By Charles Tyner

At the time of the Civil War, the United States was a growing power but not yet a ‘great’ one. Vulnerable to the existing European powers, it had to navigate its way carefully through any diplomatic crisis that might undermine it, of which there were several. One such episode was the Trent Affair. How was that viewed by The Nation newspaper, voice of the Young Irelanders?

Crucial to the success of either belligerent, Union or Confederate, was persuading European powers, particularly the United Kingdom and France, to enter the war on their side or, at worst, ensuring their neutrality. There were major economic factors for the Europeans to consider; both British and French mills depended on steady supplies of southern cotton. Moreover, Britain was aware that undertaking a war with the United States, either alone or as an ally of the Confederates, would cut off vital shipments of American food, endanger the British merchant fleet and very likely lead to an invasion of Canada. European interests were, they believed, best served by peace in America, but they also believed that restoration of the Union was impossible. When hostilities began, they opted for neutrality. To ensure that this decision was not revoked, it was vital for the United States not to antagonise the European powers.

ATTITUDE OF THE YOUNG IRELANDERS

From the beginning of the war, Young Ireland supported the Confederacy. Even before the outbreak of hostilities in April 1861, on 5 January The Nation vehemently castigated the North, which had

‘… violated its compact, violated its obligations towards the Union, and its fealty to the Constitution, by a course of conduct which at any moment for years past would technically have justified the South in withdrawing from the Confederation’.

Rejecting any suggestion that the paper might be sympathetic to slavery, the writer argued that it was really for the North to secede, since it was the North which was abrogating the Constitution. It could then honourably fight to ‘destroy an institution … deemed by the South essential to its very existence’.

For the revolutionaries of Young Ireland, ideology had begun to take on a ‘racial’ tinge. As Bryan McGovern has noted, there was a tension between a growing consciousness of nationhood, shared across Europe and marked by revolutions in 1848, and an invented ‘race’, which at that stage was seen as coterminous with nationality. Nationalism, as defined by Young Ireland, could be inclusive, and in Ireland it needed to be in order to accommodate Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter. Concepts of race, though, are by definition exclusionary. This tension made it possible for the Confederate cause to be supported despite the practice of chattel slavery. When Meagher and Mitchell ‘broke’ with each other, it was over the (American) Union, not slavery. Mitchell not only supported the Confederacy but also was outspoken in his defence of enslavement and agitated for the reintroduction of the African slave-trade.

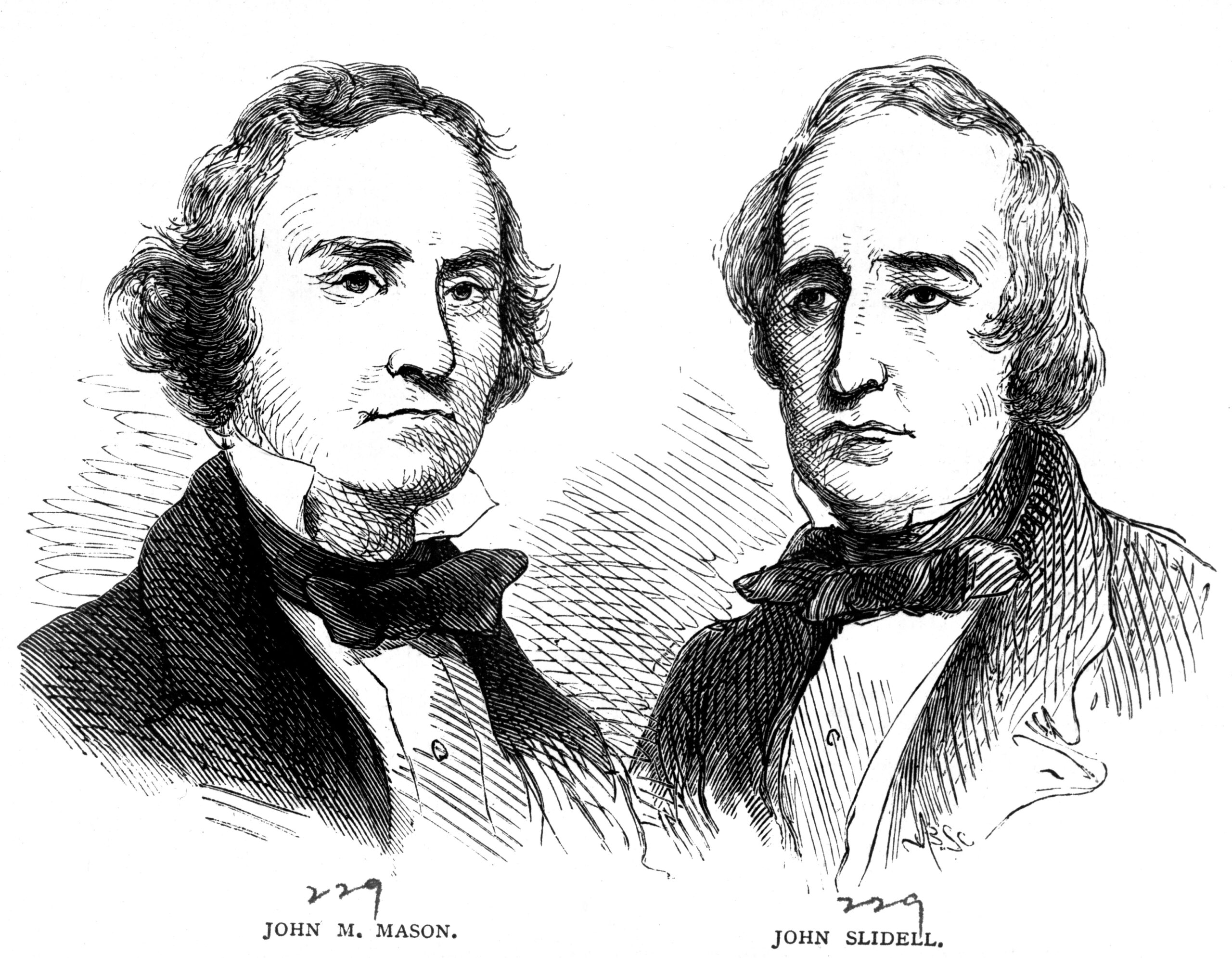

In August 1861, Confederate President Jefferson Davis decided that he needed to increase southern diplomatic efforts in Europe. He appointed John Slidell of Louisiana and James Mason of Virginia as envoys, with the objective of sailing to Britain to present the Confederate case for recognition.

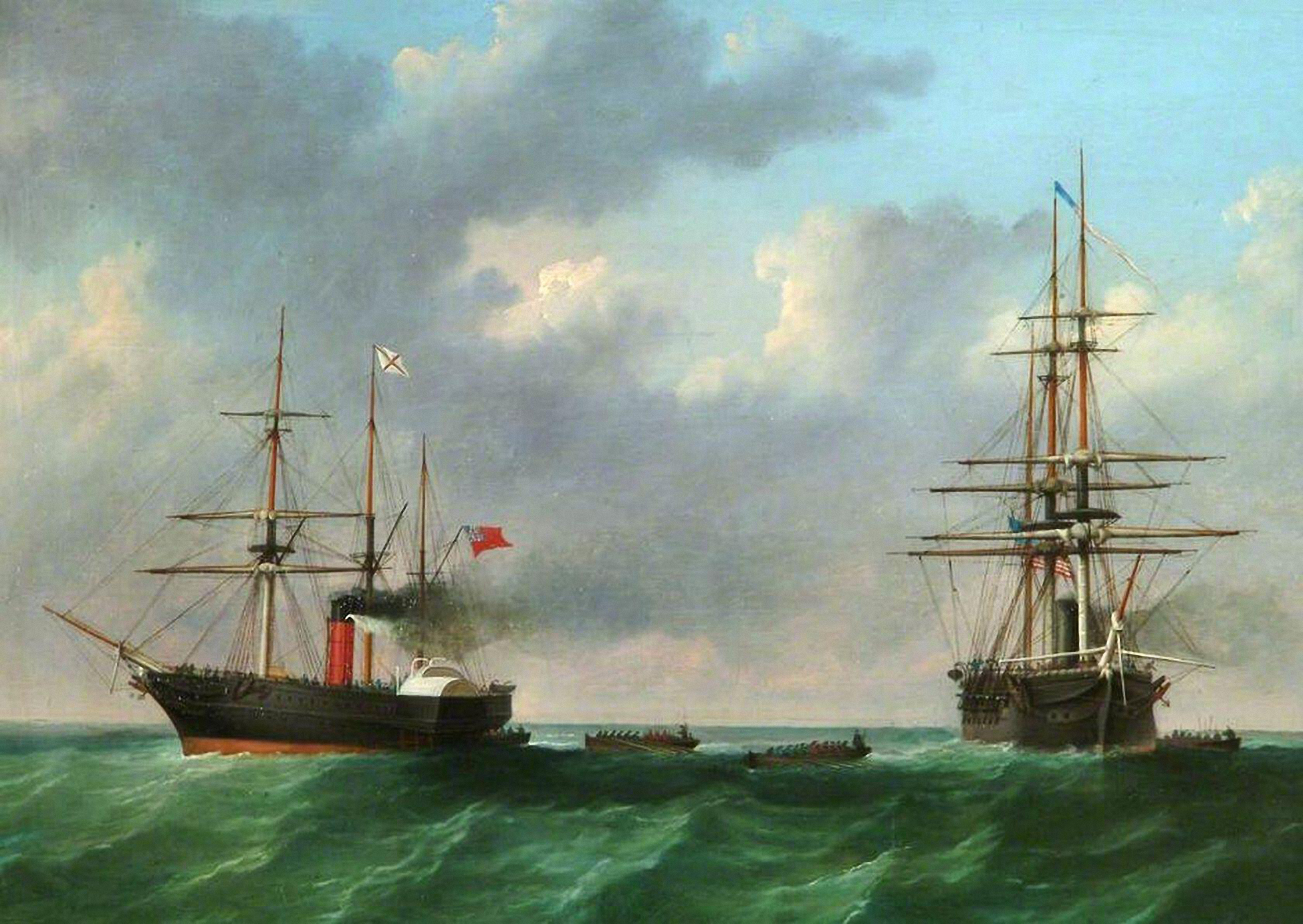

Evading the blockade of southern ports, the envoys reached Spanish Cuba and boarded the Royal Mail steamship Trent. The plan was not kept secret and one Captain Charles Wilkes, commanding the USS San Jacinto, learned from a newspaper that Mason and Slidell were scheduled to leave Havana on 7 November, bound for Britain. Knowing the course the Trent must take, Wilkes waited to intercept and, with two shots across the bow, brought the Trent to a halt on 8 November. Declaring the envoys to be ‘contraband’, Wilkes took them into custody and allowed the Trent to continue its voyage.

When news reached the North there was initial rejoicing but, even before Britain reacted, some doubts about the legality of the action were expressed. Some compared it to the Royal Navy impressment of American mariners on the high seas, which was strongly resented by the United States and had been a contributing factor in the outbreak of war in 1812.

News of the event reached Britain on 27 November 1861. The British government was outraged and threatened war if the envoys were not released and an apology to Britain proffered by the Washington government. To back up the demand, 3,000 troops were dispatched to Canada.

COVERAGE AND REACTION IN THE NATION

The time taken by the Trent to sail from the Bahamas explains the time-lag between event and coverage in The Nation. On the first occasion on which it commented on the affair (30 November 1861), The Nation summarised the week’s events, gleefully commenting on the taking of the Confederate envoys: ‘The act was worthy of the spirit, daring, and dash of the Americans; it was one to make Irish hearts jump with joy’. The writer teased out what he saw as the options for England:

‘If the English do not resent this violation and defiance of their flag, then indeed is their honour gone for ever, and the world will be able to regard them as a spiritless people, whom any strong nation may insult with impunity … But if they do resent it—then will have come a great time for Ireland.’

The writer pointed out, in highly charged language, what he was certain would happen:

‘Then will the Irish race in America rush to arms, and bound into the battle! Yes, then will the forces of England find in their front such desperate men as crushed their ranks at Fontenoy to the cry of “Remember Limerick” … they can, most certainly, establish the independence of Ireland.’

The editorial comment was every bit as gleeful, presented under the headline ‘WAR OR DISHONOUR’. It began with admiration of the American action, and continued in the vein that English strength and daring were found wanting. The writer boldly asserted that ‘The Americans will not retract’. From this point, however, the writer moved from the fantastical to the fanatical, articulating a bloodthirstiness that would have found no approval from constitutional nationalism, and perhaps little enough from readers of The Nation:

‘No prophet’s voice is needed to foretell what all foresee … War between England and America!—between England and the Irish abroad; between England and millions of our nearest and dearest kindred—our very own flesh and blood. There are one hundred thousand armed and disciplined Irish soldiers in America … In that hour the bitter memories of a lifetime—memories the most terrible that ever exiles bore—would find vent in the cry for vengeance …’

In the next edition of the paper (7 December 1861), the issue was dealt with almost flippantly in places. The ‘This Week’ section was certain that the Americans would never surrender the agents and that this must, inevitably, lead to a declaration of war, for which, it felt, the British had no stomach. It noted that various imperial considerations ‘tend to cool the warlike ardour of the Britons, and to cause that oozing out of their valour at their fingers’ ends which is already apparent’. The most grudging and insincere apology from the Americans would satisfy the British, but for the editor it was all too late. The Americans were ‘in very fair humour at present. Some of them are chaffing John Bull very pleasantly.’ Turning to the Irish element of the population, the writer noted that, ‘when the British demands are made publicly known, then will the fury of the populace burst forth, and the quibbles of international law be forgotten, and the whole country rise as one man to arms!’

In the same day’s issue, the editorial talked indirectly about the implications for Ireland:

‘But there are nations in Europe for whom the result, which is called most dreadful, has no terrors—nations that are suffering, and have long suffered beneath a heavy load of oppression, and who look to those lurid streaks that are now ominously stretching across the dawn with feelings of hopeful emotion’.

The contortions here are worth analysing. Literally a few weeks earlier, The Nation was displaying its sympathy for the Confederacy against the Federalists; now it was lining up behind those same Federalists in their quarrel with England. It cannot be entertained that they would hope for anything other than an American victory, given the ‘heavy load of oppression’ imposed on Ireland by the British. The support for the Confederacy could therefore be interpreted as mere opportunism, playing to perceived parallels between the southern states and Ireland as victims of an unsympathetic industrialised behemoth. Moreover, the paper’s support for the Federal government was equally opportunistic, as it was solely predicated on the Americans dealing a blow to the British, irrespective of who had right on their side. It was a vindication of twin principles: ‘My enemy’s enemy is my friend’ and ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’.

By the following edition (14 December 1861), excitement was approaching fever pitch. The writer relished the prospect of war between England and the United States:

‘England cannot now retreat with honour from the position she has taken up. She is committed to it before Europe … America, in this matter, cannot yield to the demands of England without incurring irreparable dishonour!’

Both protagonists were trapped by the demands of honour. War was inevitable:

‘… a few days more and the tale will be told—the great words will be spoken—words to make some men tremble, and to make others raise their hands gratefully, and own that God is just—to make them say that guilt is punished at last, that rapine and murder do not thrive for ever, that the good things of this world are not given over for all time to any strong hand that may wrest them from weaker possessors, that honour, honesty, fidelity, are not visited on this earth with a perpetual malediction’.

Guilt, murder and rapine were being assigned to Britain, the strong hand wresting ‘good things’ from Ireland, which was acknowledged to be weaker physically but decidedly not morally. Ireland possessed honour, honesty and fidelity, and the curse that had accompanied these attributes was about to be lifted.

The writer then took a phrase from the Catholic Mass and slipped into a quasi-religious fervour:

‘Sursum corda! Lift up your hearts, ye people who have long been bowed beneath oppression—whose hearts have been steeped in bitterness—whose souls have been darkened with despair! Lift up your hearts! a time of wonders has come upon you. It is a dream no longer. Hush your sad music—utter complaints no more—stand erect—accustom your eyes to look upon the blessed light. It is a dream no longer.’

Returning to this vale of tears, the author summarised the situation thus:

‘After centuries of suffering and oppression, after weary ages of bondage, the nationality of our country … has again established its active existence, and made a demand for its recognition’.

Coming dangerously close to incitement to violence, or at least giving comfort to an enemy, the writer issued a rallying call: ‘We call upon our countrymen to give to this reclamation [of nationhood] something greater than an utterance, and more enduring than a sound’.

‘ONE WAR AT A TIME IS ENOUGH’

It was not to be. War was in neither country’s interests, though possibly tempting for both, given their mutual resentment. Ireland’s cause was only of interest to the Federal government as a recruiting sergeant for the Union army; to the British government, the country was a continuing irritant, too strategically positioned to permit independence but too rebellious to warrant investment in anything other than security measures.

Realising the danger inherent in going to war with the British Empire when already fighting the Confederacy, Secretary of State William Seward persuaded Lincoln that it would be better to release the envoys. Lincoln agreed, adding laconically that ‘one war at a time is enough’, and the matter was thus resolved peacefully. On 25 December Seward informed the British that Captain Wilkes had indeed acted on his own initiative and, while not violating international law, had made certain technical errors. The two diplomats would be ‘cheerfully liberated’ and turned over to the British diplomatic representative, Lord Lyons.

On 8 January 1862, a ship docked in Queenstown (Cobh) announcing a resolution of the affair. On 11 January The Nation suggested that they had been misled by the British press, but also emphasised, not without some satisfaction, that Britain, too, had suffered:

‘There is the end of the American difficulty. We learn now that it never was the serious matter represented by the British journals … [T]he mistake has cost England much trouble, considerable anxiety, and more than two millions of money—it has cost America, nothing. There was no occasion for the despatch of all those steamers, or the hurrying off of all those crowds of troops, and the forwarding of those enormous loads of war munitions to Canada.’

Thereafter, The Nation returned to supporting the Confederacy.

Charles Tyner is a recent graduate of Maynooth University’s MA in Irish History programme.

Further reading

A. Andrews, Newspapers and newsmakers: the Dublin nationalist press in the mid-nineteenth century (Liverpool, 2021).

D.K. Goodwin, Team of rivals: the political genius of Abraham Lincoln (New York, 2005).

J. Hernon, Celts, Catholics and Copperheads (Ohio, 1968).

B. McGovern, ‘Richard O’Gorman and Young Ireland on race, class, and culture in nineteenth-century Irish America’, New Hibernia Review 26 (2) (2022), 112–31.