’. HI

Geraldine Curtin recently completed a Ph.D at NUI Galway on juvenile crime and poverty in Connacht in the nineteenth century.

Further reading

A sister of St Louis, Memoir of the life of Sister Mary Genevieve Beale (Dublin, 1904).