By Barry Sheppard

The year 1949 marked a watershed in post-war America. According to theologian Richard Gribble, in the years immediately following the Second World War Americans lived through an unprecedented period of prosperity and fear. A united push behind the war effort had been able, at least temporarily, to smooth over some of the racial cracks in society. Economic prosperity that had gathered steam during the conflict flourished when the guns fell silent. The ghosts of the Depression era were finally exorcised. Yet, as the United States assumed the role of hegemon of the West, its former ally in the fight against the Nazis, the USSR, was now viewed as a threat to that dominance.

While the Soviet Union emerged from the Second World War in a comparatively weakened state, it still loomed large in the imaginations of American leaders and their influential allies. Winston Churchill’s 1946 ‘Sinews of Peace’ (Iron Curtain) speech, given in Fulton, Missouri, set the era’s political tone. It was delivered at a time when the Truman administration was ‘drifting towards Churchillian notions of confrontation’ with the Soviets, but 1949 was the year in which the temperature reached boiling point. In August the Soviets conducted their first successful nuclear weapons test. A matter of weeks later, Mao’s Red Army defeated the Chinese nationalist government, a result viewed as ‘a victory for the Kremlin’.

The perceived external threats posed by an increasingly confident Soviet Union and China were compounded by fears of communist infiltration on the domestic front. A nine-month trial of eleven American communists charged with conspiring to overthrow the United States government captured the public’s attention, amplifying already palpable paranoia. It was into this political tinderbox that the rural Irish Catholic leader Fr John Hayes entered that autumn.

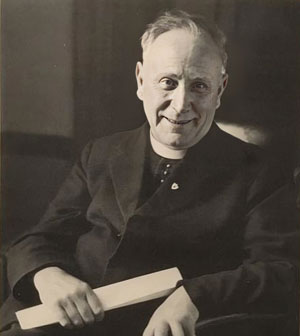

FR JOHN HAYES AND MUINTIR NA TÍRE

Hayes, the founder and figurehead of the rural community development organisation Muintir na Tíre (the ‘People of the Land’), was on a mission to secure American funds for his rural revival projects in Ireland. The organisation, which was founded as a rural co-operative in Tipperary in 1931, was now a papal-inspired vocationalist organisation with branches across the state. It also had bills to pay. Reluctant to seek state funding at home, Hayes looked to the Irish diaspora for survival.

While scheduled to attend an international Rural Life Convention in Columbus, Ohio, Hayes was determined to take the Muintir roadshow to Irish-American communities in New York and Boston. Encouraged by some influential Irish-Americans at home, notably Joseph E. Carrigan, head of the Economic Co-operation Administration in Ireland, Hayes was advised not only to go to the United States but also to play up Muintir’s anti-communist credentials for American audiences. Hayes’s contact in the United States, Irish-American conservative Martin Quigley Jr, informed the rural leader in a telegram before his departure that anti-communism was ‘hot stuff here at the moment’.

MARTIN QUIGLEY JR

Quigley, a prominent Catholic activist with ties to the media and the Hollywood movie industry, understood the power of publicity and intrigue. He recognised that an Irish priest who had a plan, no matter how vague, to rid his country of communism was a headline-grabber in the middle of a red scare. Most interesting, though, was Quigley’s career as a secret agent. During the Second World War he worked undercover for the Office of Strategic Services (the forerunner of the CIA). His mission was to investigate the sincerity of Ireland’s wartime neutrality.

Using the cover story that he was a scout for the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America, Quigley landed in ‘Emergency’ Ireland to gather information. In his own words, his cover story was ‘a passport to be able to communicate with all kinds of people at every conceivable level’. It is believed that he first met Muintir na Tíre members during this mission. The organisation had recently established a mobile cinema enterprise, which showed films of high moral calibre in community halls across rural Ireland. Such an enterprise would have appealed to the American agent.

With Quigley as his PR man, Hayes became the darling of the American print media, who christened him ‘Ireland’s Rural Apostle’. By the time of his arrival in New York, Muintir was being hailed as Ireland’s social and economic answer to atheistic communism. Hayes’s selling point as a leader of a religious movement that stood firm against communism quickly opened doors, including those of the influential American Catholic hierarchy.

ARCHBISHOP RICHARD CUSHING

Another figure who championed the Muintir cause was the archbishop of Boston and de facto private chaplain to the Kennedys, Richard Cushing. A Bostonian of Irish parents, Cushing was described as the ‘magna vox of the hierarchy in the United States’. Although he had briefly met Hayes in Ireland earlier in 1949 while on a pilgrimage, they became steadfast allies after Hayes’s arrival in the States.

Cushing has been described as ‘an anti-communist polemicist’ who ‘stridently and consistently’ attacked domestic and international communism. It was not this, however, that drew the men to one another but rather Irish political and constitutional matters. Cushing was noted as a man of ‘practical goodwill towards Ireland’ and its people. He shared Hayes’s Irish republican views and often preached from the pulpit on Irish matters, including the Easter Rising and partition. In fact, in 1948 he met with Frank Aiken and Éamon de Valera on their anti-partition tour in the United States.

Irish political matters were raised during Cushing’s first meeting with Hayes on American soil. Hayes, a hopeless romantic, left the meeting much enthused. He rhapsodised about Cushing’s concern for the ‘old country’, noting that his views were ‘the words of a man who loved Ireland deeply and sincerely’. Kind words, however, did not pay the bills. Hayes needed to boost Muintir coffers and Cushing was instrumental in making this a reality. He organised a large fund-raiser in Boston on 25 November 1949. Around 1,000 of the most affluent and influential Bostonians gathered to hear about Hayes’s anti-communist crusade in the old sod and to contribute financially to its success.

Taking to the stage, Cushing played the role of the ‘hype man’ for the headline act. Exclaiming that the Irish nation’s success depended on Muintir na Tíre, he easily won over the audience. This left Hayes with little to do except rehash a pitch that he had already perfected. Huge sums were raised that night. Cushing even passed through the crowd with an upturned hat and umbrella, prodding guests for extra donations. Despite Hayes’s moral reservations about that technique, he was grateful for Cushing’s efforts.

The large sums of money that entered Muintir’s coffers demonstrated the importance of the Irish diaspora in the organisation’s story. The Éire Society of Boston, an organisation formed to spread ‘awareness of the cultural achievements of the Irish people’, contributed $1,000. Similar-sized donations came from the Boston Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Tipperarymen’s Association. Cushing, however, was the man of the hour. He pledged $1,000 per month for the next five months for Muintir’s domestic projects, which by this stage included an active role in Irish rural electrification.

American money put the organisation on a secure financial footing, at least in the short term. Muintir’s monthly newsletter, The Landmark, provided updates throughout 1950 on how it transformed the organisation’s fortunes. Cushing’s role in preventing financial doom was not quickly forgotten. He was a guest of honour at Muintir’s Tipperary headquarters in 1953 while on another Irish pilgrimage.

HIGH-NOTE CONCLUSION

Hayes’s American campaign ended on a high note in mid-December in New York, where a lavish send-off was organised by the United Irish Counties Association (UICA) at the Hotel Henry Hudson. The UICA was another influential Irish-American body that opened its doors to the Muintir cause. With membership in the tens of thousands throughout the New York Metropolitan Area, it was a valuable ally to have. Again, the élite of American civic society came out in force to honour Hayes and ‘furnish financial aid’ to the rural leader.

Guests who attended Hayes’s farewell included John Cashin, president of the Tipperarymen’s Association, and John J. Sheehan, chairman of the New York St Patrick’s Day Parade Committee. The hierarchy was represented by Monsignor Patrick O’Donnell of St Jerome’s Church in the Bronx and Cardinal Francis Spellman, archbishop of New York. Spellman even offered his services in sponsoring an associate guild of Muintir na Tíre in the Big Apple.

Another notable high-profile guest and advocate was New York Assistant District Attorney Alexander Rorke. The shark-like Assistant DA gained a fierce reputation over the years for prosecuting suspected communists and was therefore welcomed with open arms. One of the more high-profile figures who fall foul of Rorke during that period was Irish Labour leader Jim Larkin.

LEGACY DID NOT ENDURE

The Hudson event garnered considerable media attention, which again painted Muintir as a bulwark against communism. The New York Advocate highlighted Ireland’s entwined history with America. It positioned the United States as ‘the hope and glory of the world’, with Ireland a junior partner in a global civilising mission. Hayes would have welcomed such a perspective. Muintir’s American campaign of 1949 was a massive success. Irish-American organisations and influential members of the American hierarchy combined to provide financial aid to Hayes, securing his organisation’s future at home. The rural leader, for his part, revelled in his new-found stature. He was the right man in the right place at the right time, and many Irish-Americans fell for his charm.

It was a romance, however, that did not last. With Hayes’s death in 1957, Muintir na Tíre lost a capable leader and a charismatic figurehead. While others stepped up, none had the magnetism with which he was gifted. One of his most able lieutenants, the writer and broadcaster Stephen Rynne, travelled to the United States just over a decade later to promote his 1960 biography of the deceased cleric. Although he called on many of the same figures in Irish America, he was met with a very different response. Where Hayes found enthusiasm and open pockets, Rynne found apathy and indifference. Even Muintir’s steadfast ally Cardinal Cushing could not muster previous levels of enthusiasm. Although he maintained devotion to Hayes’s aims and memory, he told a deflated Rynne that ‘no one here is interested in Canon Hayes’. The public, Rynne discovered to his dismay, were more interested in Brendan Behan’s latest exploits than in John Hayes. America, it seemed, had moved on.

Barry Sheppard was the presenter of History Now on Belfast’s Northern Visions Television and is an Associate Fellow of the Institute of Irish Studies, Queen’s University, Belfast.

Further reading

M. Tierney, The story of Muintir na Tíre 1931–2001—the first seventy years (Tipperary, 2004).