The Treaty of Trianon, signed on 4 June 1920 between the ‘Principal Allied and Associated Powers’ and Hungary, was part of the far-reaching arrangements agreed upon at the Paris Peace Conference for the breaking up of the Habsburg empire after its defeat alongside imperial Germany in the First World War. It followed the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (10 September 1919), which limited a newly created republic of Austria to most of Cisleithania’s German-speaking provinces (not including the Sudetenland and South Tyrol) and recognised the independence of Hungary and other ‘successor states’—Poland, the Czecho-Slovak state and the Serb-Croat-Slovene state (which would evolve into Yugoslavia). Just as the previously signed Treaty of Versailles (28 June 1919) was widely denounced in Weimar Germany and the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (27 November 1919) was deplored by Bulgarians as their ‘second national catastrophe’ (preceded in popular memory by the débâcle in the Second Balkan War of 1913), Trianon would be regarded in Hungary as a national humiliation, its revived memory still considered today a burning issue for nationalists.

Summoned late to Versailles

After the war, Romanian, Czech and Serbian military forces availed of Hungarian demobilisation to occupy swathes of territories over which Hungary claimed sovereignty, while a national committee in Alba Iulia declared the annexation of Transylvania to Romania (1 December 1918). Unable to sustain territorial integrity in the face of growing concerns that temporary occupation zones would determine Hungary’s borders, Károlyi’s government collapsed and a communist takeover established a Hungarian Republic of Soviets (21 March 1919), effectively headed by Béla Kun. The Hungarian Red Army opened an offensive against the occupiers and, following initial success in northern territories, proclaimed a short-lived Slovak Soviet Republic (16 June). Enfeebled by continued economic blockade and having suffered military defeat at the hands of the French-sponsored Romanian army, the communist government soon collapsed (1 August) and Budapest was occupied by Romanian troops (3 August). Conservative counter-revolutionary parties, bolstered by foreign support, then seized control, with a right-wing ‘National Army’ under Admiral Miklós Horthy entering Budapest the day it was evacuated by the Romanians (16 November 1919). Owing to these precarious circumstances, Hungary was only summoned to the peace conference in December 1919.

By the time the Hungarian representatives arrived in Paris (7 January 1920), a year had passed since the conference first convened and the major decisions had already been made. The delegation was headed by the seasoned parliamentarian Count Albert Apponyi, who as minister for education during the Dual Monarchy had been instrumental in promoting a policy of Magyarisation, which fomented resentment towards Hungarian rule amongst ethnic minorities (his 1907 Education Act, in the words of A.J.P. Taylor, ‘deprived the nationalities even of their private schools’). Also included were two scions of Hungarian-Transylvanian nobility, Count István Bethlen and the geographer Count Pál Teleki, who were to assume key roles in Horthy’s administration. Their advocacy of boundaries based on ‘historical principles’ was jarringly out of tune with the prevalent Wilsonian discourse of the rights of small nations to self-determination. Point 10 of Wilson’s ‘Fourteen Points’ address to Congress on 8 January 1918 had specifically stated that ‘the peoples of Austria-Hungary . . . should be accorded the freest opportunity of autonomous development’. In a communication to Vienna on 18 October 1918, the US president updated his stance and stated that he was ‘no longer at liberty to accept the mere “autonomy” of these peoples’.

Signing the treaty

Without prior consultation, the Hungarian delegation was presented with a fait accompli—a lengthy document of 364 articles, divided into fourteen parts. The delegates found its contents intolerable to nationalist sensibilities, in particular Part II, ‘Frontiers of Hungary’ (articles 27 to 35), which stipulated that the kingdom of Hungary was to lose approximately 70% of its former territory and, according to their reckoning, almost a third of its ethnic Hungarian population (3.3 million out of 10.7 million) to six neighbouring countries (Romania, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Yugoslavia, Poland and Italy). John Maynard Keynes’s The economic consequences of the peace, published that year, called attention to the devastating ramifications of Versailles for Germany. The Hungarian economy—which, in addition to payment of reparations, lost access to the lion’s share of its resources, had its transport network broken up and suffered the withdrawal of capital investment from Vienna—was dealt an even more exacting blow. In the eyes of the Hungarians this was a diktat. It was evident to them that the terms must be accepted, yet it was feared that to append one’s name to the document would amount to political suicide. Apponyi and his delegation resigned and Teleki, who had meanwhile been appointed foreign minister in a new government formed in March, was reluctant to accept the responsibility. Finally, two inconsequential figures (Minister for Welfare Ákos Benárd and Plenipotentiary Ambassador Alfréd Drasche Lázár) undertook to sign the treaty at the date and time determined by the Allied Powers.

Without prior consultation, the Hungarian delegation was presented with a fait accompli—a lengthy document of 364 articles, divided into fourteen parts. The delegates found its contents intolerable to nationalist sensibilities, in particular Part II, ‘Frontiers of Hungary’ (articles 27 to 35), which stipulated that the kingdom of Hungary was to lose approximately 70% of its former territory and, according to their reckoning, almost a third of its ethnic Hungarian population (3.3 million out of 10.7 million) to six neighbouring countries (Romania, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Yugoslavia, Poland and Italy). John Maynard Keynes’s The economic consequences of the peace, published that year, called attention to the devastating ramifications of Versailles for Germany. The Hungarian economy—which, in addition to payment of reparations, lost access to the lion’s share of its resources, had its transport network broken up and suffered the withdrawal of capital investment from Vienna—was dealt an even more exacting blow. In the eyes of the Hungarians this was a diktat. It was evident to them that the terms must be accepted, yet it was feared that to append one’s name to the document would amount to political suicide. Apponyi and his delegation resigned and Teleki, who had meanwhile been appointed foreign minister in a new government formed in March, was reluctant to accept the responsibility. Finally, two inconsequential figures (Minister for Welfare Ákos Benárd and Plenipotentiary Ambassador Alfréd Drasche Lázár) undertook to sign the treaty at the date and time determined by the Allied Powers.

Back in Hungary, a day of mourning was proclaimed. Schools, offices and shops closed down. The press printed the news within black borders and flags were lowered to half-mast. Special religious services were held and all church bells in the capital tolled. Streetcars and trains observed a five-minute halt of service. In the streets of Budapest, masses of protesters wearing black ribbons and national emblems gathered to demonstrate. At the National Assembly, the speaker of the House, István Rakovszky, declared that the treaty ‘contained impossibilities, both from the moral and the material points of view, which make it unrealizable’. The plight of Hungarian communities that were forceably torn away from their homeland and often subjected to discrimination aroused heartfelt sympathy among their compatriots. Although their grievances would not disappear, these communities were obliged to accommodate themselves pragmatically to their new status. In contrast, independent Hungary’s dogged refusal to come to terms with the post-Trianon reality constructed, through embracement of irredentism, a lasting collective trauma.

‘Magyar Golgotha’

In nationalist myth-history, Trianon was located within a deep memory of catastrophic defeats, including such symbolic calamities as the overrunning of the country by Tartars after the Battle of Muhi (1241) and the rout of its aristocracy by the Ottomans at Mohács (1526). Interpreted through a quasi-Christian meta-narrative, these episodes were constructed as a cycle of victimhood, resembling the Passion of Christ (each one considered a ‘Magyar Golgotha’), which entailed a promise of national resurrection. In popular perception (proved mostly false by archival diplomatic documents), the harshness of the Trianon Treaty was attributed to the anti-Hungarian bias of the French, who were cast in the role played by ‘perfidious Albion’ in Irish nationalist history, with Clemenceau as a stand-in for a wily Lloyd George. Politicians and journalists latched on to supportive statements issued by such outside sympathisers as the British newspaper tycoon Lord Rothermere, who published in the Daily Mail ‘Hungary’s Place in the Sun’ (21 June 1927), to sustain demands for territorial revision encapsulated in the populist slogan ‘Justice for Hungary’.

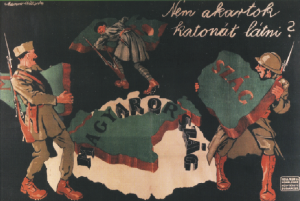

In the interwar years, irredentism was elevated to a national cult marked by annual memorials. Budapest’s centrally located Szabadség tér was fashioned into a pantheon for the cause, sporting allegorical monuments to the lost territories, laden in romantic imagery, as well as a ‘Statue of Hungarian Grief’. It was integrated into the school curriculum and children were taught to recite the ‘Hungarian Credo’ (the winning entry of a patriotic poetry competition in 1920): ‘I believe in one God, I believe in one Homeland, I believe in one divine eternal justice, I believe in the resurrection of Hungary. Amen’. Constantly promoted through popular print, in particular the conservative journal Magyar Szemle [Hungarian Review], irredentism permeated popular culture, becoming a staple of banal nationalism. The Trianon Museum in Várpalota (a present-day shrine of renewed irredentism) exhibits a dazzling array of memorabilia from the period: stamps, medallions, pins, badges, postcards, posters, tablecloths, household utensils, pencil cases and even board games. These were typically adorned with the truculent slogan ‘Nem, Nem, Soha!’ [No, No, Never].

The pursuit of revanchist policies was encouraged by the fascist dictator Mussolini. It would eventually drive Hungary into alliance with Nazi Germany, which allowed Horthy to reclaim some of the former Hungarian territories (in particular through the Vienna Awards of 1938 and 1940), though these gains would once more be lost following the defeat of the Axis in World War II.

The resurrection of memory

During the post-war years of socialist rule, mention of irredentism in Hungary was a taboo. In Marxist-Leninist analysis, Trianon was construed as the product of imperialism, serving bourgeois and landowner interests (an approach which underestimated the deeper implications of ethnic nationalism). In order to prevent tensions within the Eastern Bloc, its discussion in public was prohibited and all expressions of irredentist commemoration banned. The topic would, however, resurface after the collapse of communism. In 1990 Hungary’s first democratically elected prime minister, József Antall, announced that he would represent ‘in spirit’ 15 million Hungarians (which, at a time when the country’s population stood at 10.38 million, was an obvious reference to those residing beyond the state’s borders).

Initial post-communist references to Trianon, tainted by associations with ultra-nationalism and anti-Semitism, were guarded and mostly shunned by mainstream politicians. Recently, with the rise of a rejuvenated right wing, the floodgates have opened. In particular, since the 90th anniversary in 2010, local monuments to Trianon have mushroomed in towns and villages throughout Hungary. In that same year the ruling Fidesz conservative party backpedalled on its previous objections and declared 4 June—the anniversary of the signing of the treaty—a ‘National Day of Unity’. Ceremonies marking Trianon are now held nationwide, some of which offer a platform to such far-right organisations as the openly racist Sixty-Four Counties Youth Movement.

At a ground level, this new-found enthusiasm is propagated through various official and unofficial channels. Signposts list traditional Hungarian place-names, which have persisted in vernacular use (so that, for example, Bratislava appears as Pozsony or Cluj as Kolozsvár). Duna TV broadcasts to the wider Hungarian community, transcending state borders in its patriotic programming. The controversial Hungarian-Transylvanian writers Albert Wass, DezsŻ Szabó and József NyirŻ (all with dubious records from the fascist era) have been rehabilitated and their writings added to the high school curriculum. Alongside an assortment of xenophobic pulp literature peddled by street vendors, ubiquitous stickers on car bumpers depict maps of pre-Trianon Hungary draped in red and white ‘Árpád stripes’ or embellished with other nationalist iconography. Irredentist aspirations, however, are incongruous with membership of the European Union (which Hungary joined in May 2004), and renegotiation of borders is not on any political agenda. Moreover, the fanning of populist sentiments precludes constructive dialogue on reformulating regional policies to actually improve the rights of minorities.

The road not taken

In its day, Arthur Griffith’s famous The resurrection of Hungary: a parallel for Ireland (1904) was, in the words of Michael Laffan, ‘for many years the bible of the Sinn Féin party’, though in terms of factual comparative history its value is limited. In contrast, if contemplating counterfactuals and taking into account the politics of memory, then Hungarian revived preoccupation with Trianon can offer a sobering perspective on Irish nationalist opposition to partition. In the Good Friday Agreement, the governments of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland agreed to ‘recognise the legitimacy of whatever choice is freely exercised by a majority of the people of Northern Ireland with regard to its status’, while promising ‘full respect for, and equality of, civil, political, social and cultural rights, of freedom from discrimination for all citizens’. This democratic formula, in conjunction with the amendment of the territorial claim in Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish constitution, offered a way to peacefully circumvent, if not fully resolve, the quandaries of a legacy of partition, without succumbing to the deceptions of renewed irredentism. HI

Guy Beiner is a senior lecturer in modern history in Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and was recently a Government of Hungary visiting research fellow at the Central European University.

Further reading

R. Pearson, ‘Hungary: a state truncated, a nation dismembered’, in S. Dunn and T.G. Fraser (eds), Europe and ethnicity: the First World War and contemporary ethnic conflict (London and New York, 1996), 85–105.

I. Romsics, The dismantling of historic Hungary: the peace treaty of Trianon, 1920 (Wayne NJ, 2002).

S.B. Várdy, ‘The Trianon syndrome in today’s Hungary’, Hungarian Studies Review 24 (1–2) (1997), 73–9.

M. Zeidler, Ideas on territorial revision in Hungary, 1920–1945 (Wayne NJ, 2007).