Some months ago Taoiseach Enda Kenny declared before President Obama and the world that the real wealth of Ireland was our history, our island story passed on from one generation to the next. It has sustained us in the past and will carry us on into a more prosperous future. And yet it is his government which is now about to threaten the very existence of history in our schools. The Minister for Education, Ruaidhrí Quinn, as part of his agenda to improve literacy and numeracy, has declared that the number of subjects that an individual student can take for the Junior Certificate examination will be limited to eight. These must include Irish, English and maths. Of the remaining five, most students will want to include a language and a science subject so as to leave their third-level options open. That leaves history, geography, music, art, domestic science, second languages, religion, business, economics, etc. all scrabbling for the remaining three places in each student’s programme. The minister will, of course, point out that students are free to choose history, but since it has few direct career implications ambitious parents and school principals will inevitably press the case for more utilitarian subjects in the examinable eight. And while the minister will say that schools can offer small modules of history, anyone familiar with the Irish education scene knows that that which is not examined is not valued and therefore not included in the timetable. The result is ‘goodbye history’, and probably some of the other subjects as well. One of the strengths of Irish education—the wide range of subjects studied by students in second-level schools—will be gone forever. And if history vanishes from the junior cycle of schools, how many will there be studying it at senior level?

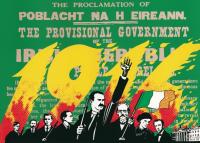

In a journal like this it is hardly necessary to make the case for retaining history. By definition, those who buy something called History Ireland must be interested in the subject. We value history as a way of understanding ourselves and where we come from. But will future generations be able to share this understanding? With a decade of commemorations coming up, are we about to produce a generation of historically illiterate young people, unable to set these events in context and liable to be excessively influenced by those who wish to use these anniversaries for their own purposes? Back in the early years of the state that was how history was taught. Nationalist myths went largely unexamined in the schools until the 1960s. We saw the results of that in 30 years of needless ‘armed struggle’. Better history and better history-teaching played a part in deconstructing the myths of the past from which some of this violence drew its inspiration. Do we want to risk allowing the myths to grow again?But school history is not just important for correcting nationalist myths. A person without some knowledge of the broad sweep of history is not properly educated. The current Junior Certificate programme allows students to know something about the Romans and the Normans, to have an idea about when Europeans reached America or when Martin Luther issued his challenge to the pope, to learn who painted the Mona Lisa or built the first factory, to understand the reasons for mourning the victims of the Irish famine and the Jewish holocaust. This history—the history of our world and our place in it—is our children’s heritage. Is the minister about to deprive them of it? But these are the arguments of the historically committed. There are also more general educational values to history. It gives students a sense of the past and their place in it. Without some study of history how does a young person understand the context out of which the present has grown? The popularity of ‘heritage’, whether in programmes like Who do you think you are? or in the search for family history, shows the deep need there is in people to understand themselves and their past. Students feel this too and need a study of the broader sweep of history to develop an understanding of the context out of which they come. The minister seems to think that by reducing the width of the Junior Certificate examination system he will provide more space for the improvement of students’ literacy and numeracy. Since history involves considerable amounts of reading, it is difficult to see how dropping it could increase the time available for developing reading skills. Numeracy too has its place in history. Understanding and manipulating dates involve sequencing numbers, and there is evidence that developing an understanding of sequence is important in a student’s development of mathematical understanding. So is understanding causation, and that is one of the central skills of history. The quality of Irish education has been much debated in recent months. This debate was sparked by the Pisa report, which showed an apparent slippage in standards of literacy and numeracy, though there is no evidence that those writing this report took on board the fact that in the period covered schools were also dealing with large numbers of foreign nationals for whom English was a second language and with integrating students with special needs into mainstream education. A recurring theme in this debate is the excessive reliance on rote learning; where Junior Certificate history is concerned, there is a good deal of validity in this criticism. But the critics are looking in the wrong place when they blame schools, teachers and the examination system as a whole. The real villain, at least where history is concerned, is the Junior Certificate examination paper. It is really bad. Questions ask for little snippets of information, detached from any context. Whole questions can be answered using memory alone. The skills of history, so clearly set out in the introduction to the syllabus, are not examined. Students hoping to do well do not have to demonstrate whether they have acquired these skills, and teachers have no need to teach them. Instead, for that all-important examination success, both pupil and teacher must be sure that ‘the facts’ have been learnt off by heart. Why is this? One reason is the policy of the Department of Education, which separates curriculum construction from the process of examination design. Committees work hard to come up with a good statement of aims and a well-balanced curriculum that is intended to develop the skills of history. They then have no input into how it is examined or whether the examination that emerges will test those aims and skills.

This is where reform should begin and where it is badly needed. A more searching examination paper—one that really tested the ability of students to analyse, criticise, sequence and contextualise—would go a long way towards overcoming the current criticisms of school history at Junior cycle. Of course, such a paper will be difficult to design and to mark, but the effort will be worthwhile. As the results of the Project Maths experiment seem to show, students can handle exam papers that ask them to think, not merely to remember. If this is done in history too the minister could leave behind a record of genuine reform instead of what at present seems his more likely legacy—an education system devoid of history and generations of historically illiterate young people. HI

Elma Collins is a former teacher and author of history textbooks.