By Aindrias Ó Cathasaigh

The word ‘iconic’ is used far too often, but there are times when it applies. Ever since James Connolly had the slogan ‘We Serve Neither King Nor Kaiser But Ireland!’ hung on Dublin’s Liberty Hall in 1914, it has had considerable influence. The photograph of Citizen Army members mobilised in front of it has been repeatedly reproduced and is instantly recognisable. As well as featuring in discussion of Connolly’s work, the slogan has been regularly invoked in anti-war discourse since.

LONG PEDIGREE

The phrase itself had a long pedigree before Connolly employed it. In one of the so-called N-Town Plays, a series of anonymous English mystery dramas from the fifteenth century, Herod is made to say that ‘Nother kyng nor kayser’ are as powerful as he. The kaisers of the Holy Roman Empire hadn’t yet appeared in the time of Herod but they ruled when the drama was written, and the phrase must have had some currency. Its positive counterpart is found in the thirteenth-century English romance Havelok the Dane, which speaks of a meal fit for ‘King or cayser’. Often it was just an alliterative couplet with no political connotations at all.

The idea of serving neither ruler originates with American historian John Lothrop Motley. His Rise of the Dutch Republic (1856) describes one of the accusations against Philip de Montmorency at his treason trial in 1568, ‘that he was thenceforth resolved to serve neither King nor Kaiser’. Motley’s history was very widely read and one of his readers was James Connolly, who quoted the book in his 1909 pamphlet Socialism made easy, praising Motley as a ‘painstaking historian’. So it seems that the notion of serving neither king nor kaiser came to him from this source.

FIRST APPEARED IN THE IRISH WORKER

It became a political slogan for Connolly with the outbreak of war in 1914. He was the prime mover in organising a meeting of separatists, and in making ‘A declaration of Irish neutrality’ the pivot of their opposition to the war. An Irish Neutrality League was established, with Connolly as president and main speaker at its inaugural public meeting on 12 October.

Shortly after, James Larkin sailed for the United States, and Connolly took over his positions as leader of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) and the Irish Citizen Army, and editor of the Irish Worker. The first issue of that paper under Connolly’s editorship on 24 October retained its distinctive masthead, but underneath it ‘We serve neither King nor Kaiser’ appeared in bold capitals bigger than any of the headlines and was there every week thereafter. The slogan was clear, not just to the thousands who read the Irish Worker but also to anyone else who saw them doing so, or even saw the paper on sale.

Soon after, a linen banner attached to a board was affixed to the front of Liberty Hall, head office of the ITGWU: ‘We serve neither King nor Kaiser BUT IRELAND!’. As well as the often-neglected exclamation mark, the slogan from the Irish Worker had been extended to express not just what ‘we’ were against but also what ‘we’ were for—namely ‘Ireland’.

Connolly had often deprecated similar invocations of the nation. Talk of ‘Ireland’ in the abstract usually obscured the harsh reality of the classes that made up Irish society, he argued, and the competing interests that flowed from that—a way of fooling the working class that ‘we were all in it together’. In his Story of the Irish Citizen Army (1919) Seán O’Casey was to claim that Connolly’s banner was ‘directly contrary to his life-long teaching of Socialism’.

IRISH NEUTRALITY LEAGUE

For all that O’Casey was grinding an axe of his own, he would have had a point if this had been a personal initiative of Connolly or even of his union. It makes more sense to see it in the context of the Irish Neutrality League, however. At its launch Connolly had emphasised how broad the League was:

‘There were labour men there, and men who by no stretch of the imagination could be called labour men … They represented many diverse ideas that for the time being were relinquished, so that they could come together on a common platform. But having mentioned the things they disagreed on, he would now turn to the one thing upon which they all agreed, namely that the interests of Ireland were more dear to them than the interests of the British Empire (loud applause).’

Asserting the interests of Ireland and delineating them from those of the British Empire at war was the solitary plank of this campaign, and the one put up on the front of Liberty Hall. There is no evidence that this was a collective initiative of the League, though, and it reflects a greater boldness and impatience on the part of Connolly than the other groups involved with it. It is significant that the premises of other separatist organisations in Dublin were not similarly adorned. As it turned out, the League fizzled out after a few months.

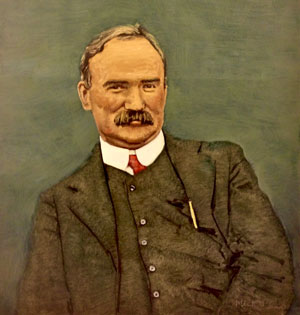

THE PHOTOGRAPH

What ensured the slogan a place in the annals is that Keogh Brothers, one of the city’s leading photographic studios, were engaged to immortalise the banner. A group of the Citizen Army were mobilised to stand at arms outside Liberty Hall as at least three photos were taken. The result is well known to the most superficial enquirer into the history of the period.

One thing noticeable in the picture is that 35 Citizen Army men at most can be seen, if everyone with a shoulder strap or the army’s distinctive slouch hat is counted as a member. Just over half of them are armed with rifles or replicas. The numbers are swelled by some 50 people in civilian attire standing behind them, with Connolly prominent among them. About 70 onlookers stand on either side. Two women are visible at the upper windows of Liberty Hall, almost as if standing guard on the banner. Puddles on Beresford Place show that they didn’t have a nice day for it.

A photograph of the Citizen Army appeared in the Gaelic American of 21 November, although it was taken some time earlier, as evidenced by the presence of Larkin (usually cropped out of later reproductions). In comparison to the Liberty Hall photo, there appear to be slightly more of them, better armed and in stricter formation. This would suggest that the mobilisation for the Liberty Hall picture was somewhat hurried, making do with the men and equipment available at short notice.

A postcard was made from the photo, with some of the onlookers cropped out, especially on the right-hand side. These postcards were advertised for sale at 2s. 6d. each in the Irish Worker. Not only would this raise much-needed funds to equip the Citizen Army but it would also ensure that the defiant slogan would be broadcast even more widely. (One of these postcards fetched €200 at auction in 2014.)

NEUTRALITY?

Despite the conventional reading of that slogan and the name of the League it appeared in connection with, Connolly’s policy in 1914 cannot accurately be described as one of military neutrality. He wrote on the outbreak of war that ‘we should be perfectly justified’ in joining a German invasion force if doing so could end British rule in Ireland. This perspective—a highly notional one, in view of the weak forces to hand—envisaged Irish forces fighting alongside the German army in the interests of Irish independence, not subordinating themselves to the Kaiser but seizing the opportunity of their common hostility to the British Empire. Connolly was advocating an independent policy for Ireland in the fortunes of war but not staying outside the conflict.

He came close to making excuses for the Kaiser, if not serving him, in some of his early analysis of the war. Britain was fighting ‘the war of a pirate upon the German nation’, he wrote, attempting to crush an economic rival to its empire. This was true enough, and a welcome antidote to British hypocrisy about defending small nations, but neglected to mention that Germany was no less piratical in its own quest for empire and profit. Connolly went so far as to tell a socialist meeting on 4 October that ‘the German nation is fighting a necessary fight for the saving of civilisation in Europe’.

All of this was calculated to counter Britain’s justification for the war, of course, to deny her recruits and to undermine her war effort. The Defence of the Realm Act meant that there was a law against this kind of thing, and patriotic opinion in London was outraged. John Bull attacked the slogan beneath the Irish Worker’s masthead on 14 November, while under the impression that Larkin was to blame for it. The Times joined the fray ten days later: ‘In any other country in the world these disloyal journals would have been suppressed long ago’. The censor blocked Connolly’s editorial for 5 December (although the slogan still featured on the front page), and then the Irish Worker was suppressed altogether as part of a general crackdown on rebel papers.

But Liberty Hall still proclaimed non-allegiance to king or kaiser. A letter to the Irish Times on 10 December 1914 bemoaned the continuing presence of the ‘disloyal placard’, citing the danger posed by its close proximity to the Custom House, a government institution. At 2am on Sunday 19 December, 60 policemen with British army officers arrived with long ladders, removed the banner and fixed a notice to the door of Liberty Hall saying that it had been taken by military order. Presumably it was brought to Dublin Castle, but no trace of it has survived.

Connolly had the last word, however. For two months he managed to edit a successor paper, The Worker, printed by comrades in Scotland and smuggled to Dublin between sheets of glass. In the first issue on 26 December he wrote:

‘For the past two months the front of Liberty Hall has been decorated with a long painted linen sign bearing the words: “We Serve Neither King nor Kaiser”.

This sign was the first thing that caught the eye of the poor recruits landing from the boats at the North Wall, or being brought around from the Great Northern Railway. But it is gone! Captured by the All Lies: Alas!!!’

He described the enemy’s surprise pre-dawn raid on the banner and pointed out that photos of it on the front of the building could still be ordered from Liberty Hall. It is worth noting that this report drops the words ‘But Ireland!’ from the slogan. The addition and omission of them may suggest some second thoughts, a mark of the political tensions pulling Connolly to and fro as the war progressed.

He had many things to say about the war. In a time of unprecedented strain and difficulty, some of them were confused and contradictory, but all pointed clearly away from the obscenity of thousands slaughtered for the sake of the British Empire. ‘We Serve Neither King nor Kaiser (But Ireland!)’ was just one of the things he said on the subject, but it is far and away the most important. Nothing else was nearly as prominent or effective, and his personal pride in this propaganda coup is evident in how he handled the unveiling, publicising and ultimate suppression of the slogan.

BANNER NOT THERE AT EASTER 1916

In The Irish rebellion of 1916, published in New York only months after the Rising, Maurice Joy wrote that Connolly’s banner ‘remained in all its boldness’ even after Liberty Hall was shelled in Easter Week. The inaccuracy was repeated in Iris Murdoch’s The red and the green (1965), which has ‘the dripping banner’ on the building on Easter Sunday 1916. In another novel, Redemption by Leon Uris (1995), it is still up the day after. Roddy Doyle’s A star called Henry (1999) avoids that mistake, as its protagonist thinks back to the slogan while occupying the GPO with the Citizen Army. The narrative exposition here is slightly excessive, but Henry’s proposed amendment is interesting, to say the least:

‘We Serve Neither King Nor Kaiser. So said the message on the banner that had hung across the front of Liberty Hall, headquarters of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. If I’d had my way, Or Anyone Else would have been added, instead of But Ireland. I didn’t give a shite about Ireland.’

Aindrias Ó Cathasaigh has edited James Connolly’s The lost writings (Pluto Press, 1997) and is the author of An Modh Conghaileach (Coiscéim, 1996).

Further reading

R. Doyle, A star called Henry (London, 1999).

M. Joy, The Irish rebellion of 1916 (New York, 1916).

J.L. Motley, Rise of the Dutch Republic (3 vols) (New York, 1856).

P. Ó Cathasaigh [Seán O’Casey], Story of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin/London, 1919).